I—like many other autistic people—am puzzled by the realization that people, in general, don’t seem all that concerned with truth. Why is that, and why does it seem like truth is valued to a greater degree by autistic people?

Curiosity

I think there are many factors that could account for this or contribute to it. When I was younger, I assumed it depended on intelligence and curiosity. Without curiosity, you wouldn’t look for truth; and without intelligence, you wouldn’t recognize it. And I think these are indeed factors that contribute to our drive for truth. I also think that, given that for autistic people navigating the social world is often confusing enough, we come to rely on and appreciate facts a lot more, since learning more facts about the social world can make it easier to navigate that social world. But that doesn’t quite account for why I am looking up astronomical facts, and why I seem to be more invested in trying to understand reality than what I observe from people around me. It seems I enjoy discovering the truth and learning new things for its own sake.

But then, I was watching a lecture by cognitive scientist and philosopher Joscha Bach on computational meta-psychology (about how the mind—despite being a computational system—introduces biases that can subvert meaning and undermine rationality), and he presents a social framework that plausibly accounts for why people are generally not that concerned with truth. And it’s quite fascinating! Also, it’s probably true, so pay attention!

Social learning & synchronization

Bach explains how social learning leads groups to synchronize opinions, which is something I suspect most of us have noticed, even in ourselves. As much as I like to think I am a strong individual with my own opinions, I can see how even my musical taste has been informed by my experiences and interactions with others. Maybe it’s not necessarily my friends getting me into particular music styles, but my group identity and values that make me stay away from certain genres, which indirectly informs what I DO choose to listen to. Our opinions and preferences can synchronize with the groups we consider ourselves to be part of in subtle ways. As social beings, some level of conformity is probably inevitable.

Truth vs. opinion

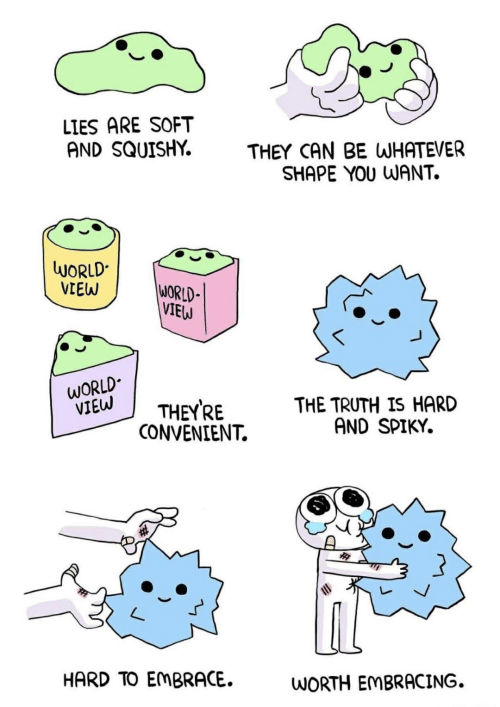

But here is something that surprised me quite a bit. The “best” opinion-forming system (in terms of what is most conducive to the individual members of any particular group and their relationship to the group) does not look for truth, but for normatively “right” opinions! So in terms of your social standing, agreement with others is more important than truth. And when I get over my initial shock, I guess I can see why. It’s easier to form opinions than to find truth, and having agreement in opinions is thus an easy way to unite us. Or at least within that group, which will invariably have different opinions from other groups.

But truth is not necessarily a uniting force like that, since truth is entirely independent of whether or not we are in agreement about it. And the truth can hurt.

Nor can truth be altered for the sake of group conformity. The very act of altering truth undermines it. But if I change my opinion, I may very well find more connectedness. After all—so Bach says—opinions signal group loyalty. So the best thing you can do for yourself as a social animal is to optimize for agreement with your peers.

Ostracism

But the converse is also true. If you do not optimize for agreement with peers, chances are that the group you (want to) belong to, will not like you. I think that’s a sad truth, but it does seem to explain a lot experiences I’ve had. I often wondered—I know I am biased, but I think I am a nice, good person, I try to be as non-judgmental as possible, and I have some interesting things I can tell you about. So then why have I still struggled so much to be considered part of certain groups? Why did it seem people would come to me if they needed some knowledge or insight, but didn’t really include me socially?

When I was younger, I thought others felt I was intellectually intimidating. And that must have played some role, because I did hear from a few people that they didn’t understand much of what I said. But opinions we might share? How could they not understand that? Unfortunately for me, in my interactions with others, it’s facts and knowledge that tend to capture my attention—not the exchange of synchronized opinions. What I am fundamentally interested in is learning more about the world, rather than group conformity.

In most people, the fear of ostracism is

a greater force than the loss of meaning.[1]Fear of ostracism | Joscha Bach | Twitter

But I think it’s very helpful to realize this; that my values and interests don’t necessarily align with others. And that if being liked was important enough for me, I would know exactly what to do; I would drop my deep curiosity, and just signal to my peers that we are kin, simply by salivating over all the opinions we happen to share. Golly!

Instinct

Let me end this little article with a direct quote from Bach’s lecture, which may also plausibly show his autistic traits and values:[2]Joscha: Computational Meta-Psychology (2015) | YouTube

If you evolve an opinion-forming system in these circumstances [where opinions signal group loyalty], you should be ending up with an opinion-forming system that leaves you with the most useful opinion, which is the opinion of your environment. And it turns out most people are able to do this effortlessly…

They have an instinct that makes them adopt the dominant opinion in their social environment. It’s amazing, right?

And if you are a nerd like me, you don’t get this…

Post scriptum

I have to admit, I ultimately did not offer a satisfactory answer to the second part of the question I framed at the beginning. I considered writing more and doing comprehensive research to find various answers to this question, but I feared that would result in burnout before I got to publish the article. There is so much we are working on behind the scenes of Embrace Autism, that it’s sometimes challenging to find the time and energy to take on a big research project and bring an article to completion. I decided instead, to just write up a quick article to share something I learned and found to be useful with you. I might write a follow-up article with a more comprehensive answer in the future if you are interested.

Credits

This post was based on the part at 34:50–36:00 minutes of the video below, but I definitely encourage you to watch the whole video if you have the time and interest.

Comments

Let us know what you think!