Considering trauma and maltreatment are common among autistic people,[1]Trauma and Autism Spectrum Disorder: Review, Proposed Treatment Adaptations and Future Directions (Peterson, 2019)[2]Prevalence of co-occurring mental health diagnoses in the autism population: a systematic review and meta-analysis (Lai et al., 2019) and often occurs in our developmental years,[3]Traumatic Childhood Events and Autism Spectrum Disorder (Kerns, Newschaffer, & Berkowitz, 2015) I think it makes sense to have a look at the bond between parent and child during the child’s developmental years, and how the attachment style that results from this bond impacts us later in life.

In this article, we will have a look at attachment theory and the different attachment styles and their consequences with respect to cognitive, physical, and social-emotional development.

Disclaimer; refrigerator mother theory

Before we explore this topic, let me make a brief disclaimer and offer a bit of historical context. Although I will explore the consequences of disruptions in the bond between caregiver and child, I am in no way suggesting that autism is caused by this bond.

In his seminal paper on autism from 1943, Leo Kanner (1884–1981) called attention to what appeared to him as a lack of warmth among the parents of autistic children;[4]Autistic Disturbances of Affective Contact (Kanner, 1943) and in a later paper from 1949, he suggested autism may be related to a “genuine lack of maternal warmth”.[5]Problems of nosology and psychodynamics of early infantile autism (Kanner, 1949)

Kanner noted that the fathers rarely indulged in children’s play, and stated that from the beginning:[6]Problems of nosology and psychodynamics of early infantile autism (Kanner, 1949)

Children were exposed to parental coldness, obsessiveness, and a mechanical type of attention to material needs only…

They were left neatly in refrigerators which did not defrost. Their withdrawal seems to be an act of turning away from such a situation to seek comfort in solitude.

In a 1960 interview, Kanner even went as far as to describe parents of autistic children as “just happening to defrost enough to produce a child”.[7]The Child Is Father (Kanner, 1960) | TIME Bruno Bettelheim (1903–1990) promoted this psychogenetic idea of autism being a disorder of parenting, which became known as refrigerator mother theory.[8]Psychogenesis | The Autism History Project This theory has been thoroughly discredited, and it seems very likely—to me, it’s even obvious—that the coldness Kanner observed in the parents was his own reading of autistic traits in the parents.

But even though autism is definitely not caused by this parent–child bond, it can nevertheless have a significant impact on our behavior, sense of self, and cognitive capacities later in life. Parents don’t necessarily know what’s best for their child, and their own traumas can undermine their ability to meet their child’s needs. So let’s have a look at what happens when those needs aren’t—or indeed are—sufficiently met.

Attachment theory

John Bowlby (1907–1990) developed an evolutionary theory of attachment, which suggests that children are driven to form attachment bonds with their caregiver (the so-called attachment figure). The evolutionary reason behind this drive (called the attachment behavioral system) is that this will help the child to survive.

But the attachment style that develops can have both positive and negative consequences. Attachments are most likely to form with those who responded accurately to the baby’s signals, not the person they spent more time with. The more the attachment figure attends to the child’s needs, the more safety and trust the child will experience, as they develop a secure attachment. And once a safe haven has been established, the child becomes more secure in their autonomy, and starts exploring the world.[9]Attachment and Loss, Vol. I (Bowlby, 1969)

Conversely, when the child’s needs are not met, they will develop an insecure attachment, characterized by anxiety and avoidance.

Attachment styles

Mary Ainsworth (1913–1999) conducted experimental studies with infants—among them the so-called Strange situation studies—and identified four attachment styles:[10]Attachment, Exploration, and Separation: Illustrated by the Behavior of One-Year-Olds in a Strange Situation (Ainsworth & Bell, 1970)

- Secure attachment — The child feels trust and worthy of love, connect well and securely in relationships with others, and has the capacity for situationally appropriate autonomous action.

- Avoidant attachment — The child tends to avoid interaction with the caregiver.

- Ambivalent/resistant attachment — The child will feel concern that others will not reciprocate their desire for intimacy.

- Disorganized/disoriented attachment — The child will show overt displays of fear; contradictory behaviors that seem to lack goals or intentions; affects occurring simultaneously or sequentially; stereotypic, asymmetric, misdirected or jerky movements; or freezing and apparent dissociation.[11]Discovery of an insecure-disorganized/disoriented attachment pattern (Main & Solomon, 1986)[12]Procedures for identifying infants as disorganized/disoriented during the Ainsworth Strange Situation (Main & Solomon, 1990)

In the table below, I have compiled information about each attachment style and how the child responds to the departure of the caregiver, how they respond to a stranger in the room, and how they respond to the caregiver upon re-entry of the room.[13]Attachment, Exploration, and Separation: Illustrated by the Behavior of One-Year-Olds in a Strange Situation (Ainsworth & Bell, 1970)

Ainsworth’ attachment styles

| Attachment | Separation anxiety | Stranger anxiety | Caregiver return |

|---|---|---|---|

| Secure | The child will show some distress when their caregiver leaves. | The child may or may not be friendly with the stranger, but always shows more interest in interacting with the mother. | The child composes themselves quickly when the caregiver returns. |

| Avoidant | The child shows no distress during separation. | The child will often display maladaptive behaviors, avoids the caregiver, and will not explore very much regardless of who is there. | The child shows little emotion when the caregiver departs or returns. |

| Ambivalent | The child is often highly distressed when the caregiver departs. | The child will typically explore little, and is often wary of strangers, even when the caregiver is present. | The child is generally ambivalent when the caregiver returns (subtype C2: ambivalent), or may show displays of anger or helplessness towards the caregiver (subtype C1: resistant). |

| Disoriented | The child will show inconsistent behaviors and be uncoordinated with respect to achieving either proximity or some relative proximity to the caregiver. | The child may approach the stranger in an intrusion of desire for comfort, followed by losing muscular control and falling to the floor, overwhelmed by the intruding fear of the unknown and potential danger of the strange person. | 52% of disorganized infants continue to approach the caregiver, seek comfort, and cease their distress without clear ambivalent or avoidant behavior.[14]Parsing the Construct of Maternal Insensitivity: Distinct Longitudinal Pathways Associated with Early Maternal Withdrawal (Lyons-Ruth et al., 2013) |

And in the table below, you can see how each attachment style rates on the insecurity and proximity-seeking sub-scales of the Vulnerable Attachment Style Questionnaire (VASQ).

Attachment styles features

Etiology

In the table below, you can see the different causes of each attachment style; what has to go wrong in the caregiver–child bond for the child to develop one of the insecure attachments.[15]Attachment, Exploration, and Separation: Illustrated by the Behavior of One-Year-Olds in a Strange Situation (Ainsworth & Bell, 1970)

Attachment causes & effects

Interesting fact: Borderline Personality Disorder is strongly associated with the disoriented attachment style.[22]Borderline personality disorder and the search for meaning: an attachment perspective (Holmes, 2003)[23]Disorganized attachment and borderline personality disorder: a clinical perspective (Holmes, 2004)

A central problem is that disorganized attachment disrupts the construction of a unitary internal working model of the self and the attachment figure;[24]Disorganized attachment, models of borderline states and evolutionary psychotherapy (Liotti, 2000) instead, an internal working model of the self and of the attachment figure develops that is multiple, fragmented, and incoherent.[25]Procedures for identifying infants as disorganized/disoriented during the Ainsworth Strange Situation (Main & Solomon, 1990)

Consequences

When you develop an insecure attachment in childhood, this will have an effect on your cognitive, physical, and social-emotional development.

In the table below, I compiled a wealth of information I could find—though far from exhaustive—about both insecure attachment styles and their consequences.

Consequences of insecure attachments

Positive outcomes

When you have been securely attached in your developmental years, you are likely to feel a lot more confident and secure later in life. In the table below, you can see the positive outcomes of a secure attachment with respect to cognitive, physical, and social-emotional development.

Outcomes of secure attachment

Romantic compatibility

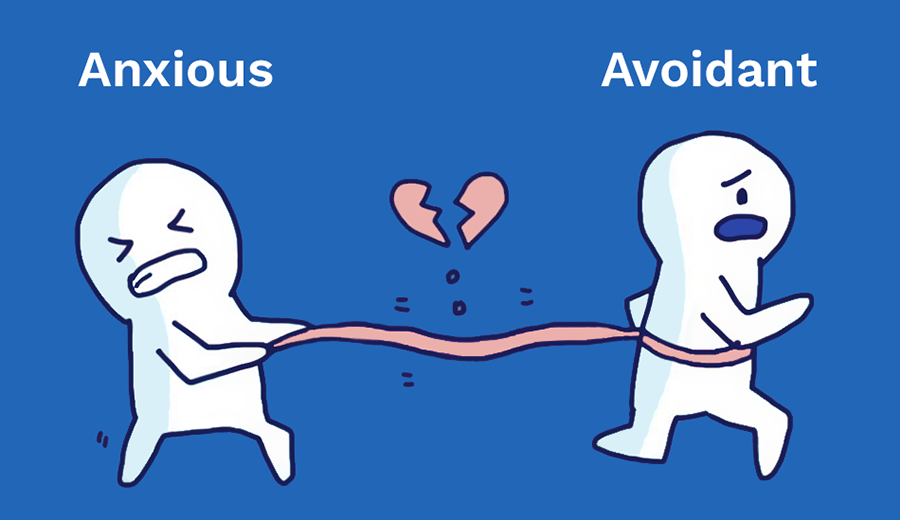

Lastly, I want to briefly discuss a few fascinating findings with respect to attachment style and partner selection. You would think people are most attracted to people with a secure attachment style, but not so! Research shows that people were most attracted to partners with similar attachment styles![198]Adult attachment, working models, and relationship quality in dating couples (Collins & Read, 1990)[199]Attachment Styles and Marital Adjustment among Newlywed Couples (Senchak & Leonard, 1992) So anxious people tend to date anxious partners—preferring them over secure and avoidant partners.[200]Adult attachment style and partner choice: Correlational and experimental findings (Frazier et al., 1996)

What I also find fascinating is that anxious individuals seemed particularly averse to avoidant partners.[201]Adult attachment style and partner choice: Correlational and experimental findings (Frazier et al., 1996) If you look at the Attachment styles features table in the Attachment styles section—and the Anxiety & avoidance table below—I think that makes a lot of sense, since anxiously attached people require a lot of proximity to their partners, while those with an avoidant style don’t deal well with a lot of proximity.

Anxiety & avoidance

At the same time, though, research also shows that nevertheless anxious women were dating more avoidant men, and anxious men were more likely to be with less secure women.[202]Adult attachment, working models, and relationship quality in dating couples (Collins & Read, 1990)[203]Influence of attachment styles on romantic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (Simpson, 1990) The reason being that their own attachment styles mutually confirmed their partner’s beliefs about the relationship; the avoidant partner is uneasy about commitment and too much intimacy, which are exactly the fears of the anxious partner; and for the avoidant partner, the distrust and demands for intimacy expressed by their anxious partner likewise confirms their expectations of relationships.[204]Attachment style, gender, and relationship stability: A longitudinal analysis (Kirkpatrick & Davis, 1994)

But your partner’s attachment style also informs your own evaluation of the relationship; both partners were less satisfied with their relationships when the man was avoidant or distant (rather than secure), and when the woman was anxious or preoccupied (i.e. with an ambivalent attachment).[205]Adult attachment, working models, and relationship quality in dating couples (Collins & Read, 1990) The table below gives an impression of how our views of ourselves and others inform how we relate to others.[206]Models of the self and other: Fundamental dimensions underlying measures of adult attachment (Griffin & Bartholomew, 1994)

Thoughts of self & others

And finally, not only do our attachment styles inform our partner choice, but the way we perceive our parents is also of influence—especially the way we see our mothers. For example, people who rated their mothers as more cold and ambivalent were less attracted to secure partners.[207]Adult attachment style and partner choice: Correlational and experimental findings (Frazier et al., 1996)

So it seems that we actually learn to be comfortable with our attachment style—even if it’s an insecure one. Developing an insecure attachment style is no fun; but once in place, it seems that on some level we regard that insecure attachment as a place of comfort. It may be dysfunctional and toxic, but at least we know what to expect. I find it quite amazing that the attachment style we develop ultimately defines who we are compatible with, and what kind of partner we are likely to choose.

There is a known psychological principle that says we are more likely to select partners based on our childhood wounds, so that through interacting with them, we can come to resolve our traumas. And I think that is what we are seeing here as well.

Curious whether you have an insecure attachment?

Take the Vulnerable Attachment Style Questionnaire:

Comments

Let us know what you think!