Autism is not a static concept, nor is the way that autism is perceived static. As the concept of autism evolved over the years along with—and informed by—our increasing understanding of the condition and its various manifestations, naturally the autism classifications—the terminology used to refer to the condition(s)—evolved as well.

While researching the history of autism classifications I stumbled upon some researchers and their work I never read about before, so I hope our timeline of autism classifications offers some information that is new to you too—albeit the information itself is pretty old, going back even to 1887.

Also, there may or may not be a visualization of the timeline at the end of this post…

1887

Developmental retardation

The British physician John Langdon Down (1828–1896) described savant syndrome in his 1887 lecture,[1]Review of: On some of the mental affections of childhood and youth (Churchill, 1887) but also described a subgroup of children with “mental retardation” that didn’t show many of the hallmarks of more typical mental retardation, and called it developmental retardation. He described what seem to be cases of both early-onset and late-onset (regressive) autism, which today would be considered ASD level 3.[2]Dr. Down and “developmental disorders” (Treffert, 2006)

Interestingly, 93 years after he chose the term ‘developmental’, the term ‘developmental disorders’ was included in the DSM-III (1980), which included autistic disorder.[3]The savant syndrome: an extraordinary condition. A synopsis: past, present, future (Treffert, 2009)

- Read a digitized publication based on John Langdon Down’s 1887 lecture here: On some of the mental affections of childhood and youth

1908

Autism

The word autism (Greek autos, meaning self) was first used by Swiss psychiatrist and eugenicist Eugen Bleuler (1857–1939) to describe schizophrenic patients who were especially withdrawn into themselves. Bleuler describes in his paper entitled Die prognose der Dementia praecox (The prognosis of dementia praecox) from 1908:

The autistic withdrawal of the patient to his fantasies,

against which any influence from outside becomes an intolerable disturbance. This seems to be the most important factor.

In severe cases it by itself can produce negativism.[4]Eugen Bleuler’s Concepts of Psychopathology (Kuhn, 2004)

In a footnote of his 1910 paper entitled Zur Theorie des schizophrenen Negativismus (The Theory of Schizophrenic Negativism), Bleuler wrote:

What I understand as autism is about the same as

Freud’s autoerotism, but I prefer to avoid using this expression, because everybody who does not know Freud’s writings

exactly misunderstands it.[5]Eugen Bleuler’s Concepts of Psychopathology (Kuhn, 2004)

1926

Schizoid personality disorder

The Soviet child psychiatrist Grunya Sukhareva (1891–1981) wrote a paper entitled Die schizoiden Psychopathien im Kindesalter (The schizoid psychopathies in childhood) in 1926, in which she described boys with what she called schizoid personality disorder.[6]The first account of the syndrome Asperger described? Translation of a paper entitled “Die schizoiden Psychopathien im Kindesalter” (Ssucharewa & Wolff, 1996)

Not a lot of people have heard of her work,[7]Tribute to Grunya Efimovna Sukhareva, the woman who first described infantile autism (Posar & Visconti, 2017) but what she described was in fact indistinguishable from the condition that Hans Asperger described 18 years later.

1943

Autistic disturbance

Austrian-American child psychiatrist Leo Kanner (1894–1981) publishes a paper entitled Autistic Disturbances of Affective Contact in 1943, describing 11 children who were highly intelligent but displayed:[8]Autistic Disturbances of Affective Contact (Kanner, 1943)

- Difficulties in social interactions.

- Difficulty in adapting to changes in routines.

- Good memory.

- Sensitivity to stimuli (especially sound).

- Resistance and allergies to food.

- Good intellectual potential.

- Difficulties in spontaneous activity.

- Echolalia (the propensity to repeat words of the speaker).

He described these children as having:

A powerful desire for aloneness, and an

obsessive insistence on persistent sameness.[9]Autistic Disturbances of Affective Contact (Kanner, 1943)

1944

Early infantile autism

Leo Kanner later names the condition he described the year before as early infantile autism, in his 1944 paper Early infantile autism. Here is a quote from the abstract of the paper:

All were much obsessed by a desire for absolute sameness of routine and were much upset by change of any kind. It is noted that most of the children came from families of academic distinction. Nine of the 20 families were listed either in Who’s Who in America or American Men of Science or in both.

Whether or not the preoccupation of these persons with abstractions rather than with people is a characteristic that has become pathologically exaggerated in their descendents is uncertain.[10]Early infantile autism (Kanner, 1944)

1944

Autistic psychopathy

The Austrian pediatrician Hans Asperger (1906–1980) was long supposed to have been the first scientist to describe Asperger syndrome; in 1944 he published a paper entitled Die Autistischen Psychopathen im Kindesalter (Autistic Psychopathy in Childhood),[11]On the origins and diagnosis of asperger syndrome: a clinical, neuroimaging and genetic study (Wendt, 2004) in which he describes 4 boys with special talents, but also with:

A lack of empathy, little ability to form friendships, one-sided conversations, intense absorption in a special interest, and clumsy movements.[12]Asperger’s Syndrome: A Guide for Parents and Professionals (Attwood, 1998)

The term autistic psychopathy, by the way, has nothing to do with the term ‘psychopathy’ as we use it today, but rather it meant a ‘psychopathology’, or mental disorder. It is essentially a term for autism disorder—a term that is introduced in the DSM-III-R (1987).

1952

Childhood schizophrenia

In the DSM-I (1952), autism is categorized under childhood schizophrenia.

This classification was retained in the DSM-II (1968).

1980

Infantile autism

36 years after Leo Kanner’s introduction of the term ‘early infantile autism’, the term infantile autism was now listed in the DSM-III (1980), and officially separated from childhood schizophrenia.

Interestingly, the autism diagnosis in the DSM-III (1980) was much narrower than in the DSM-5 (2013), so many people that are considered on the autism spectrum today would not have qualified for an autism diagnosis in 1980.[13]The evolution of “autism”: Comparing DSM-III and DSM-5 | Cracking the Enigma

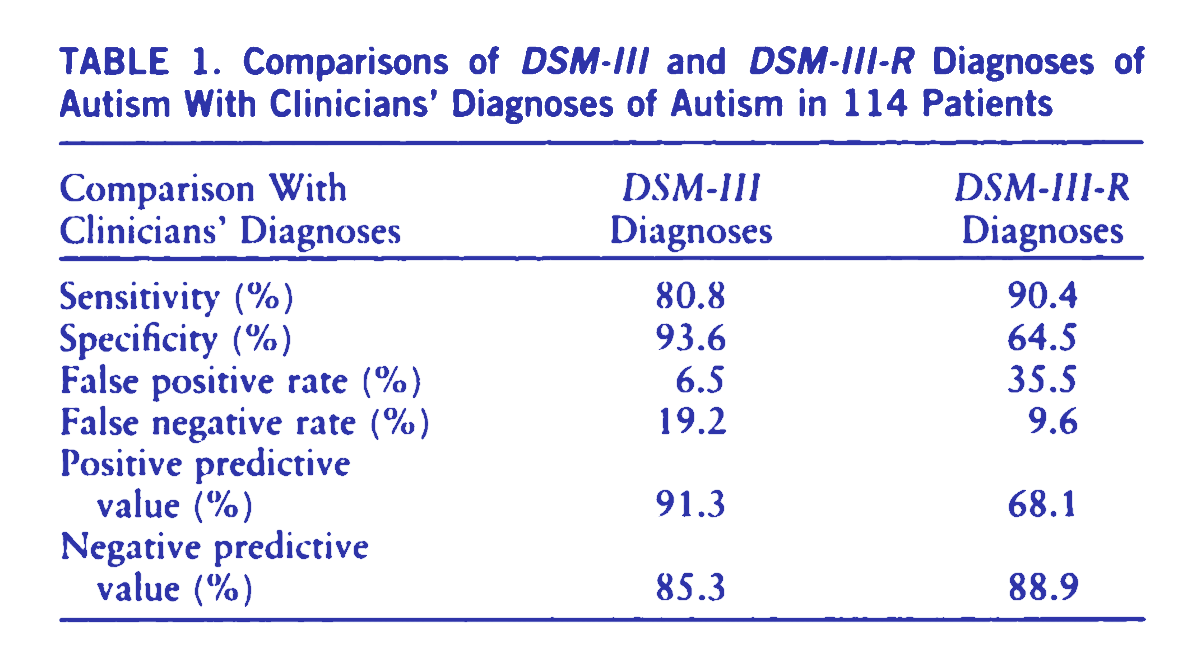

Even the DSM-III-R (1987) has a broader autism diagnosis, as you can see in the table below.[14]DSM-III and DSM-III-R diagnoses of autism (Volkmar et al., 1988)

With an increase in sensitivity and a decrease in specificity, the diagnostic scope is broadened, and more people are diagnosed with infantile autism. As a result of this broadening of the diagnostic criteria, more people that do not have autism mistakenly got an autism diagnosis, but on the other hand, fewer people that do have autism are excluded from an autism diagnosis.

1981

Asperger’s syndrome

English psychiatrist Lorna Wing (1928–2014) introduced the English-speaking medical world to the work of Hans Asperger in her 1981 paper Asperger’s syndrome: a clinical account.

She also introduced the term Asperger’s syndrome—after Hans Asperger and his research—which Hans Asperger originally referred to as ‘autistic psychopathy’. In her paper she writes:[15]Asperger’s syndrome: a clinical account (Wing, 1981)

The name he chose for this pattern was autistic psychopathy, using the latter word in the technical sense of an abnormality of personality. This has led to misunderstanding because of the popular tendency to equate psychopathy with sociopathic behaviour.

For this reason, the neutral term Asperger’s syndrome

is to be preferred and will be used here.

1987

Autism disorder

The term ‘infantile autism’ was replaced by the term autism disorder in the DSM-III-R (1987), a revised edition of the DSM-III (1980).

A checklist of diagnostic criteria was also included.

1993–1994

Asperger syndrome

Asperger syndrome was finally included in the ICD-10 (1993) and the DSM-IV (1994), 50 years after Hans Asperger described the condition, and 67 years after Grunya Sukhareva described the condition.

Lorna Wing’s influential article proposed the term Asperger syndrome resulting in this new clinical diagnosis being included in the diagnostic manuals. Grunya Sukhareva’s work would still not be known at this time (nor even today), or the condition might have been called Sukhareva syndrome.

Imagine that, being a Sukharie instead of an Aspie! Maybe not a good idea, as the expressions “Suckie!’ and “You Sukh!” are too easy to come up with as insults. Let’s not give our mortal enemies more ammunition.

1994

Pervasive developmental disorders

The DSM-IV (1994) introduced the umbrella term pervasive developmental disorders, which included:

- Asperger syndrome

- Autistic disorder

- Childhood disintegrative syndrome

- Rett’s disorder

- Pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS)

2013

Autism spectrum disorder

Autism spectrum disorder was added to the DSM-5 (2013) as an umbrella condition encompassing all previous separate autism-related diagnoses. Social (pragmatic) communication disorder (SCD) is introduced as a distinct diagnosis.

All subcategories and distinctions are generalized under the term autism spectrum disorder, and Asperger syndrome is no longer considered a separate condition, but a high-functioning form of autism.

2018

Asperger syndrome & high-functioning autism

Since 2013 research has still maintained some distinctions within the autism spectrum, and still used terms like ‘Asperger syndrome’ and ‘high-functioning autism.’ In fact, at the time of writing this article, Google Scholar gives 18,100 results when I search for papers with the term Asperger syndrome since 2014,[16]Google Scholar: Asperger syndrome (2014—) and 18,700 results for high-functioning autism.[17]Google Scholar: High-functioning autism (2014—) This in itself does not show the two conditions are distinct, but that both terms are (still) popular in the research literature.

But new research is also emerging that indicates differences between Asperger syndrome and high-functioning autism,[18]Subtyping the Autism Spectrum Disorder: Comparison of Children with High Functioning Autism and Asperger Syndrome (de Giambattista et al., 2018) which suggests some of the terminology the DSM abandoned in 2013 may have some utility. The term ‘high-functioning’ is questionable, but the correlations should not be ignored. It may prove useful to come up with different terminology to be able to talk about real distinctions between distinct presentations of autism, without necessarily implying anything about the level of functioning or support needs.

2000?

Autism spectrum condition

We don’t agree with everything that English clinical psychologist and professor of developmental psychopathology Simon Baron-Cohen (1958—) says, but we do praise him for using the term autism spectrum conditions (ASC) rather than autism spectrum disorders (ASD) in many of his papers, at least since 2000.[19]Linguistic processing in high-functioning adults with autism or Asperger’s syndrome. Is global coherence impaired? (Jolliffe & Baron-Cohen, 2000) ASC is a lot more neutral in language, which seems only proper considering autism is not characterized exclusively by deficits, and so to call our condition a disorder doesn’t really do it justice in my opinion. Even if we adhere to its definition, the negative language used does not do the perception of autism—and by extension how we ourselves are perceived—any good. Read more about the term ‘disorder’ and its consequences here:

Why is autism seen as a disorder?

While some other researchers use ASC as well, the term has not yet become common use. It was the unfamiliarity of the term and as such its low marketability that prevented us from calling our website Embrace ASC. But things may look a lot more positive, as the popularity of the term seems to be on the rise; Google Scholar gives:

- 6 search results of the term in 2000[20]Google Scholar: Autism spectrum condition (2000)

- 8 in 2005[21]Google Scholar: Autism spectrum condition (2005)

- 56 in 2010[22]Google Scholar: Autism spectrum condition (2010)

- 204 in 2015[23]Google Scholar: Autism spectrum condition (2015); and

- 262 in 2018 so far.[24]Google Scholar: Autism spectrum condition (2018)

Someone cynical might say this is an indication of an increase in political correctness, but I think—certainly hope—this is an indication that people are starting to acknowledge our advantages.

2019

What do you think?

What terminology do you find most appropriate to describe your condition? Let us know in the comments below.

By the way, who noticed the characters of Leo Kanner and Hans Asperger aging as you scrolled down?

Comments

Let us know what you think!