Asexuality seems fairly common among autistic people. So in this article, I will describe what asexuality entails, what identities are part of the ace spectrum, and how common asexuality in autism actually is. And as a bonus, I will talk a bit about how I relate to the ace spectrum and some new things I discovered about myself.

What is asexuality?

Asexuality is a sexual orientation or identity that is generally defined as a lack of sexual attraction to other people,[1]Asexual identity development and internalisation: a scoping review of quantitative and qualitative evidence (Kelleher, Murphy & Su, 2021) but is more broadly defined as either:[2]Defining Asexuality as a Sexual Identity: Lack/Little Sexual Attraction, Desire, Interest and Fantasies (Catri, 2021)

- A lack of sexual attraction to other people

- Little sexual attraction, desire, interest, or fantasies

Beyond this description, there is some debate as to what asexuality is exactly, and what its cause is. Is it a natural variation, or do certain events in one’s life trigger it? Van Houdenhove et al. notes that it’s easier to describe what asexuality is not, than what it is.[3]A Positive Approach Toward Asexuality: Some First Steps, But Still a Long Way to Go (Van Houdenhove, Enzlin & Gijs, 2017)

- Most researchers agree that asexuality is not a mental disorder, nor a symptom of one[4]Asexuality: What It Is and Why It Matters (Bogaert, 2015)[5]Asexuality: A Mixed-Methods Approach (Brotto et al., 2010)[6]How is asexuality different from hypoactive sexual desire disorder? (Hinderliter, 2011)[7]Asexuality: Classification and Characterization (Prause & Graham, 2007)[8]Asexuality: Few Facts, Many Questions (Van Houdenhove, T’Sjoen & Enzlin, 2013)

- They further conclude that asexuality is neither regarded as a sexual dysfunction nor a paraphilia[9]Asexuality: Sexual Orientation, Paraphilia, Sexual Dysfunction, or None of the Above? (Brotto & Yule, 2017)[10]A Positive Approach Toward Asexuality: Some First Steps, But Still a Long Way to Go (Van Houdenhove, Enzlin & Gijs, 2017)

- Some define asexuality as a sexual identity[11]There’s more to life than sex? Difference and commonality within the asexual community (Carrigan, 2011)[12]New Orientations: Asexuality and Its Implications for Theory and Practice (Cerankownski & Milks, 2010)[13]Coming to an Asexual Identity: Negotiating Identity, Negotiating Desire (Scherrer, 2008)

- While others define it as a sexual orientation[14]Toward a Conceptual Understanding of Asexuality (Bogaert, 2006)[15]Asexuality: What It Is and Why It Matters (Bogaert, 2015)[16]Asexuality: An Extreme Variant of Sexual Desire Disorder? (Brotto, Yule & Gorzalka, 2015)[17]Asexuality: Sexual Orientation, Paraphilia, Sexual Dysfunction, or None of the Above? (Brotto & Yule, 2017)[18]Theoretical issues in the study of asexuality (Chasin, 2011)[19]Asexuality: from pathology to identity and beyond (Gressgård, 2013)

Asexuality doesn’t necessarily mean a complete lack of a sex drive; it could just mean a lack of desire or a very low desire to act on sexual urges, or having sexual urges but lacking a drive to sexually engage with other people. In a 2016 Asexual Community Survey Report, 42% of participants rated their sex drive as 1 on a scale from 0 (non-existent) to 4 (very strong).[20]The 2016 asexual community survey summary report (Bauer et al., 2018)

Note also that being asexual doesn’t necessarily mean a lack of romantic attraction or desire for intimate and close relations that might include physical contact of some sort.[21]Are Autism Spectrum Disorder and Asexuality Connected? (Attanasio et al., 2022) Asexual people may or may not be aromantic.

The asexual spectrum

The asexual—or ace—community includes a spectrum of identities, including:

- Asexual: Someone who experiences no sexual attraction to others

- Gray-asexual/graysexual: Someone who experiences sexual attraction rarely or only under specific circumstances

- Demisexual: Someone who experiences sexual attraction only after forming an emotional bond

There is a lot more variance and nuance in the ace spectrum, however. Besides the three better-known categories defined above, the following are also part of the ace spectrum:[22]Ace and aro spectrum definitions | OU LGBTQ+ Society

- Abrosexual/ace flux: Someone whose experiences of sexual attraction fluctuate; they may go through periods of asexuality and periods of experiencing sexual attraction; and they may go through phases of weak or more intense sexual attraction

- Akoisexual: Someone who experiences sexual attraction to people but has no desire to have those feelings reciprocated; for some, if the attraction is reciprocated, their feelings may fade, and they will no longer be attracted to that person

- Fraysexual: Someone who initially experiences sexual attraction upon meeting someone, but this attraction fades after getting to know them

- Lith(o)sexual: Someone who doesn’t like to receive sexual contact, but who may be happy to give it

- Apothisexual: Someone who is not only asexual, but also sex-repulsed

- Cupiosexual: Someone who desires a sexual relationship, but does not experience sexual attraction

- Quoisexual: Someone who is unsure whether they experience sexual attraction, or is unsure about what sexual attraction is

Going through this list, I guess I’m technically abrosexual and demisexual? I probably won’t remember the former term, but it’s fascinating to see the different asexual identities and experiences, and to find out that some of them actually apply to me. I never identified as asexual, so it’s quite surprising to find out I’m somewhere on the ace spectrum. More so now than pre-transition.

Note also that there is both an asexual and aromantic spectrum that can intersect. If you’re interested in learning more about the different identities on the aromantic spectrum as well, have a look at the ace & aro list from the Oxford University LGBTQ+ Society:

Ace & aro spectrum definitions

My experience of asexuality

I will get to the prevalence of asexuality among autistics soon; but first, I would like to make the observation that my autistic loved ones and myself pretty much cover the asexual spectrum outlined above. Here is my description, as well as how my loved ones describe their sexual attraction and desire (posted with their permission):

Eva

I would describe myself as demisexual; I experience sexual desire and attraction, but my sexual attraction is mediated by an emotional bond. I couldn’t envision myself engaging with anyone sexually in a casual fashion, and I never understood the appeal of one-night stands.

Additionally, I’m trans, and since I started HRT at the end of 2021, my sex drive has plummeted from 100 to maybe 5, with the occasional fluctuation to 15 or so. So based on that, it seems I’m abrosexual now. Although I’m still interested in sex, I have a very low desire to act on what little sex drive I have left. So I guess I may have transitioned from being demisexual to demi/abrosexual—possibly even graysexual.

Natalie

Natalie, my wife, has described herself as pansexual, demisexual, and asexual. So I suppose technically she would be graysexual. She also adds that she is not sure if she is innately asexual or if it’s a trauma response due to being sexually abused as a child. It’s hard for her to have sex without her body feeling stiff and adverse, but she finds that she enjoys sex when she feels safe

J

One of my friends is attracted to the idea of sex, and experiences arousal and desire for sex. But they rarely experience arousal and desire toward specific individuals, and are unsure if they experience sexual attraction toward specific individuals or if it’s something more like ‘aesthetic attraction with sexual undertones’

H

One of my other friends describes herself as asexual, and will very rarely engage sexually with her partner. She only experiences ever sexual attraction (although unlikely and rarely) with someone she has a very close bond with, she resonates a bit with demisexuality.

She feels that the little sexual attraction she does have might not be the same as others’, which leads her to think ‘asexual’ is a better term for her experience than demisexual.

She might sometimes crave the endorphins released during sex and can acknowledge it makes her feel closer to her partner afterward, yet she doesn’t crave sexual activities themselves. She feels that any sexual urges come from a very biological place, rather than from an emotional one—or wherever it comes from for other people.

Attitudes towards sex

People on the ace spectrum can have different attitudes towards sex, from positive but low interest, to indifference, to outright aversion:[23]The Asexuality Spectrum: Understanding the Different Types of Asexual (Anwar, 2022) | TalkSpace

- Sex-favourable: While asexual people don’t experience sexual attraction per se, sex-favourable ace people generally have favorable feelings about sex, and some sex-favourable asexuals may choose to have a sexual relationship

- Sex-neutral: Sex-neutral asexual people generally feel indifferent to sexual activity; they don’t have any strong positive or negative feelings about sex, and may not really think about sex

- Sex-repulsed: Sex-repulsed asexual people are generally aversive to sex; to them, sex seems unpalatable or even disgusting and repulsive. Sex-repulsed asexual people may not condemn sexual activity as morally wrong, but they do find it to be extremely unpleasant

In the table below, you can see the potential attitudes towards sex of each asexual orientation/identity. Note, however, that these are approximations; your attitude towards sex may differ from what is listed below.

Asexual spectrum vs. attitudes towards sex

Prevalence

The prevalence of asexuality is estimated to be somewhere between 0.4%[24]Who reports absence of sexual attraction in Britain? Evidence from national probability surveys (Aicken, Mercer & Cassell, 2013)[25]The demography of asexuality (Bogaert, 2013)[26]Asexual Identity in a New Zealand National Sample: Demographics, Well-Being, and Health (Greaves et al., 2017) and 1%[27]Asexuality: prevalence and associated factors in a national probability sample (Bogaert, 2004)[28]Toward a Conceptual Understanding of Asexuality (Bogaert, 2006)[29]The demography of asexuality (Bogaert, 2013)[30]Patterns of Asexuality in the United States (Poston & Baumle, 2010) in the general population. Although other prevalence estimates are higher, such as a Finnish study reporting a lack of sexual attraction in up to 3.3% of women and 1.5% of men.[31]Finnish Women and Men Who Self-Report No Sexual Attraction in the Past 12 Months: Prevalence, Relationship Status, and Sexual Behavior History (Höglund et al., 2014)

In terms of the prevalence of asexuality among autistic people, a 2009 study found that approximately 33% of their sample appeared to be asexual. However, no data was presented on this; the paper states, “Anecdotally, about one third of the patients, male and female, had no interest in establishing a sexual relationship, and seemed asexual in their orientation.” They further state that some—mostly male—tried and failed to pursue sexual relationships.[32]Autism spectrum disorder grown up: a chart review of adult functioning (Marriage, Wolverton & Marriage, 2009) Celibacy or inability to pursue sexual relationships is obviously not the same as asexuality, but some may self-identify as asexual on account of a lack of sexual experiences.

A 2021 study on autistic people aged 21–72 (with a medium of 34 years) showed more nuanced and interesting findings:[33]Beyond the Label: Asexual Identity Among Individuals on the High-Functioning Autism Spectrum (Ronis et al., 2021)

- 5.1% of participants self-identified as asexual; however,

- 19.2% of participants could be classified as asexual based on their scores on the Asexuality Identification Scale (AIS);[34]A Validated Measure of No Sexual Attraction: The Asexuality Identification Scale (Yule, Brotto & Gorzalka, 2015) however, the authors caution against considering those people asexual in the absence of them self-identifying as such; however,

- 2.3% of participants who reported no sexual attraction did not identify as asexual, which suggests that there may be considerable diversity in the expressions of asexual attraction

Asexuality in autistics vs. neurotypicals

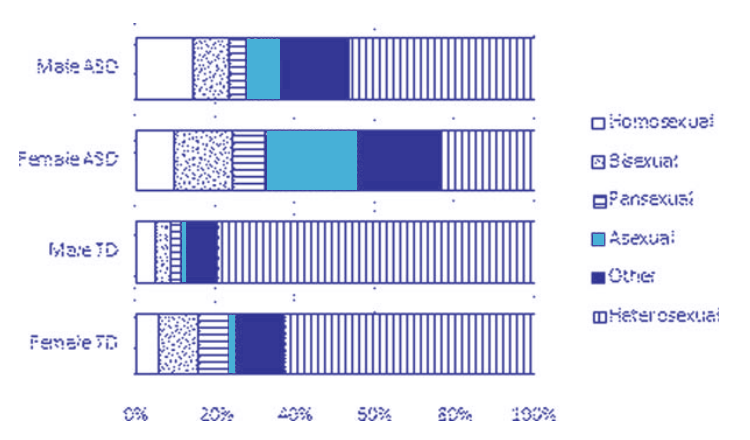

A 2017 study that looked into sexual orientations in autistic people unfortunately didn’t explicitly state prevalence rates, but it included a diagram showing the differences in sexual orientations of autistic people vs. neurotypical people.[35]Sexual Orientation in Autism Spectrum Disorder (George & Stokes, 2017) Granted, it’s horrendously low-res (especially for a 2017 paper), but it nevertheless shows some interesting things. For the sake of clarity, I colored asexuality in light blue.

Based on what I’ve measured from the diagram, autistic males show about 8.25% asexuality (compared to 0.8% in neurotypical males), while autistic females show about 22% asexuality (compared to 1.5% in neurotypical females).

And as you can see, the autistic groups also reported higher rates of homosexuality, bisexuality, and pansexuality; and lower rates of heterosexuality. Autistic women also show the greatest variety in sexual orientations in general.

Asexual sentiments

The most common sentiment from the asexual participants of the 2021 study on autistic people was that they had no sexual attraction to others. One 22-year-old man noted:[36]Beyond the Label: Asexual Identity Among Individuals on the High-Functioning Autism Spectrum (Ronis et al., 2021)

I don’t care or desire any type of relationship with

another person. I have no sexual desire or attraction.

Another person said:

I have no sexual feelings for anyone at all. I do not get ‘crushes’

on people and do not feel aroused looking at any people.

A third person stated:

I am not interested in sexual relations with

other people. I find it too overwhelming.

But sexual identity can be complex and confusing; not every autistic person who lacks sexual attraction clearly identifies as asexual. As one 34-year-old woman stated:

I wasn’t entirely comfortable checking the asexual box and considered checking unlabeled or unsure… But I suspect my sexual identity would be described by others as asexual if known.

In talking with my autistic friends, I’ve also noted a lack of clarity on whether they actually experience sexual attraction, what sexual attraction even entails (especially when there is sex drive and potentially a desire to have sex, but no sexual attraction to other people), or whether it makes sense to identify as asexual when in rare circumstances there is a desire to engage in sex. I’m very curious if the ambiguity and lack of clarity on whether we experience sexual attraction could be associated with alexithymia.

What puzzles me, though, is that while the prevalence of asexuality among autistic people could be as high as 19.2%, all autistic women in my personal life seem to fall on the ace spectrum. What kind of bias is there that the prevalence of asexuality is close to 100% around me? Am I an asexuality-magnet? 😆

Causes of asexuality

So what causes asexuality in autistic people? I have been able to find several different reasons:[37]Beyond the Label: Asexual Identity Among Individuals on the High-Functioning Autism Spectrum (Ronis et al., 2021)

- Most of the literature seems to point at asexuality being a sexual orientation, which suggests that—like other sexual orientations—it’s a pretty stable construct[38]Beyond sex: A review of recent literature on asexuality (Hille, 2023)

- Some autistic people experience sensory dysregulations[39]Qualitative Exploration of Sexual Experiences Among Adults on the Autism Spectrum: Implications for Sex Education (Barnett & Maticka-Tyndale, 2015)[40]Sexual Orientation in Autism Spectrum Disorder (George & Stokes, 2017) which can cause sensory-related asexuality. One study found that many of their participants reported that some of the sensations they experienced during sexual activity were unpleasant due to hypersensitivity[41]Qualitative Exploration of Sexual Experiences Among Adults on the Autism Spectrum: Implications for Sex Education (Barnett & Maticka-Tyndale, 2015)

- Some autistic people reported sensory-related issues with sex due to a lack of awareness of physical sensations—including arousal during sexual activity. This suggests a lack of sexual pleasure due to hyposensitivity[42]Qualitative Exploration of Sexual Experiences Among Adults on the Autism Spectrum: Implications for Sex Education (Barnett & Maticka-Tyndale, 2015) It’s also possible that alexithymia plays a role in the lack of awareness of physical sensations, although I haven’t been able to corroborate this hypothesis with research

- There is also some evidence that the increased likelihood and occurrence of prior sexual trauma could lead autistic people to identify as asexual[43]The Co-Occurrence of Asexuality and Self-Reported Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Diagnosis and Sexual Trauma Within the Past 12 Months Among U.S. College Students (Parent & Fertiter, 2018)

- And finally, it’s also possible that traits associated with autism—such as challenges in social interaction and communication, the aforementioned sensory issues, and possibly alexithymia—may weaken the strong links typically found between sexual

attraction, romantic attraction, and sexual behavior in neurotypical populations, thus leading to diminished sexual behaviors, with some autistic people self-identifying as asexual or somewhere on the ace spectrum as a result[44]Beyond the Label: Asexual Identity Among Individuals on the High-Functioning Autism Spectrum (Ronis et al., 2021)

Negative experiences impacting sexuality

I would like to add my own experience here as well. I’m not sure this constitutes trauma necessarily, and I don’t know to what extent it contributes to me being on the ace spectrum (my autism and suppressing my testosterone could be more significant contributors), but this has definitely impacted my sexuality and how I look at myself.

I think my parents made a lot of statements as I grew up that negatively impacted my sexual development. My dad used to make a lot of homophobic jokes, which made me feel uncomfortable, and it contributed to me feeling unsafe to come out as trans. Largely due to my dad’s comments, I didn’t come out to my parents until I was 19; and I didn’t dare to wear nail polish when visiting my dad, as I feared being judged by him. And once I hit puberty, my dad thought it was hilarious to start calling me and my brother masturbators. He did this often. It made me feel gross and ashamed of being sexual.

My mom inadvertently exacerbated these feelings. As a teenager, she was raped by her boyfriend and two of his friends. I think largely because of that horrendous experience, my mom would often comment on how gross men were; and how they were so sex-obsessed. She would make these comments about men being gross every time my dad made any sexual comments or jokes, which was fairly frequent. So I grew up feeling ashamed of being male and having sexual desires. It really troubled me during my romantic relationships, and even today, it makes me uncomfortable and unlikely to initiate sex.

My parents also objectified the opposite sex a lot. My mom would comment on men on TV she found hot. My dad didn’t do this as much, but I remember one time when I was in my mid to late teens, I was watching TV with my dad when a Dutch female rockstar came on who my dad was a fan of, and he said something like, “Oh God, look at her; wouldn’t you want to fuck her?” No dad, I wouldn’t. I don’t know if that response was innate or if it’s what I internalized from my mom’s judgments of men. Either way, I found it incredibly crass, and highly inappropriate—also because my parents were still married at that point.

There are more bad experiences, but I think you get the point. I think the antiandrogen I’m taking contribute significantly to my abrosexuality, and the fact that my sex drive is so diminished honestly feels like a relief to me. But why that feels like a relief probably has a lot to do with my childhood experiences. My sexuality has brought me a lot of confusion and distress, so I’m kind of glad I don’t have to deal with it as much now. But even before my transition, I think my sexuality was very constrained by my childhood experiences.

Even without the trauma, though, I think I would always have been demisexual. For me, sex is about love, intimacy, and experiencing mutual pleasure. I can’t engage in sex with any of those factors missing, and I could only have sex with someone I feel very close to, and someone I trust. I don’t take sex lightly.

Asexuality & distress

Asexuality is usually not accompanied by significant distress over one’s lack of sexual attraction or desire,[45]Asexuality: An Extreme Variant of Sexual Desire Disorder? (Brotto, Yule & Gorzalka, 2015) but of course distress may be experienced in some circumstances:

- When there is sexual desire but no sexual attraction, which can be an obstacle in pursuing sex

- When sensory challenges undermine one’s ability to enjoy sex, even if there is a desire to be intimate with one’s partner

- When other people impose sexual expectations on you, like a partner requesting sex while you take little or no enjoyment in it

- When you judge yourself over societal expectations—in particular, when men connect their masculinity with sexual performance, despite not desiring sex

- When you desire sex or intimacy in principle, but due to sexual trauma and PTSD, you are unable to act on your physical urges and/or sexual desire

Asexuality & satisfaction

Not only is asexuality generally not accompanied by distress, but it can actually have some positive associations as well! One study based on young autistic women (18–30 years old) indicated that while asexual autistic women show less sexual desire and fewer sexual behaviors than those with other sexual orientations, they actually reported:[46]Brief Report: Asexuality and Young Women on the Autism Spectrum (Bush, Williams & Mendes, 2021)

- Greater sexual satisfaction

- Lower generalized anxiety symptoms

Fascinating, isn’t it? Lesser sexual desire seems to lead to happier, less encumbered lives on average. Although the greater sexual satisfaction puzzles me, I think it makes sense that diminished sexual desire is associated with lower anxiety—at least in relationships where there aren’t any significant expectations of sex.

After all, if you do desire sex, the inability to find a sexual partner can lead to stress, a lack of satisfaction from sex can lead to stress, and insecurities around sexual performance can lead to stress. But also, a lack of a sex life could allow you to spend more time on other activities that may be more satisfying, productive, and enduring.

So rather than feeling sorry for people on the asexual spectrum, you are actually completely justified in envying us. 😉

Take an asexuality test

Are you unsure whether you’re asexual? The AIS-12 below is a self-report questionnaire to assess asexuality, and it’s designed in such a way that it will give a valid measure of asexuality irrespective of whether you self-identify as such.

Comments

Let us know what you think!