Natalie wrote a deeply resonant and evocative article on How autistics grieve. Reading her article, I realized I’m eager to talk about my own grief—in part as a way to process the ongoing pain I experience about our sweet Pluto’s passing last January, as I find it difficult to externalize my feelings about it, yet they come up often. I don’t know what to do beyond a brief cry and moving on—focusing on other things to distract from my grief and my inability to do something constructive with my feelings. And I figured it might be of help to myself and others to explore the research literature on the differences between how autistics and neurotypicals grieve and experience loss.

Pluto’s passing & grieving rituals

We both cried a lot when Pluto got into crisis and had to be held at the animal hospital. His prospects were very uncertain. Actually, his prospects were not good at all, and we were told it would be medically justified to put him to sleep, but the doctor understood if we wanted to continue monitoring him and doing some tests to see if there was something that could be done. Of course we were going to do everything in our power to help him, no matter the cost! And although he was 23 years old already, which I know is way older than most people could hope for, his downturn was so sudden and unexpected, we weren’t ready to let him go, and we loved him too much to give up on him. That night, I cried myself to sleep.

The next morning, he showed no improvements, and we were confronted with the fact that—in all likelihood—he wasn’t going to come back from this, and that it would be cruel to put him through more testing in a desperate attempt to try the impossible. With pain in our hearts, we decided to put him to sleep. We were both beyond consolation. Before Pluto was given the drug that would put him to sleep and stop his heart, Natalie held him for a while, and I stroked his sweet little head. Natalie’s son played Pluto’s favorite song on the guitar (a song that always drove Pluto to come closer to Natalie’s son as he practiced it). I tried not to cry so as to be strong for Pluto. I don’t know how conscious he was of his surroundings, but he deserved to pass surrounded by smiles rather than sorrow, having to feel concern for us.

I never understood funerals and any of the grieving rituals (which the research literature refers to as Peri-Bereavement Events, meaning events before and after a death), like visiting someone’s grave.[1]Understanding the Neurodiversity of Grief: A Systematic Literature Review of Experiences of Grief and Loss in the Context of Neurodevelopmental Disorders (Mair et al., 2024) But I understood the need for rituals in that moment. I now realized, it’s a significant way to say goodbye to your loved one and process the fact that they are truly gone—or that they’re about to pass.

Grieving vs. suppression

In the first few days, we both cried frequently. In fact, in the first two days, we cried for a large part of the day. It was exhausting, but necessary. In the days thereafter, I started crying less frequently, and usually my crying would be triggered by Natalie’s crying. I concluded that there were two things happening here:

- Natalie crying allowed me to access my own grief around Pluto, so I cried with her to let it all out.

- I felt pained by Natalie’s sadness, so part of the reason I cried was that I found it hard to see her suffer.

The more time passed, the less I cried. I guess part of this is only natural and healthy. The grieving process doesn’t continue perpetually with the same intensity. I will always grieve Pluto, but in smaller moments now, as opposed to crying all day and not being able to do anything else. But part of crying less I think was less conducive. I noticed that it felt like a relief every time I was able to distract myself. I focused more on my hobby of researching chess sets, and tinkering on my own chess sets, like restoring chips or weighting them. Sometimes I could get lost in one of these endeavors for hours, and then wake up from a seeming slumber, realizing I hadn’t thought of Pluto for hours. This isn’t necessarily bad I think; we have to find ways to move on and to find purpose beyond the grieving. But it felt like every time my mind went elsewhere for hours, I was no longer mindful; I was no longer processing my grief, but instead pushing it aside. I noticed my alexithymia—which I think has significantly decreased in the last years—came back in full swing. I think it’s because my sadness had been so deep and enduring for so long that it became overwhelming, and alexithymia kicked in as a protection mechanism. But as a result, I could no longer readily access my feelings.

I experienced a strange contradiction of feeling relieved when I no longer had to think of Pluto and grieve, but then also feeling relief every time I was able to—to cry again and process the feelings that became repressed and stuck.

Seeming indifference & a lack of grief

Neurodivergent experiences of bereavement and grief can often go unaddressed or misunderstood; in children, it can even be misattributed to “challenging behaviors.”[2]What we have learnt about trauma, loss and grief for children in response to COVID-19 (Fitzgerald, Nunn, & Isaacs, 2021) And this isn’t just a matter of miscommunication or misunderstandings between autistics and neurotypicals; it can occur between autistic people as well. For instance, Natalie misunderstood my grief around Pluto.

As a result of the alexithymia and repression, I guess I became seemingly indifferent to Pluto’s passing. I really wasn’t; internally, I was still sad and trying to cope with all the complex feelings. But externally, I stopped showing much of it. It made Natalie angry, as it seemed to her that I had gotten over him, and that his life and death ultimately didn’t matter all that much to me. She couldn’t be further from the truth. I explained to her that I was dealing with all these complex feelings, but that I could no longer readily access them and express them like before. At least once a day, I would briefly cry, but I no longer experienced meltdowns out of despair. Natalie was still experiencing those.

I also realized that the way I kept my feelings inside instead of expressing them related to my childhood. I grew up with my dad judging my mom every time she had a meltdown or panicked out of concern for her children, saying things like. “Act normally!” and “You’re being irrational!” It taught me that big emotional displays were irrational and wrong, and that you had to suppress them in order to be rational and stable. I was effectively taught to be more alexithymic. Plus, most of the times that I was sad or angry—especially when it was due to something my parents did—my feelings were never validated. If I had complaints about how they behaved towards me, I was told things like, “Our house, our rules. If you don’t like it, go live somewhere else.” It taught me there was no space for my feelings. Every time my emotions ran high, I would go to my room to “cool down”; to take time to transition back from that allegedly irrational emotional state to a calm and rational state. I grew up believing logic is the antithesis of emotions. It would take me decades to understand that logic bereft of emotions is cold and often cruel, and that you function best when you use both in unison and in moderation; you don’t become more rational and stable by suppressing and repressing your emotions.

But though I learned that important lesson years ago, I found myself subconsciously pushing my feelings deep down. And that absolutely didn’t serve me.

The grieving process & scheduling in grief

It’s interesting, because last week it felt like Natalie and my experiences of grief had switched. She mentioned that she felt she was over Pluto now, and I started silently crying. I still cry every few days when I think about him. And I cried a lot while writing this article—especially the part where I described Pluto’s passing. Writing this article has been cathartic, which surprised me a little. I mean, I knew immediately after reading Natalie’s article that I needed to write one of my own, as I felt like I needed to have a voice—to have a channel of expression. But I didn’t quite realize how healing it would feel to write about my feelings. It makes sense though. My therapist recommended a while ago that I should schedule in time to grieve, which admittedly sounds strange. My first reaction was, “How can I possibly grieve on command?” But it’s not like that. What she suggested was that I should take time at least once per week to take a walk in the areas where Pluto loved to go, for instance—like the big park, the smaller park full of flowers, or the area close to Ontario Lake. If I do that and I don’t cry, that’s fine; I don’t have to. But it would give me a context in which I may be able to access my feelings, and it allows me to actually make time to grieve, rather than to continue looking for escapes and distractions; to have at least half an hour per week where I can process my feelings and allow them to get unstuck. And I actually haven’t done that. Maybe because it has been too cold, but probably also because it has been too painful. I actually feel really motivated to visit those places right now. I think it will be good for me.

Natalie and my roles and positions in our grieving process haven’t really switched though. Natalie just thought for a moment that she was over Pluto, but on that day she looked at his paw print, so clearly she is still thinking about him. I think she cried again yesterday, as well as today. We’re probably both going through various stages of grief.

Stages of grief

In fact, let me go through Dr. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’ five stages of grief.[3]The five stages of grief (Kübler-Ross & Kessler, 2009)[4]On death and dying (Kübler-Ross, 1969) Perhaps to offer you information about the process if you weren’t yet familiar with it, but certainly for my own benefit, to check which stages I have gone through so far:[5]The Grieving Process | Martens Warman Funeral Home

- Denial – “At the beginning, you may feel a sense of detachment, shock, or numbness. You may even wonder why you are not more upset over your loss. This feeling of disconnection is a survival response.”

- Check. I didn’t wonder why I was not more upset over my loss, but clearly Natalie did, and it unsettled her.

- Anger – “Anger provides a bridge of connection from the initial numbness of grief. You may find yourself angry at the doctors, your family, the loved one who died, or at God. Anger is a necessary stage of the healing process.”

- I don’t know about this one. I feel the doctors did everything they could have done. The lead doctor even implied that it would be a good time to put Pluto to sleep, but offered us the option to do more, which we did. There is no one to be angry at. Except maybe myself. I felt sorry for the times I pulled on Pluto’s leash to urge him to walk, instead of comforting him and being patient with him until he started walking again. I did show a lot more patience eventually, but it was a difficult period when Pluto went from happily walking everywhere, to refusing to walk. At first, I thought it was laziness. Later I understood it was probably because of his losing eyesight, and perhaps also bodily pains. I’m upset with myself for not always understanding his experience and needs, and for not being more accommodating. At the same time, I know I was loving and nurturing most of the time. And everyone gets frustrated sometimes with their pet. But I know I gave him a good life to the best of my abilities.

- Bargaining – “Before and after a loss, you may feel like you would have done anything if only your loved one would be spared. “If only” and “what if” becomes a recurrent thought. Guilt often accompanies bargaining.”

- Check. Despite having done more testing and accruing thousands of dollars of medical fees for just that night, I asked myself, what if we had done more? What if we took the time to find out if he was dealing with a stomach ulcer instead of cancer, and we fixed the issue? What if we had done an autopsy to find out what actually went wrong? I feel knowing what happened to him would bring me comfort. But imagine finding out in the autopsy that what happened to him was a relatively easy fix, if only we had known the issue? I would never forgive myself. But no, we made a very rational and kind choice. Even if he had been able to recover, there was no guarantee he would have a similar quality of life, and we didn’t think it was reasonable to put him through more tests and cause him discomfort just because we weren’t ready to lose him. We made the choice that was the kindest to him. And his passing went fast. We could have inevitably prolonged his suffering. Had we done that, I would have wondered, “What if” all the same, and be angry at myself for not letting him go when it was clear that it was his time.

- Depression – “After bargaining, feelings of emptiness and grief present themselves on a deeper level. This depression is not a sign of mental illness. It is the appropriate response to a great loss.”

- Check. Although I’m realizing that I have not allowed myself to experience it fully. I realize I have been overspending on acquiring beautiful chess sets for myself and for Natalie. It gives me dopamine and joy every time I manage to get Natalie something truly special, and it will give me joy again when I find an opportune time to gift her those chess sets. But now I’m also experiencing the financial pressure from having overspent. I feel guilty about having accrued brokerage fees Natalie and I had no idea were a thing, so now Natalie has been calling different organizations to try to settle the bills. I feel uncomfortable now that beautiful gestures have turned into financial and emotional burdens. And I’m realizing now that none of my actions have resolved my grief, obviously. It was just escapism, but I can’t escape the inevitable. I feel empty and alone now.

- Acceptance – “Eventually, you come to terms with your bereavement as you move into the acceptance stage of grief. At this point, the loss has become part of your story and your history. It does not consume your life in the same way it did to begin with. With acceptance comes increased peace.”

- I don’t know about this one. I think I experienced glimpses of acceptance, but I certainly haven’t fully come to terms with it. I think I have a lot more to process, as evidenced by this article, and the fact that I’m crying now. The process isn’t complete once I’ve finished this article, either. It’s an ongoing process.

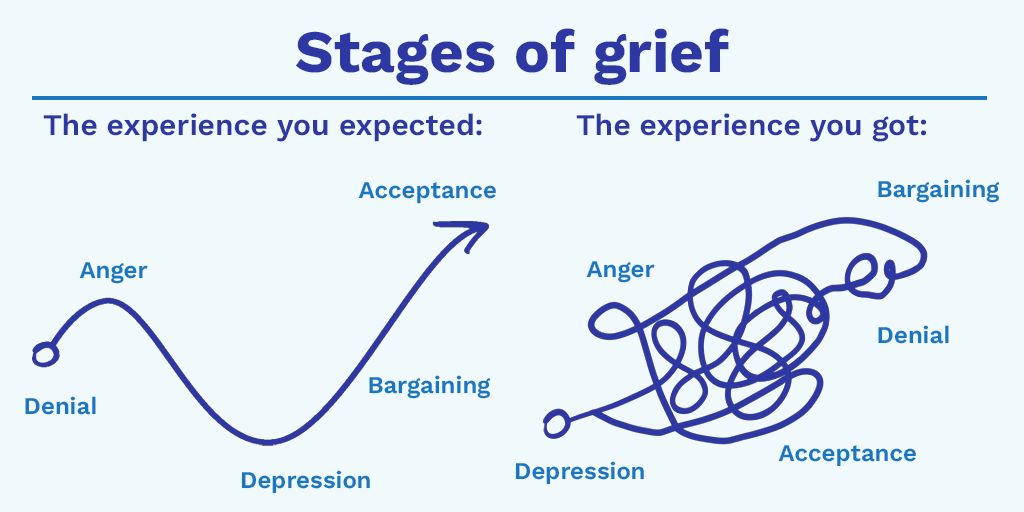

I should add though that the five stages of grief outlined above don’t necessarily occur in that order and some of them may not occur. Kübler-Ross and Kessler later noted that not everyone goes through all of them or in a prescribed order.[6]On grief and grieving: Finding the meaning of grief through the five stages of loss (Kübler-Ross & Kessler, 2004) And some stages may resurface; one study concluded that instead of a stage-like progression, emotional well-being appeared to oscillate back and forth following a loss.[7]Emotional well-being in recently bereaved widows: a dynamical systems approach (Bisconti, Bergeman, & Boker, 2004)

But I think most importantly—perhaps especially for neurodivergent people—we shouldn’t get the impression that the five stages above are the only way to grieve.[8]Stages of Grief Portrayed on the Internet: A Systematic Analysis and Critical Appraisal (Avis, Stroebe, & Schut, 2021)

The impacts of loss & change

One characteristic of autism is our resistance to change and difficulties with change and transitions (see criterion B of the diagnostic criteria for autism),[9]Unexpected changes of itinerary – adaptive functioning difficulties in daily transitions for adults with autism spectrum disorder (Rydzewska, 2016) but how this impacts our experience of grief and loss is less studied. But it’s suggested that these difficulties navigating change and transitions—alongside difficulties and differences in understanding, expressing, and regulating emotions—make us particularly vulnerable to grief, bereavement, trauma, and non-death loss.[10]Understanding the Neurodiversity of Grief: A Systematic Literature Review of Experiences of Grief and Loss in the Context of Neurodevelopmental Disorders (Mair et al., 2024)

Challenges associated with unexpected changes in routine, sensory difficulties and social interactions are difficult enough to deal with already; they impact our adaptive functioning skills (skills we use to navigate and succeed in daily life) by adding complications in the process of navigating transitions between different contexts and situations.[11]Unexpected changes of itinerary – adaptive functioning difficulties in daily transitions for adults with autism spectrum disorder (Rydzewska, 2016) But the experience of loss is a hugely compounding factor—whether it’s the loss of a loved one through death, the loss of a friendship, or going through a breakup or divorce. Any of these experiences undermine our established routines, our dopamine sources, our support network, and so forth. And it can undermine our sense of purpose and our energy (our Spoons), resulting in depression and autistic burnout.

When one of my best friends suddenly dramatically reduced contact over Christmas in 2023, at first I was just confused. Then I became concerned. They assured me nothing had changed and that they still felt the same about me, but our relationship went from daily contact to them ignoring me for several weeks at a time. One thing that made it incredibly difficult for me to adapt to this change is not understanding the ‘why’. Is it something I did? Am I not fun or worthwhile? It really impacted my self-esteem, and the fact that I didn’t get a clear explanation and was essentially gaslit made it impossible to process what was going on. Over time though, I began to understand that there really was no retrieving or reviving our friendship. Although the explanation eluded me for about a year, I started to come to terms with the fact that I experienced a great loss. I lost my best friend, and for many months I had to grieve the loss of our friendship, the loss of a significant part of my support network, and the loss of someone who boosted my self-esteem through our mutual enjoyment of each other. I also found it was quite a bit more complicated to grieve the loss of a relationship when that person is still around—alive and well. Pluto’s passing was immensely difficult to deal with, and I haven’t experienced such profound sadness and grief in well over a decade. But at the same time, I realized that the grieving process itself was a lot less complicated. For one, Pluto loved me to the very end, so that feeling endured after his death. His passing didn’t make me wonder about whether I’m worthwhile. As painful as it was, the grief was simple; my feelings were uncomplicated. And although I still cry about Pluto, I’m finding I’ve made a lot more progress in processing the grief in the last three months than I did with my friend in almost a year. It’s easier to adapt to this new situation because it’s a simple one; Pluto is just gone, and that’s it. It allowed me to start the grieving process immediately instead of having it delayed by confusion about what the situation actually is.

It is difficult when someone leaves—it means there’s a gap to fill, and it may take some time to fill the gap. And it’s hard—it’s hard.[12]Saying goodbye: How people with learning disabilities and staff experience the end of key working relationships (Mattison, 1998)[13]Understanding the Neurodiversity of Grief: A Systematic Literature Review of Experiences of Grief and Loss in the Context of Neurodevelopmental Disorders (Mair et al., 2024)

What eventually helped me to start getting over the grief about the loss of my best friend, and what helped me to get on with my life, was to find a new special interest. I got into researching and collecting Soviet chess sets, and through this hobby, I found a small community of fellow chess collectors. Through our common interest, I felt a sense of kinship and community that filled the void my best friend left—at least a little bit. And as I soon found out, I’m confident that most of those chess set-obsessed people I interact with are autistic as well. I don’t think that would surprise any autistic person.

In order to get over my loss (well, mostly; I’m still dealing with it today), I had to find a new purpose, a dopamine source, and a social network. I had to radically revise some of my daily routines, which was a process that took several months. And I think this is one of the most significant differences in the experience of grief between autistic people and neurotypicals; how loss undermines our routines, which urges us to evaluate and revise almost everything about our daily functioning. In the research literature, this is described as ‘Loss on Loss’, meaning secondary losses following an initial loss, such as a change in living circumstances following a bereavement; and this was experienced by most neurodivergent people; yet the significance of secondary loss(es) are often unrecognized.[14]Understanding the Neurodiversity of Grief: A Systematic Literature Review of Experiences of Grief and Loss in the Context of Neurodevelopmental Disorders (Mair et al., 2024)

Another challenge is adapting to change. Since individuals on the spectrum like routine and doing things the same way, this can be a challenge with the third task of mourning: external adjustments. New routines have to be established, especially if the deceased person was part of the individual’s daily life.[15]Bereavement and Autism: A Universal Experience with Unique Challenges (The Arc of the United States) (Graham, 2013)

– Elizabeth Graham

Obviously loss has a big impact on neurotypicals all the same, but I imagine they are much more adept at adapting to new situations; and they probably have less rigorous routines, which are thus less impacted by a significant change. You might say they lack loss on loss. 🤭

Lack of a grief response

When it comes to deviating experiences of grief, it’s not just how our grief or seeming lack thereof appears to others that can have a negative impact; how we grieve differently—seemingly or actually—can harm ourselves, too. That was certainly my experience when my grandmother died.

When my grandmother died a few years ago, I didn’t really feel anything about that—except for the guilt of not having contacted her in the days leading up to her passing (I live in another country, so calling was my only way to contact her). I was just too anxious to give her a call. What would I even say? Phone calls on birthdays were already frightening to me. They were always awkward, and due to not knowing what I could meaningfully say, they invariably consisted of the same formula of congratulating, asking what they had done to celebrate it, followed by a pause and one of us saying something like “Okay then” to bring the conversation to an end. My anxiety would always spike before calling, and often I would cry after the phone call out of relief of it being over. But what could I possibly say when your family member is dying? Asking how they’re doing doesn’t strike me as appropriate. If I had a deep connection with the person, it would be trivial to find something meaningful to say, and just express my love for them, and the sadness I experience of them leaving soon. But I didn’t have such a deep relationship with my grandmother. I guess this sounds wrong, but I was relieved to learn from my father that my grandmother had been mostly unconscious in the days leading up to her passing, so there would have been no point in calling anyway.

As for what I felt about her passing… I felt sad for my father, who had just lost his mother. But I had no personal experience of loss or sadness. And that troubled me. I experienced nothing when my uncle died years earlier, but we were never close, so that made sense to me. I never had a deep relationship with my grandmother either, but I often slept over as a child, and for most of my life, I visited her on Sundays. Surely I ought to feel something about someone in my immediate family passing? But nothing… I talked with my father about this, how I felt so wrong for my absence of feelings. He assured me that it was all okay—that we all grieve in different ways, and whatever we feel or don’t feel is all okay. We have no control over that. Maybe others will judge you if you don’t cry when they consider that to be an appropriate response. But we aren’t wrong for whatever we feel or don’t feel. That was very meaningful for me to hear.

As for my father’s grieving process—who definitely has autistic traits—his grieving process was fairly quick. He felt his mother had a pretty long and good life, and he was just relieved that she no longer had to suffer. I don’t know what my father’s internal experience is like, but at least from the outside, he seemed to have taken the death of his mother pretty well—at least much better than his four non-autistic sisters.

Hidden grief

But this brings me to another theme that showed up in various papers, which is hidden grief. What happens when our alexithymia complicates expressing our grief even if it’s deeply felt internally? What happens when our flat affect/reduced affect display doesn’t show others how deeply we experience a loss? Autistic people can suffer a lot when their grief reactions go unrecognised, unseen, and unheard.[16]Understanding the Neurodiversity of Grief: A Systematic Literature Review of Experiences of Grief and Loss in the Context of Neurodevelopmental Disorders (Mair et al., 2024)

He [my therapist] leaned forward and encouraged me to describe how crying felt. I thought about it for a moment and told him very sincerely that it made my eyes hurt … It was only much later that I realized he meant the other felt. I still don’t know how to answer that one… How does crying feel?[17]Autistic Grief Is Not Like Neurotypical Grief (Fisher, 2012) | Thinking Person’s Guide to Autism

– Karla Fisher

But hidden grief wasn’t always unintended and unwanted; some neurodivergent people will attempt to hide their own grief (camouflaging) so as not to further burden those around them. Maybe that’s what my dad did in order to give me space to explore my own feelings, without feeling I need to take care of his? I have no idea.

I don’t want my dad to be sad, so I don’t

talk to him that I miss my mom.[18]A Photovoice Study: The life experiences of middle-aged adults with intellectual disabilities in Korea (Kim et al., 2021)

– Daehyun

Others—particularly autistic people—showed less understanding of the broader impacts of their grief at the time, and masked to fit in with the expressions of grief in their surroundings while hiding their lack of understanding as to what the grief may mean to others.

I have no blueprint for … what to expect in the social situations that have come with an event like this. I have been forced to guess my way through, at a time when my typical abilities are compromised by the emotional overload brought about by loss and grief.

– Soraya

This was definitely my experience when I was younger, although I made no attempts to fake expressions of grief.

Logic & understanding loss

Lastly, I want to cover something I described with respect to the loss of my friendship more broadly, which is the need to understand the loss and the reasons for it. I think this is highly characteristic of autism, and in fact Natalie has described before how it became apparent in her clinical practice that autistic people are often better at overcoming grief and trauma than neurotypical people when they understand the ‘why’; as soon as the reasons are understood, they can start processing their pain, and get over it relatively quickly. But on the flip side, we can get hopelessly stuck in our grief and trauma when explanations elude us.

The need to know can be a powerful tool to process grief, and it often takes the form of trying to acquire as much information about the loss as possible—spending a lot of time reading and learning about a specific loss, as well as more general conceptualizations of grief. This can even elevate to the level of a new special interest:

My mom’s death and my later diagnosis have influenced me to take a special interest in the uniqueness of bereavement in individuals with autism spectrum disorder.

When my mom died, obituaries became my interest. I would go online and sign obituary guest books of people who died in a similar way as my mom. I have no siblings so doing this helped me cope and feel less alone.[19]Bereavement and Autism: A Universal Experience with Unique Challenges (The Arc of the United States) (Graham, 2013)

– Elizabeth Graham

My deepest experiences of grief

As a final note, I just realized that my three deepest experiences of grief in my life encompass three different types of losses:

- Romantic relationship – When my girlfriend of 3.5 years broke up with me when I was 19, I was absolutely devastated. What complicated the grieving process for me was that I was never offered a satisfactory explanation for why our relationship ended. “A change of heart” was all I was offered as an explanation. I didn’t get it. It was quite a while later that I discovered what “a change of heart” meant was that she had met someone else, and that she had been cheating on me for a few months before she broke up with me. I cried every night for about a year, and it took me 3 years before I started to get over the loss. I remained single for almost a decade after this relationship, and the final bit of grief I only managed to process during my relationship with Natalie.

- A significant friendship – I’ve had many friendships fade and at least one ended fairly abruptly, but none of them caused me grief, except for the one relationship discussed in this article. It hit me so hard because we had such deep trust which I’ve only had with Natalie and my other best friend; we had so much fun, fascinating and meaningful discussions, and I loved her dearly. I don’t make friends easily, and she was the first new and deeply meaningful friendship I made in many years. The loss of this relationship resulted in great insecurity about people in general. How can I trust people when someone you thought loves you exactly as you are just gets bored of you and moves on, like you meant nothing? I experienced the same with my ex, and it caused the same distrust in people, which is why I kept most people at a distance for so long. I still do, actually. I’m quite open, yet it’s not easy to get truly close to me.

- The loss of a loved one – I think it’s interesting that I never grieved a person. The only significant loss through death was my sweet Pluto. I don’t know how long it will take me to stop grieving, but what I’ve noticed is that the grief now, several months later, no longer cuts as deep as the grief of the previous two relationships. The reason being—as I discussed before—that this relationship and the reasons for the loss are fairly simple and straightforward, and I take solace in the fact that Pluto always loved me. Our relationship which I feel endures even now is uncomplicated and beautiful. It even strikes me as poetic that as I’m writing this, I’m ending this article with the shedding of tears, but with a calmness in my heart as well. I just really miss him. My dear Pluto.

Comments

Let us know what you think!