Clinical observations indicate that autistics may have “reduced motivation to seek social interaction, yet a heightened motivation to expend effort in the pursuit of certain non-social stimuli.”[1]Adults with autism spectrum disorders exhibit decreased sensitivity to reward parameters when making effort-based decisions

In other words, we tend to prefer doing work or pursuing interests over socializing. But also, we expend effort on our pursuits for lesser rewards,[2]Adults with autism spectrum disorders exhibit decreased sensitivity to reward parameters when making effort-based decisions which is a double-edged sword; we are more likely to pursue interests despite fewer rewards, but because of this we make ourselves vulnerable to be taken advantage of. Like researchers from a 2012 study state:[3]Adults with autism spectrum disorders exhibit decreased sensitivity to reward parameters when making effort-based decisions

Clinical observation suggests that individuals with ASD

may show dysregulated reward-based effort.

Repetitive behaviors

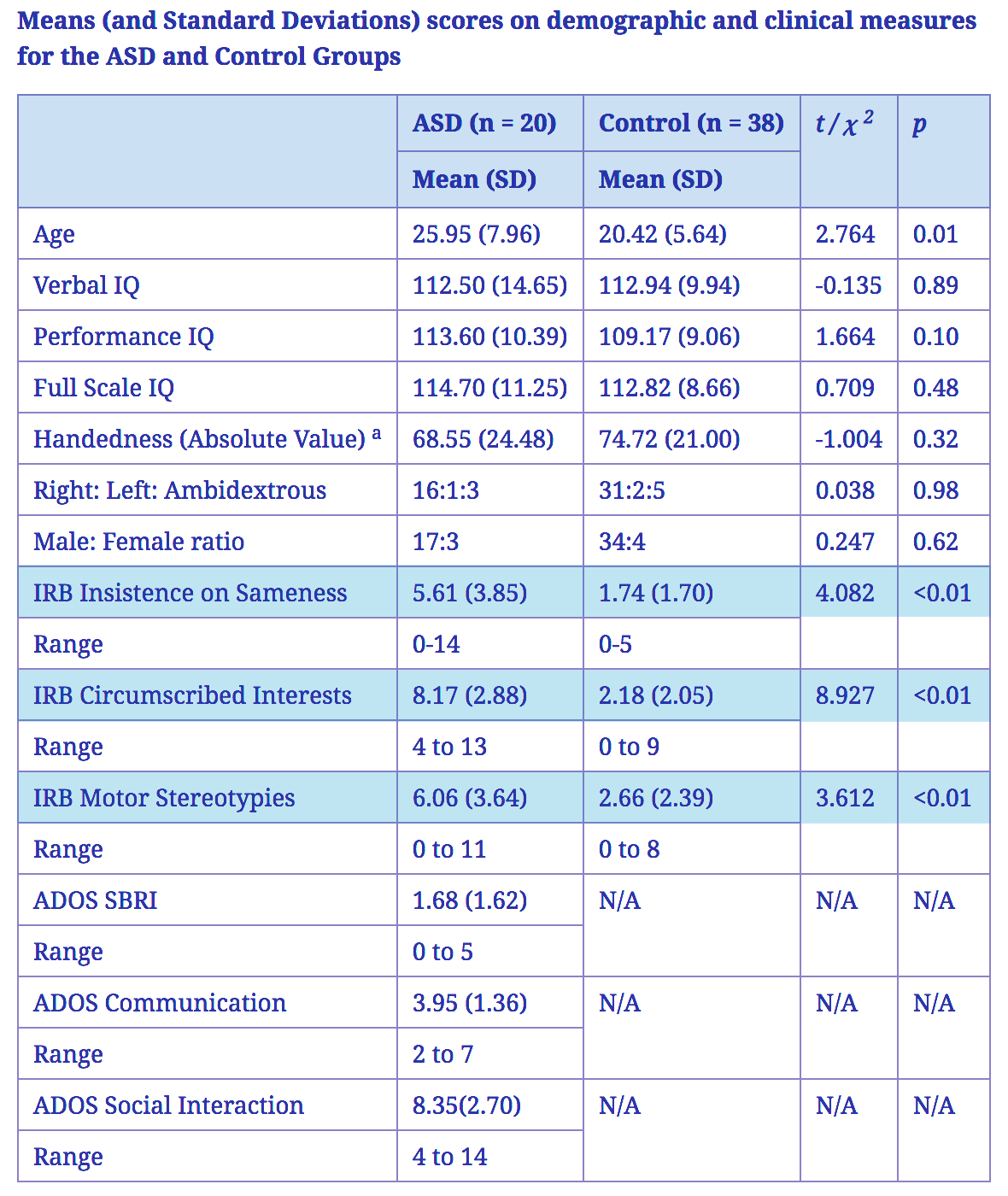

In the table below from a study from 2012,[4]Adults with autism spectrum disorders exhibit decreased sensitivity to reward parameters when making effort-based decisions you can see how autistics (20) compare to non-autistics (38) on a myriad of factors, including Insistence on Sameness, Circumscribed Interests, and Motor Stereotypies on the Interview for Repetitive Behaviors (IRB)—a diagnostic instrument used to assess autism on the basis of willingness and desire to do repetitive tasks (devised by James W. Bodfish).[5]Inventory for Repetitive Behaviors (IRB) (Bodfish, 2003) [Unpublished Rating Scale, University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, Western Carolina Center Research Reports]

We will get back to the table in a moment. First, let me explain what the three highlighted factors mean:

Insistence on sameness

The desire for sameness, and a tendency to do—or think about—the same things repeatedly, as if doing so were a comfort or a compulsion.[6]Insistence on sameness | Interactive Autism Network

The insistence on sameness also comes with resistance to change, or a proneness to dysregulate when a routine is interrupted.

Circumscribed interests

An intense focus on and/or interest in certain objects or topics (e.g. watching the circular movements of a washing machine or memorizing numbers).[7]Phenomenology and measurement of circumscribed interests in autism spectrum disorders

Motor stereotypies

Common, repetitive, rhythmic movements (e.g. stimming) with typical onset in early childhood.[8]Motor Stereotypies: A Pathophysiological Review

Pursuing interests

Note in the table above that autistics score significantly higher on these three factors than neurotypicals.

Motor stereotypies emerge as a way of stress relief or enhancement of certain sensory experiences. While this often presents as stimming, it can also be used in pursuit of interests, or indeed shape those very interests in the first place. For example, the need for repetitive, rhythmic movements may influence one to get into music, and perhaps in particular drumming.

Circumscribed interests refer to our intense focus on the things that interest us. As a result, a lot of us are autodidacts, and tend to be experts of sorts in particular fields or topics, since we tend to dig deep into the subjects we love, and try to know everything there is to know about the topic.

Insistence on sameness is a relevant factor because, in combination with decreased social motivation,* autistics are prone to self-study or practice as they emerge themselves in topics of interest. The insistence on sameness can thus be highly conducive to one’s pursuit of interests, as well as adhering to a routine regarding work.

- Read more about social motivation in autism here: My social life as an autistic person

Hard task choices & reward probability

Not only do we tend to be driven by the things we love (at the expense of social motivation), but we are also more willing to perform certain tasks for lesser rewards.

In the graph below you can see how the probability of acquiring a reward relates to the number of hard task choices being made, where you can see that autistic people choose to do more hard task choices, but also choose to do more despite a much lower reward probability compared to controls.[9]Adults with autism spectrum disorders exhibit decreased sensitivity to reward parameters when making effort-based decisions

So as you can see, we are more inclined than non-autistics to perform difficult tasks despite lower rewards.

Hard task choices & reward magnitude

In the graph below you can see how the reward magnitude relates to the number of hard task choices made.[10]Adults with autism spectrum disorders exhibit decreased sensitivity to reward parameters when making effort-based decisions

As you can see, autistic people make a lot of hard task choices despite very small rewards, and only for large rewards do non-autistics approach autistics in their efforts—yet still fall short.

Hard task choices & IRB

In the graph below you see how the Interview for Repetitive Behaviors (IRB) correlates with the number of hard task choices made. The IRB was based on restricted and repetitive, stereotyped interests and behaviors.

A couple of things can be observed from this graph:

Interview for Repetitive Behaviors

- Most neurotypicals score within 35.71% of the total extent of repetitive behaviors observed in this test (many in fact within 7.14%).

- Of the 16 autistic participants, the lowest score on the IRB was 4 out of 14, which is close to the general maximum neurotypicals score (5 out of 14, with one outlier scoring 9 out of 14). In other words, some of the most repetition-driven neurotypicals are similar to autistic people with the mildest presentation of repetitive behaviors.

- 81.25% of the autistic participants scored 8 or higher, while 1 out of 34 neurotypical participants (2.94%) scored 8 or higher (9).

Hard task choices

- As you can see, a lot of neurotypicals barely perform any repetitive tasks at all. “I did this before—I’m going home now” might ironically be perceived as an autistic statement, but it’s actually neurotypicals that would have this mentality.

- Not only do autistic people perform much more repetitive tasks, but as you can see from the scatterplot, none of them chose to do hard task choices less than 30% of the time, while 26.47% of neurotypicals chose to do hard task choices up to 30% of the time.

- Of the neurotypicals, only 11.76% chose to do hard task choices 70% of the time or more often. Of the autistic people, 50% chose to do hard task choices for 70% of the time or more often.

- There are 4 people who chose to do more repetitive tasks and make more hard task choices than any neurotypical. So they are the most repetitive, but also the hardest workers.

Conclusion

While neurotypicals acquire dopamine from social situations[11]Oxytocin, motivation and the role of dopamine[12]Dopaminergic Dynamics Contributing to Social Behavior—and mouse models even show that social isolation increases the drive to seek out social behavior.[13]Surprise role for dopamine in social interplay—they experience diminished pleasure from repeated exposure to foods, things, and tasks.

Autistics on the other hand are largely denied dopamine in social situations. Instead, our brains continue to reward us intrinsically for doing work and/or pursuing our interests—regardless of repetition. So it’s not that we don’t get bored by repetition necessarily, but we tend to pursue these activities over socializing, we derive more pleasure from them, and we are more prone to expend effort despite lower rewards.

The autism slogan for work ethic might be something along the lines of:

Works hard for little—requires no time off.

If given time off, will work some more…

Such has been our experience, in any case—provided we love the work we do.

NB: this is no excuse for employers to overwork autistic employees at the minimum salary. Rather, it is a testament to our work ethic. Treat us—and pay us—well, and we can do wondrous things.

Fair warning to autistics: Don’t undersell yourself or do a lot of work/favors without ever getting anything back for it. I have done it many times myself, where I invest time in helping others but don’t ever get the same time investment in return. It’s not like I always expect something in return, but when you give a lot and never get anything back, you should ask yourself if your time isn’t better spent on personal pursuits than (so many) favors for others.

Comments

Let us know what you think!