Bright stars and black holes: what it means to

receive an autism diagnosis later in life

A harsh reality and a twinkle of hope

Many of us remember when we were first diagnosed with autism. For me, it was as recent as this past summer. I experienced a great sense of relief: “It’s not my fault,” was my first thought upon diagnosis. I realized much of what I’d intuited as personal failing was just a different way of seeing the world. So, I often wonder what this self-realization means for those who are undiagnosed autistics.

Positive self-realization is the topic of a study published this month in the journal Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine. Co-authors David D. Stagg, Ph.D. and Hannah Belcher interviewed 9 autistic adults who received their autism diagnoses in midlife.[1]Living with autism without knowing: receiving a diagnosis in later life

Before we dive into the study, if you wondered if you may be on the autism spectrum, I recommend checking out this post:

How do I know if I’m autistic?

A star is reborn

The nine interviewees were recruited from ads on autism support forums and Belcher’s blog. All interviewees’ ages ranged from 52–54. Five were female and four were male. All except two of the interviewees received their autism diagnosis within two years of the study. Seven of the nine were married and most had children. Most were employed although one was retired, and another was unemployed. The interviewees were given pseudonyms to protect their identities.[2]Living with autism without knowing: receiving a diagnosis in later life

The co-authors took care to offer a variety of ways to conduct the interviews. While most opted to meet face-to-face, one was interviewed via Skype video calls, and another by long email exchanges.[3]Living with autism without knowing: receiving a diagnosis in later life Such study design not only ensures people aren’t left out due to struggles with social anxiety, it demonstrates a respect for the individuals themselves by honoring their preferred methods of communication

The interviewees largely found that their diagnoses positively affected their lives. Learning that they’re autistic meant they could start to understand themselves and their behaviors as an innate and expression of their neurophysiologies.

When a star dies, the intense and brilliant crescendo that is a supernova forms a new star composed of familiar elements. They don’t truly die, in fact, but are reborn. Such is true in the case of autistics who are reborn through the self-realization that comes with a diagnosis.

Linda: Since my diagnosis it’s been fantastic. It’s a breakthrough for me now to… Somehow, it’s helped me start to tick off emotions. I’ve realised what these feelings are that I have … I’ve identified a couple of months ago, guilt. For the first time I’ve realised what guilt feels like, and I can look back on my life and see all the times I’ve felt guilty but didn’t know … Yes. It was a revelation. Fantastic.

David: Now I know that allegedly if you’re just, you don’t like bright light, allergic to it. I don’t know, it’s like I have explanations for things now, I never used to have.

Paul: Being aware of it [ASD] has enabled me to plan and prepare for situations, knowing how I may react, and how to avoid difficult situations … so I can keep to places and activities I am comfortable with.

Brenda: It really was like a sort of eureka moment … it was kind of a relief … and it wasn’t my fault, and that was one of the biggest things, that I realised it wasn’t my fault.

Mary: So it was a real (sighs) I mean ‘revelation’ is not even the word, really, it was (sighs) I was just stunned, really, to think that I could have gone through life potentially having Asperger’s and never having realised.

Indeed, these words punctuate the overall experience of receiving a diagnosis: revelation, relief, and understanding.

Methods ensuring autistic experiences are valued

A remarkable feature of this study is that it was conducted by an openly autistic person. Ms. Belcher, currently a Ph.D. candidate, deviates from a trend in autism research that largely ignores the phenomenological perspective of autistics. In short, researchers have not spent enough time creating studies that allow autistic research participants to express how they experience the world.

Belcher has appeared on the BBC to touch on this underdiagnosis issue:

The authors were aware of potential bias. To avoid such bias, the authors followed the free-associative narrative approach. This approach asks general questions aimed at guiding the interviewee to share their phenomenological perspective—their first-person experience of the world.[4]Living with autism without knowing: receiving a diagnosis in later life

The narrative interview technique allows the interviewee to guide the direction of the interview, thus allowing the focus and agenda of the interview to change depending on the interviewee’s own experience. In this respect, we attempted to avoid imposing a narrative on the interviewee, which may occur through overly directive questioning.

Perhaps instead of asking what it’s like to be a bat, we should ask what it’s like to be neurodiverse.[5] Mary Bates Ph.D. Animal Minds What Is It Like to Be a Bat? | Psychology Today[6]What Is It Like to Be a Bat? | Thomas Nagel[7]Does Peer Rejection Moderate the Associations among Cyberbullying Victimization, Depression, and Anxiety among Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder?

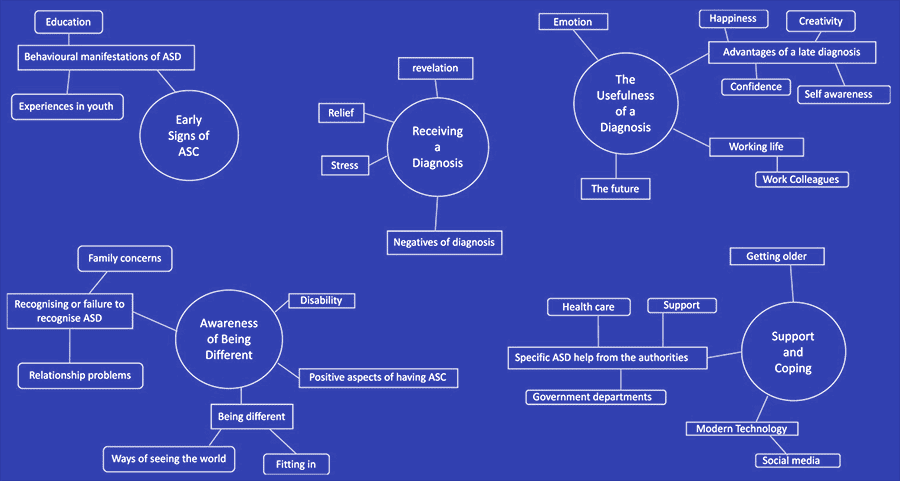

The diagram below shows how the five main themes of the interviewees’ answers correspond semantically. To avoid biasing the results, the authors used NVivo, a coding software that finds semantic links using interview transcripts.[8]Living with autism without knowing: receiving a diagnosis in later life

The questions interviewees were asked:

- When did you receive a diagnosis?

- When did you first become aware you had autism?

- Tell me how managing your autism has changed as you have grown older.

- How has the diagnosis affected your life?

- How does your autism impact on your daily life?

- Tell me about the positive aspects of having autism?

- Are there negative aspects?

- Tell me about your future hopes and fears

- Do you currently have a job? Can you tell me about your work?

If you are (or believe you are) on the autism spectrum, then it may benefit you to ask yourself these questions.

Black holes and revelations

Being autistic can sometimes feel like being stuck at the event horizon of a black hole. Unable to escape, the immense forces of societal pressures, rejection, and loneliness consumes you. Although the interviewees found the diagnoses to be mostly positive, receiving a diagnosis may lead to painful experiences. Autism is still stigmatized and as such autistic people suffer rejection and discrimination professionally and in their private lives.[9]Neurotypical Peers are Less Willing to Interact with Those with Autism based on Thin Slice Judgments[10]Social stigma contributes to poor mental health in the autistic community

The interviewees recounted their own experiences of the proverbial black hole:

Brenda: I’d always felt like this alien… I feel like I’m a different type of human to non-autistic humans.

James: I just didn’t fit in, and I felt terrible.

Perhaps most upsetting is that autistic people will often see their social misunderstandings as personal defects.[11]Living with autism without knowing: receiving a diagnosis in later life

David: I just thought I was just bad really and didn’t really fit in and people didn’t like me, and I couldn’t really understand why. I suppose I thought I was different but wrong but didn’t understand what was wrong.

Brenda: I thought maybe I’m a bad person, I’ve got a horrible personality, there’s something about me people don’t like, and I didn’t understand why.

For some of the interviewees, a diagnosis lowered their self-esteem. Notably, the feelings of despair are associated with perceiving oneself as othered. Feelings of fundamental differentness, codified and set in stone via diagnosis, brings to the forefront of the newly-diagnosed the harsh reality of being different. This makes perfect sense when one considers how non-autistic peers often misunderstand and ostracize autistic people.[12]Neurotypical Peers are Less Willing to Interact with Those with Autism based on Thin Slice Judgments However, this isn’t to say that diagnosis is itself the issue, rather, the attitudes pertaining to autistics is the source of this alienation.

Brenda: It robs me, I guess, of maybe confidence and stuff. Maybe I would have, if I hadn’t got it, I would have maybe done some different things in my life.

Mary: It’s been really difficult to maintain a feeling of sense of worth.

And for James, the negative effects of being diagnosed were most poignant.

James: She [his employer] started bullying me quite seriously from then on, and within about eighteen months I was out of a job, and I think if I hadn’t bothered finding out what Asperger’s was, I would have just been this lonely person who just carried on. I sometimes wonder whether I should have, is it a bad thing to have had, the diagnosis.

Caution: As James’ experience highlights, openly discussing your autism diagnosis may lead to discrimination. Please be careful to take into account who you’re telling about your diagnosis and what the repercussions may be.

James’ account gives credence to the argument that it’s not autism itself that is so detrimental to life outcomes, but the stigma associated with diagnosis—the othering (the reductive action of labeling and defining a person as a subaltern native). Indeed, he felt that his diagnosis led to discrimination at his workplace, which resulted in the loss of his job. Robert then goes on to explain how there aren’t many supports for autistic adults. This sentiment was largely shared by the other interviewees.[13]Living with autism without knowing: receiving a diagnosis in later life

Robert: There’s none, there’s none you know there’s none that is positive you know it, the support that’s out there, except for voluntary groups and people that you meet on Twitter and so on, the support [for autistic adults] that’s out there is couched in this mental health you know, mental illness sort of framework.

Other interviewees share Robert’s frustrations about the lack of support.

Debra: I did have a consultant psychiatrist, and the one time when I was really bad, around Christmas time, I contacted him and he never got back to me.

Susan: I am thinking this autistic spectrum condition might just be phased out soon because it’s too expensive to recognise, that’s what I am wondering.

Linda: I registered as disabled, but then … I don’t know what point that’s … They just sent me back a card. It didn’t even have my name on it. Maybe anyone can write in for a disabled card.

Acceptance overcomes the gravitational pull of isolation

The negative views that pervade the public conversation on autism are having harmful effects on autistic people. The interviewees’ responses show that even though they personally benefitted from an autism diagnosis, the negative perceptions of autistic people by their non-autistic peers results in lower self-esteem, alienation, and discrimination. The silver lining in all of this is that it’s shown how important self-advocacy and community are for those of us on the spectrum. The authors note

When help was received, the interviewees reported that it often came from within the ASC [an abbreviation of autism spectrum condition, an alternative phrase to ASD] community and through online ASC support groups.

It seems obvious that an understanding and accepting community would alleviate the pain of isolation. But it appears that governments and societies have yet to come to this realization as it pertains to autism. Ultimately, this research shows how important it is for autistics to be accepted and embraced rather than rejected and belittled. And, as our blog’s name implies, embracing autism is what we strive to do.

We must support each other and resist the pull of the black hole that is the embodiment of our struggles. After all, it takes many stars to form a galaxy.

For further reading on getting a diagnosis as an adult, have a look at:

Comments

Let us know what you think!