Black autistic torchbearers: Recognizing the unseen luminaries in history, advocacy, and the arts

Black autistic individuals have shaped history, culture, and advocacy, yet remain underrecognized due to systemic erasure, racial bias, and digital segregation. This piece explores their contributions, challenges exclusionary narratives, and calls for true representation and equity.

Introduction

Black autistic individuals have made significant but overlooked contributions to history, science, activism, and the arts. Their absence from historical records and contemporary advocacy is not incidental but the result of systemic erasure shaped by both racial and ableist biases. Black voices have been consistently excluded from autism research, leaving critical gaps in understanding, policy, and representation. This exclusion reinforces the false perception that autism is primarily a white experience, limiting access to culturally responsive support and advocacy.[1]The Scholarly Neglect of Black Autistic Adults in Autism Research (Malone et al., 2022)

A key factor in this invisibility is delayed and inaccurate diagnoses. Black children are diagnosed later than their white counterparts, leading to missed opportunities for intervention and necessary accommodations.[2]Race differences in the age at diagnosis among medicaid-eligible children with autism (Mandell et al., 2002) These delays are not accidental but stem from structural inequities in healthcare and education, where Black families frequently face misdiagnosis, dismissal, and inadequate resources. The lack of historical documentation, combined with contemporary disparities, creates a cycle of erasure that continues to restrict both recognition and advocacy for Black autistic individuals.

This article examines how systemic exclusion, digital segregation, and intersectional discrimination have shaped the experiences of Black autistic individuals while also celebrating their contributions. It highlights the resilience and achievements of Black autistic torchbearers, past and present, while exploring how algorithm-driven silos on social media separate Black autistic voices from mainstream autism advocacy.[3]Brief Report: Exploring Some Aspects of Social Activism in the Online Autistic Community (Bolton & Ault, 2019) As an autistic but non-Black writer, I approach this subject with a commitment to grounding this discussion in research and centring Black autistic voices. My goal is not to claim authority over these experiences but to synthesise existing knowledge, amplify marginalised perspectives, and recognise the brilliance of Black autistic individuals whose contributions deserve far greater visibility.

The historical invisibility of Black autistic individuals stems, in part, from the challenges of retrospective diagnosis. Autism as a formal diagnosis did not exist during the lifetimes of many historical figures, and even as understanding of neurodivergence has evolved, it remains shaped by racial biases. Black individuals have long been underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed due to systemic racism in medicine and psychology, a reality that persists today.[4]The Scholarly Neglect of Black Autistic Adults in Autism Research (Malone et al., 2022) Historically, Black children and adults displaying autistic traits were labelled as defiant, unintelligent, or emotionally disturbed rather than recognised as neurodivergent. Racist diagnostic biases and medical neglect have contributed to the ongoing failure to identify autism in Black communities, further marginalising those in need of support.[5]Examination of Race and Autism Intersectionality Among African American/Black Young Adults (Davis et al., 2022) Without access to diagnosis and accommodations, many Black autistic individuals have had to navigate a world that neither recognised nor understood their cognitive differences, reinforcing their exclusion from both historical and contemporary discourse.

The intersection of race and disability compounds this invisibility, subjecting Black autistic individuals to a double erasure. Structural racism ensures that Black individuals already face barriers to recognition, and ableism further marginalises those who are neurodivergent. In How Ableism Fuels Racism (2024), Lamar Hardwick (a Black autistic author, disability advocate, and PhD student) argues that ableism underpins racist structures, positioning Black neurodivergent individuals as either defective or dangerous within white supremacist frameworks. Black autistic traits are often misinterpreted as behavioural issues, rather than recognised as a distinct cognitive processing style. Research has shown that Black autistic children are more likely to be punished than accommodated, leading to over-policing in schools, exclusion from educational opportunities, and increased interactions with the criminal justice system.[6]Autism and the criminal justice system: Examining the experiences of autistic adults in England (Reid & Makin, 2021) These misinterpretations reinforce the false perception that autism is a white condition, pushing Black autistic individuals to the margins of both autism advocacy and broader social movements.

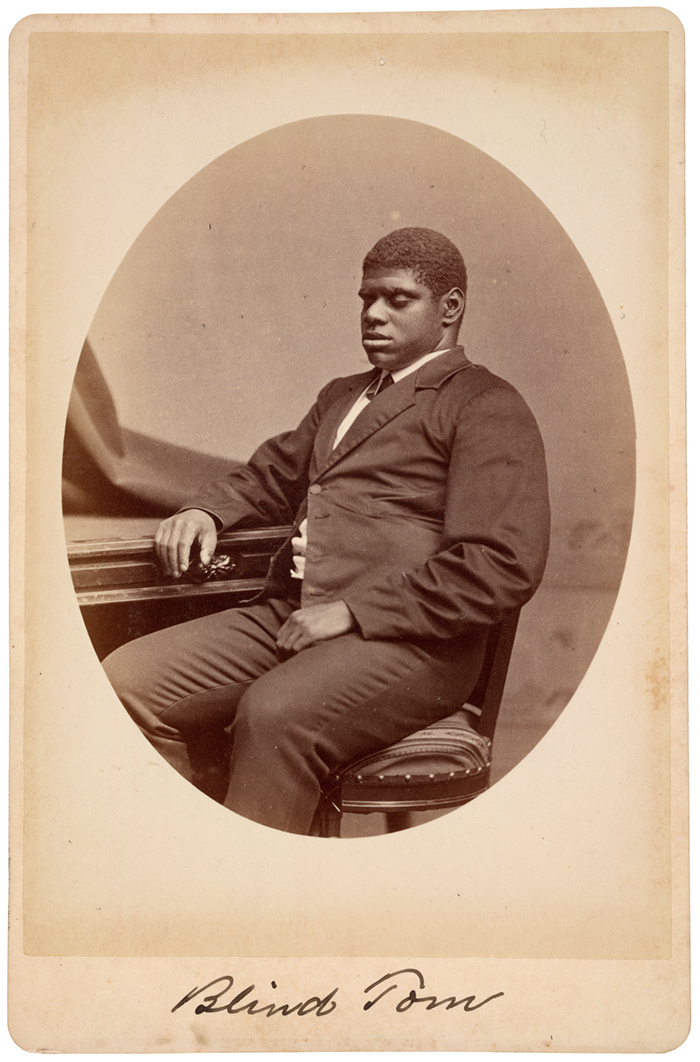

Despite these barriers, history offers glimpses of Black autistic individuals whose brilliance left an undeniable mark. One such figure is Thomas “Blind Tom” Wiggins (1849–1908), a musical savant born into slavery in the 19th century. Likely autistic, he possessed an extraordinary ability to play complex compositions from memory, astounding audiences worldwide. However, like many neurodivergent Black individuals, his talent was exploited, and he had no agency over his career or life, which was controlled by those who profited from him.[7]Re-examining the life of “Blind Tom” Wiggins: Autism, talent, and exploitation in the 19th century (Winter, 2021)

Another figure speculated to have been autistic is George Washington Carver (c. 1864–1943), the renowned agricultural scientist. His intense focus, adherence to routine, and deep engagement with scientific experimentation align with traits commonly associated with autism. While retrospective diagnosis is speculative, these examples challenge the notion that Black autistic individuals have not played a role in shaping history. Instead, their stories have been obscured by systemic erasure, and it is long past time for them to be acknowledged.[8]Re-examining the life of “Blind Tom” Wiggins: Autism, talent, and exploitation in the 19th century (Winter, 2021)

Addressing this historical and ongoing erasure requires active engagement from institutions with deep cultural significance. Hardwick (2024) highlights the Black church as a key institution that must be involved in discussions around disability and neurodiversity. Historically, the church has served as a centre for advocacy, education, and mutual aid in Black communities, yet autism and neurodivergence remain underdiscussed or framed through deficit-based perspectives. As a deeply influential institution, the Black church has the potential to reframe autism as an integral part of human diversity rather than something to “overcome.” Creating spaces for these conversations through sermons, community events, or faith-based support networks could help dispel stigma, increase awareness, and challenge the ableist structures that fuel both racism and exclusion. Ensuring that the Black church plays an active role is essential for fostering community-based acceptance and advocacy, rather than leaving Black autistic individuals and their families to navigate a system designed to marginalise them alone.

Intersectionality: The digital divide & structural exclusion

The intersection of race and disability extends into digital spaces, where algorithm-driven segregation reinforces the exclusion of Black autistic voices. Social media platforms now essential for advocacy and community-building are not neutral spaces. Engagement-based algorithms prioritise content with the widest appeal, creating silos that separate communities. This has led to distinct digital spaces like Black TikTok and Black Twitter, where Black users engage in conversations largely unseen by broader audiences. For Black autistic advocates, this means their work is often excluded from mainstream autism discourse, which remains dominated by white advocates. As a result, many white autistic activists are unaware of the knowledge-sharing and organising happening in Black autistic spaces, reinforcing long-standing racial disparities in autism advocacy.

This digital segregation is not incidental; it is an extension of real-world systemic exclusion. Studies on digital activism show that algorithm-driven bubbles limit marginalised voices, restricting their visibility and reach (Bolton & Ault, 2019). In response, Black autistic advocates have intentionally carved out their own spaces, using hashtags such as #AutisticWhileBlack and #BlackNeurodiversity to ensure their conversations reflect their lived experiences, rather than being filtered through a predominantly white neurodiversity movement. While these spaces foster community, self-advocacy, and knowledge-sharing, they also highlight a broader divide in autism advocacy, as social media algorithms keep Black autistic voices from reaching mainstream neurodivergent spaces. The result is a fragmented landscape, where white-led advocacy movements continue to set dominant narratives, often failing to account for the intersectional experiences of Black autistic individuals.

Despite these barriers, Black autistic activists continue to push for recognition and representation. Anita Cameron, a long-time disability rights activist and author, has fought to centre Black disabled voices in policy and advocacy, challenging their exclusion from disability justice movements. Similarly, Kayla Smith, another prominent disability rights advocate, founded Black Autistic Pride Day to combat the digital erasure of Black autistic individuals, creating a dedicated space for celebration and visibility. Their work underscores the resilience and determination of Black autistic advocates, who continue to push for inclusion despite systemic barriers in both digital and institutional spaces.

However, true inclusion cannot be left solely to Black autistic individuals. It requires intentional action from white autistic advocates to dismantle algorithmic segregation, amplify Black autistic voices, and ensure that their contributions are not just acknowledged, but actively integrated into broader autism advocacy efforts.

Creativity & innovation: How autism drives black excellence

Creativity and innovation have long been defining strengths of autistic individuals, with research highlighting how pattern recognition, hyperfocus, and heightened sensory perception contribute to unique artistic expression.[9]Are Children with Autistic Traits More or Less Creative? Links between Autistic Traits and Creative Attributes in Children (Smees et al., 2024) Autistic individuals engage deeply with their craft, producing intricate and highly original work that challenges conventional artistic norms. For Black autistic creatives, artistry is more than self-expression it is an act of advocacy, cultural affirmation, and resistance against societal erasure.

Black autistic artists have made profound contributions to the arts, using their work to explore themes of identity, neurodivergence, and Black cultural expression. Angela Weddle, a visual artist, is known for her immersive and textured pieces that reflect her autistic perception of the world. Her art captures the sensory depth of experience, offering a compelling representation of neurodivergence through colour, movement, and intricate detail.

Jennifer White-Johnson, a designer and activist, integrates disability advocacy into her visual work, using graphic design to challenge ableist narratives and celebrate neurodivergent identity. Her projects highlight the intersection of race, autism, and art as a site of empowerment, using creative mediums to amplify Black autistic voices. Similarly, Kaleb “Tangy Keys” Hanson brings neurodivergent-centred storytelling into the world of cartoons and digital illustration, creating characters and narratives that affirm autistic experiences while pushing for greater representation of neurodivergence in media.

Black autistic creativity is also deeply intertwined with parental advocacy and storytelling. Tiffany Hammond, a Black autistic mother, used her artistic talents to create A Day With No Words (2023), a New York Times bestselling picture book that follows a Black nonspeaking autistic child as he communicates with the world around him. The book challenges dominant portrayals of autism as exclusively white, offering a powerful representation of Black autistic joy, agency, and communication beyond spoken language. As both an artist and advocate, Hammond’s work demonstrates the power of creativity as a tool for autism acceptance and empowerment.

These artists, among many others, exemplify the richness of Black autistic creativity and the ways in which their work redefines artistic representation, advocacy, and communication. Through visual arts, design, storytelling, and literature, Black autistic creatives continue to shape the cultural landscape, ensuring that Black neurodivergent experiences are not only acknowledged but celebrated.

Yet, algorithmic biases hinder the visibility of Black autistic creatives, much like they do in broader digital spaces. Research shows that Black artists are less likely to be promoted in mainstream arts spaces, as engagement-driven algorithms prioritise white creators. As a result, Black autistic artists—despite their talent and contributions—often struggle for visibility, funding, and opportunities. This exclusion is not about merit but systemic inequities embedded in digital and institutional structures. Addressing these disparities requires more than recognition it demands active efforts to amplify Black autistic voices, ensuring that their work is valued, seen, and given space to thrive rather than relegated to the margins.

Activism & self-Advocacy: Fighting for representation in research & STEM

Black autistic individuals have long been underrepresented in research, with autism studies historically centring white participants and perspectives. This exclusion has created gaps in data, misinformed assumptions, and a lack of culturally responsive support.[10]The Scholarly Neglect of Black Autistic Adults in Autism Research (Malone et al., 2022) The failure to prioritise Black autistic voices has shaped policy and advocacy in ways that do not reflect their lived experiences, particularly how race and neurodivergence intersect. Without representation in scientific studies and public discourse, Black autistic individuals continue to face systemic barriers in healthcare, education, and social policy, reinforcing cycles of exclusion.

This underrepresentation is not incidental but a direct consequence of who has historically shaped autism advocacy. White mothers of autistic sons have dominated mainstream discourse, framing autism as a childhood condition rather than a lifelong neurocognitive identity. This parent-led model has prioritised early intervention and treatment over the needs of autistic adults, as seen in the Autism CARES Act one of the most significant autism-related laws in the U.S. The Act’s origins, inspired by an autism mom lobbying her congressman a fact once proudly displayed on the bill s original sponsor s website reflect the long-standing prioritisation of non-autistic parents’ concerns over autistic individuals’ autonomy. As a result, Black autistic adults, already facing structural neglect, are further marginalised in funding, research, and services, while resources remain overwhelmingly focused on childhood.

For Black autistic individuals, this exclusion extends beyond policy, feeding into racial bias, adultification, and criminalisation. The belief that autism is only a childhood condition renders Black autistic adults invisible in discussions about independent living, workplace accommodations, and self-determination. This invisibility is particularly dangerous Black autistic individuals are more likely to be misinterpreted as aggressive or noncompliant by law enforcement, denied disability accommodations, and excluded from vital services.[11]Autism and the criminal justice system: Examining the experiences of autistic adults in England (Reid & Makin, 2021)

Compounding this issue is the deeply embedded legacy of eugenics within the autism moms movement. Many parent-led organisations continue to advocate for cures and interventions that align with a eugenicist mindset, treating autism as something to be eliminated rather than supported. This is especially alarming given the long history of scientific racism and medical violence against Black communities. From forced sterilisation programmes targeting Black disabled individuals to unethical experiments such as the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, eugenics has long justified the dehumanisation of Black people under the guise of scientific progress. For Black autistic individuals, these narratives are not just exclusionary but actively dangerous, shaping medical policies that threaten bodily autonomy and reinforce systemic neglect.

Despite these barriers, Black autistic individuals continue to challenge their exclusion, fighting for representation on their own terms. Armani Williams, the first Black autistic NASCAR driver, has used his platform to push back against stereotypes about race and neurodivergence, advocating for a more inclusive understanding of autism. His success in an overwhelmingly white, non-disabled field is a reminder that Black autistic individuals exist in all spaces not just those dictated by white-led advocacy.

True representation requires rejecting the paternalistic narratives of autism moms and recognising the agency, expertise, and lived experiences of Black autistic individuals themselves. It also demands dismantling the deep ties between eugenics and autism discourse, ensuring that Black autistic people are not just included in research but actively shaping it in ways that affirm their dignity, autonomy, and humanity.

Community & cultural strength: Black-led support systems

Black families have long navigated autism without institutional support, instead relying on cultural traditions, community networks, and faith-based structures to meet the needs of autistic individuals. Systemic barriers including delayed diagnoses, medical racism, and the financial burden of private therapy have made accessing formal autism services particularly difficult.[12]Davis & Emerson, 2023 In response, many Black families have developed alternative support systems, prioritising collective care, intergenerational knowledge, and community-driven strategies over institutional intervention. These approaches reflect a legacy of resilience, ensuring that Black autistic children and adults receive care even when medical and educational systems fail them.

Despite these challenges, Black parents have been at the forefront of autism advocacy, fighting for their children’s recognition and access to resources in a system that continually overlooks their needs. Research shows that Black mothers, in particular, play a critical role as advocates, pushing back against misdiagnoses, securing accommodations, and challenging deficit-based narratives imposed on their children.[13]Davis & Emerson, 2023 Tiffany Hammond (2023) highlights this advocacy in her work, particularly in challenging the infantilisation of autistic children and advocating for Black autistic joy and agency in storytelling.

However, some of the most urgent concerns raised by Black parents are often dismissed outright by white neurodivergent activists. This is especially evident in the debate around Applied Behaviour Analysis (ABA), which is widely condemned by the white-led neurodiversity movement. While Black parents including Hammond criticise ABA’s origins in compliance-based training, they also acknowledge the stark reality that survival in an anti-Black world is not optional. Black autistic children are disproportionately perceived as threats, and many parents turn to ABA not as an ideal solution, but as one of the few available tools to help their children safely navigate a world that criminalises their existence. This nuanced discussion is often dismissed in white-dominated neurodivergent spaces, where the intersection of anti-Black racism, criminalisation, and police violence against Black disabled individuals is ignored. The conversation about ABA and alternative supports cannot be race-neutral Black families must weigh immediate physical safety against the long-term goal of dismantling ableist systems.

Lamar Hardwick (2024) argues that the Black church must take an active role in these discussions, as it has historically served as a pillar of support and advocacy within Black communities. Yet, conversations around autism and neurodiversity remain limited in many faith-based spaces, often framed through deficit models rather than as part of human diversity. By incorporating autism acceptance into church-led initiatives, Black faith institutions could provide critical advocacy, awareness, and support for families navigating autism in a system designed to exclude them.

Beyond faith institutions, Black-led autism organisations and community initiatives have emerged as vital sources of support, creating spaces where Black autistic individuals can connect and thrive on their own terms. These grassroots movements, driven by parents and autistic advocates alike, challenge institutional failures that have historically excluded Black autistic people, ensuring that support is built within the community rather than dependent on systems that have long marginalised them.

Conclusion: A call for recognition & celebration

Black autistic individuals have shaped history, culture, and activism, yet their contributions remain under-recognised. Their stories—whether those of historical figures whose neurodivergence went unnamed or contemporary advocates fighting for visibility—have too often been erased or sidelined. This piece is not an uncomplicated celebration, nor could it be. To truly honour Black autistic individuals, we must confront the systemic exclusion, racial bias, and structural violence they have endured. The realities discussed here the failure of research to represent Black autistic voices, the paternalism of white-led advocacy, the dangers of eugenicist narratives, and the algorithmic segregation that silences Black autistic creators are not just historical injustices but ongoing barriers that demand urgent redress.

White autistic advocates and researchers must actively seek out and amplify Black autistic voices, rather than assuming inclusion will happen organically. Future autism research must centre intersectionality, recognising that autism does not exist in isolation from race, class, or other aspects of identity. Acknowledging disparities is not enough; there must be a commitment to dismantling them. This means shifting away from white-centric narratives that dominate autism discourse and ensuring that Black autistic individuals are not only represented but leading the conversations that shape policy, research, and advocacy.

The brilliance of Black autistic individuals has always existed, whether or not society recognised it. It is long past time for their voices to be heard not as an afterthought or an exercise in tokenism, but as an essential, inseparable part of the autistic experience. Recognition must not be passive; it must be an active commitment to challenging exclusion, correcting injustice, and ensuring that Black autistic individuals have the space, resources, and autonomy to define their own narratives on their own terms.

Comments

Let us know what you think!