When coordination or movement is affected, the culprit is almost certainly a person’s little brain. No, I’m not being demeaning. Everything to do with motor control (precision, coordination, and timing of movements) is done by the cerebellum, which is Latin for little brain.

So in this post, let’s have a look at the differences in the cerebellum of autistic people and those with related conditions.

Cerebellum

The cerebellum is a structure at the back of the brain (above the brainstem), as you can see in the diagram below.

The cerebellum plays an important role in motor control, which is the clinical term for the regulation of movement.[1]Consensus paper: the cerebellum’s role in movement and cognition (Koziol et al., 2014)

But the cerebellum does not initiate movement (the motor cortex does that); it uses information from sensory systems (vision, hearing, touch, taste, smell, and balance) to compare the performance of a given movement with the original intent of the brain. So if needed, the cerebellum corrects actions to maintain coordination, precision, and accurate timing.

Motor differences in autism

In autistic people, certain differences in the cerebellum can cause impairments/alterations in the maintenance of posture, balance, motor dexterity, and coordination of movement.[2]Motor Coordination in Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Synthesis and Meta-Analysis (Fournier et al., 2010)

Up to 80% of autistic children show differences in motor coordination,[3]Autism spectrum disorder and the cerebellum (Becker & Stoodley, 2013) and somewhat surprisingly, the extent of challenges in motor coordination correlates not only with the extent of autism traits, but inversely correlates with IQ as well.[4]Impairment in movement skills of children with autistic spectrum disorders (Green at al., 2009)

In a study from 2009, Dido Green et al. studied 101 autistic children (aged 10–14), as well as children with broader autism phenotype (BAP), and found that:[5]Impairment in movement skills of children with autistic spectrum disorders (Green at al., 2009)

- 79% had definite challenges with movement.

- 10% had minor challenges with movement.

- Autistic children had more motor problems than those with BAP.

- Children with an IQ less than 70 had more motor challenges than those with an IQ above 70.

A study from 2011 by Claudia List Hilton et al. based on 67 families with autism reported very similar findings:[6]Motor impairment in sibling pairs concordant and discordant for autism spectrum disorders (Hilton et al., 2011)

- 83% of autistics scored at least one standard deviation below the general population mean on total motor composite (compared with 6% in non-autistic siblings).

- Motor skills were substantially lower in autistic children, but were essentially normal in their non-autistic siblings.

- Motor skills were highly correlated with autistic traits and IQ.

Motor control challenges were even found to be one of the first signs of the autism phenotype in infants,[7]Gross Motor Development, Movement Abnormalities, and Early Identification of Autism (Ozonoff, 2007) meaning this is one of the first things to look for in infants when it comes to identifying autism.[8]Analysis of unsupported gait in toddlers with autism (Esposito et al., 2011)[9]Early identification of autism spectrum disorders (Zwaigenbaum, Bryson, & Garon, 2013)

It has even been suggested that dyspraxia—a form of developmental coordination disorder (DCD) which affects fine and/or gross motor coordination—is a core feature of autism, rather than co-occurring.[10]Dyspraxia in autism: association with motor, social, and communicative deficits (Dziuk et al., 2007)[11]Specificity of dyspraxia in children with autism (MacNeil & Mostofsky, 2012)

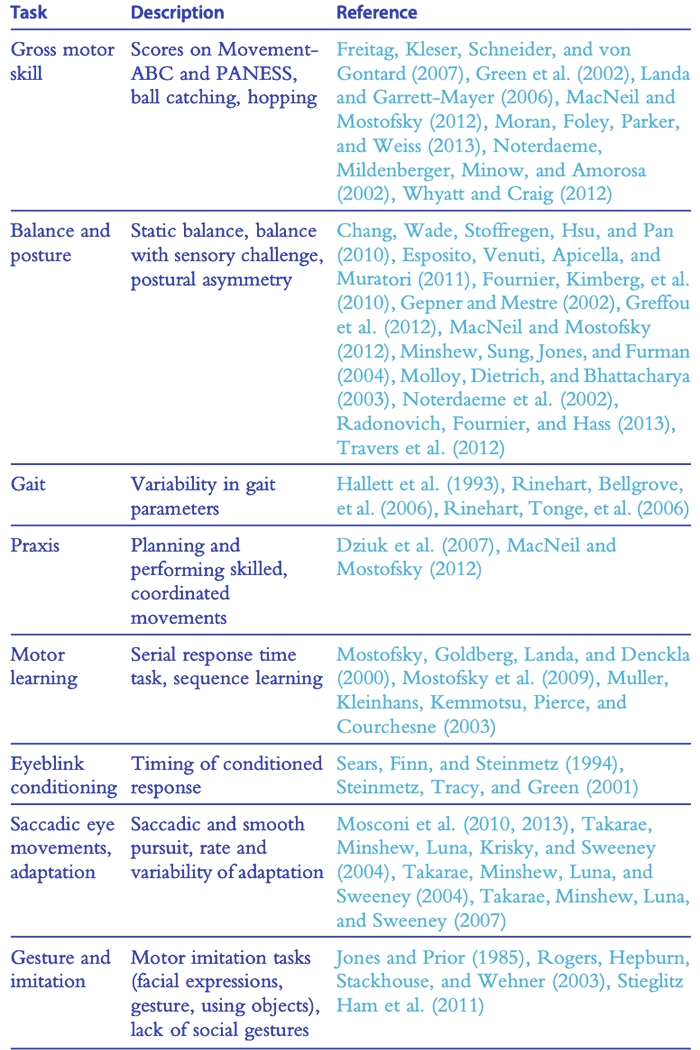

In the table below, you can see the various motor differences in autism due to the cerebellum:[12]Autism spectrum disorder and the cerebellum (Becker & Stoodley, 2013)

So let’s have a look at some of the specific motor differences common in autism.

Balance & orientation

A study from 2003 by Cynthia A. Molloy et al. shows differences in the vestibular system in autistic people, which means we tend to have challenges with our sense of balance (called equilibrioception) and spatial orientation.[13]Postural stability in children with autism spectrum disorder (Molloy, Dietric, & Bhattacharya, 2003) And of course, both these things have an effect on general movement as well. Limbs might for example sort of wander around in space without the person necessarily being aware of it.

What I believe relates to this is the use of hand gestures, or lack thereof. I personally am unable to “talk with my hands”, by which I mean using hand gestures to emphasize or otherwise complement what I say. I have also seen videos of autistic people who do use hand gestures, but it looks forced and uncoordinated. I got the impression that the use of hand gestures was non-intuitive, so the people in the videos had to try to concentrate on making the correct hand gestures in accordance to what they’re saying, AND make it all synchronize. I am impressed they managed to do this at all, because it’s a lot to have to focus on while also talking and thinking. And I’m quite fascinated by the fact that the use of hand gestures while talking is intuitive to many other people.

By the way, research from 2010 by Heidi Stieglitz Ham et al. shows that for autistic people only, there is a relationship between recognition and interpretation of pantomimes (i.e. gestures that describe object use). So unlike non-autistics, it seems we have difficulty imitating gestures when we don’t recognize them, which I imagine would also undermine our ability to use hand gestures in conversation.[14]Exploring the Relationship Between Gestural Recognition and Imitation: Evidence of Dyspraxia in Autism Spectrum Disorders (Ham et al., 2011)

When it comes to balance, I don’t believe I experience any issues as an adult, although I don’t truly know how my sense of balance compares to others. I have enough balance that I don’t randomly topple over, which is sufficient balance for me. But when I was younger, things were quite different. When I was 8 or so, I practiced Judo for a while to get a better sense of balance. I remember practicing really basic things such as somersaulting, and focusing hard on getting it right. Most of the time I couldn’t do the somersault straight.

As a kid, I did a lot of therapy and gymnastics classes to practice motor control.

Motor skills

A study from 2007 by Christine M. Freitag et al. indicates differences in gross motor skills and fine motor skills, with challenges in the ability to remain balanced while engaged in movement (called dynamic balance), and the ability to make opposing movements in quick succession (called diadochokinesis).[15]Quantitative assessment of neuromotor function in adolescents with high functioning autism and Asperger Syndrome (Freitag et al., 2007)

Personally, as a child I had a lot of challenges with gross motor skills; as I just described, movements such as hopping and somersaulting gave me a lot of challenges due to issues with balance and coordination. But I’ve experienced a few issues with my fine motor skills as well.

Until the age of 12 or so—maybe longer—I frequently spilled over glasses while pouring drinks, or dropped them. And each time I would be in hysterics. “It happened again!” But beyond that, I think my fine motor skills have been alright.

There were even some things involving fine motor skills that I excelled at, such as drawing/illustrating. I don’t know if I had the talent to start with which made me enjoy it so that I would do it a lot, or I enjoyed doing it so I did it a lot and became good at it. I suspect there is some innate talent—artistic/creative genes seem to run in the family—but I am quite convinced practice took a big part of it. Either way, when other kids my age were still drawing simple stick figures, I was already focused on drawing fingers and limbs with volume.

Coordination

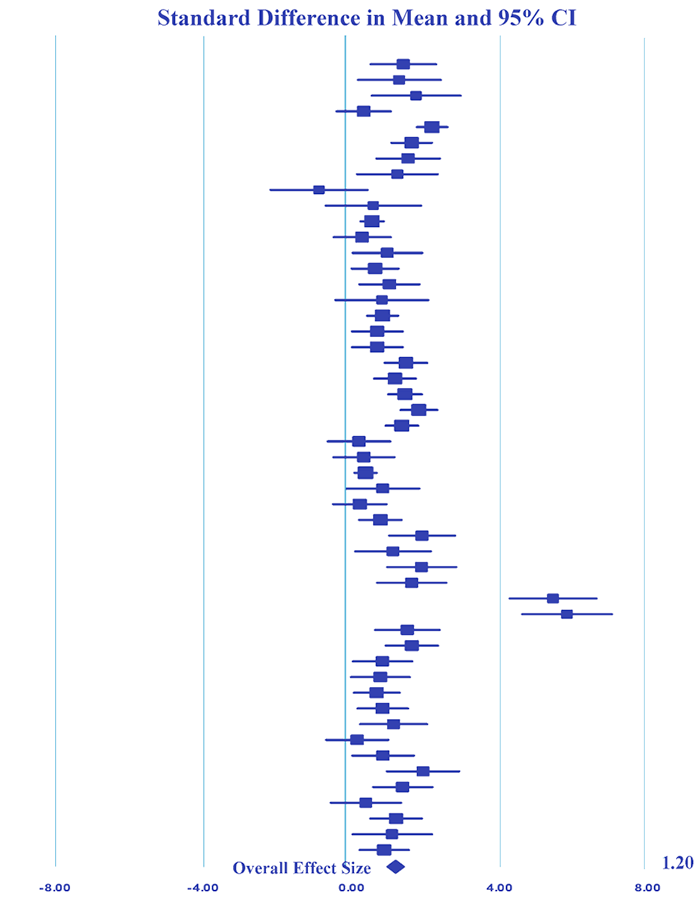

A meta-analysis from 2010 by Kimberly Fournier et al. also indicated significantly lower motor abilities in autistic people compared to controls. In the forest plot below, you can see all 51 studies on this place autistic people on the right side of the line; 0 means no difference, and anything above that means worse motor coordination than controls. The average mean difference based on all 51 studies was 1.20.[16]Motor Coordination in Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Synthesis and Meta-Analysis (Fournier et al., 2010)

The paper also looked into possible motor differences depending on autism classification, and found that regardless of whether the participants were classified as autistic, ASD, or Asperger’s syndrome, they all showed challenges in motor coordination:

- Autism (696 subjects) — a mean difference of 1.28.

- ASD (176 subjects based on 10 studies) — a mean difference of 1.13.

- Asperger’s syndrome (73 subjects based on 6 studies) — a mean difference of 0.939.

So this study suggests those classified as Asperger’s have fewer coordination problems than those classified as autistic (according to the old paradigm before all autism conditions were generalized as ASD), but they still have significantly more challenges.

In my case, I continue to have problems with coordination even as an adult. The bottom of my legs seem almost perpetually bruised, and generally, I don’t even know how, when, or where it happened. In the picture below, you can see what my legs looked like on 4 January. Notice both the bruises and older wounds.

And below you can see my left leg 22 days later, on 26 January. This time it wasn’t my fault though. The corner of the table jumped right in front of me as I tried to make my way through the living room. Don’t worry, I disciplined him well by giving him a time-out by putting him in the naughty corner. Also, notice in the left picture the same wounds as in the previous picture—now almost healed, which provides a nice clean canvas for new wounds. That is the art of autistics walking.

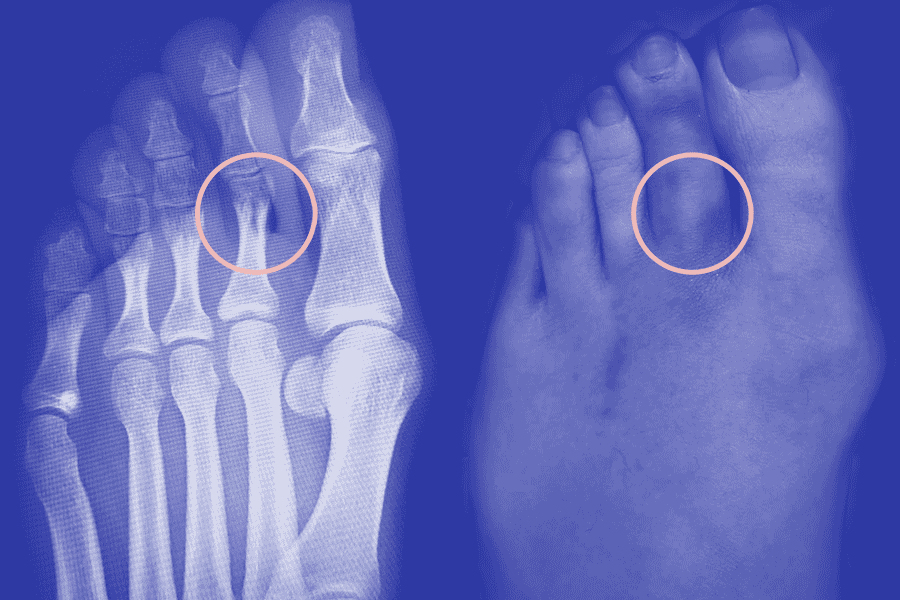

I also hit my toes quite frequently as I walk into tables and such. In 2019, I fractured two toes on different occasions. Below is my X-ray of the first fracture.

Interestingly, as far as I recall I haven’t walked into things at night when the house is dark. I think the low vision in the dark urges me to be more careful (more mindful, really) of where I walk. An autistic friend said he relies more on his memory of the layout of the house in the dark, so it’s interesting we may use different methods to achieve the same thing: avoid walking into things in the dark. Then why does it have to be so difficult sometimes during daylight?

All of this thanks to our dear little brain.

For more information on the cerebellum and

anatomical brain differences, have a look at:

Comments

Let us know what you think!