As a result of the neurodiversity movement which emerged in the late 90s,[1]Neurodiversity – On the neurological underpinnings of geekdom | The Atlantic the perceptions of autism in the public eye started to take on a more positive form; autism started to be seen as a condition characterized not only by impairments, but as a multi-faceted condition with both strengths and challenges.

It is through this acknowledgment that autism can be seen as more than a disorder. It’s more appropriate to think of autism as an Autism Spectrum Difference.

Ways of seeing

Judy Singer, an Australian sociologist diagnosed as autistic and one of the pioneers of the neurodiversity movement noted that the neurologically different represent a new addition to the familiar political categories of class, gender, and race, and will augment the insights of the social model of disability.[2]Why can’t you be normal for once in your life? | University of South Wales

Singer further states that even assumptions about perception which we tend to take for granted—that we all more or less see, feel, touch, hear, smell, interpret, process, and broadly speaking experience in more or less the same way unless visibly or otherwise obviously disabled—are dissolving.[3]Why can’t you be normal for once in your life? | University of South Wales For this reason, the neurodiversity movement must keep gaining traction, so that differences in the human condition can be more readily acknowledged, explored, and even utilized.

We all experience reality not as it truly is, but filtered through our sensory input. This filtered reality is called the phaneron. Now, autistic people have been shown to filter out less (arguably redundant) sensory information.[4]Brain anatomy and sensorimotor gating in Asperger’s syndrome[5]Sensorimotor Gating Deficits in Adults with Autism This neurological filtering process is called sensory gating. So you might argue the experience of reality of autistic people is more “pure”—more unadulterated, which may be why we are more prone to (sensory) overwhelm. Imagine all that information that neurotypicals filter out. Yes, they call it redundant information, but might it be that neurotypicals deem certain information redundant simply because their brains inevitably filter that information out? How then could you deem that information anything other than redundant—assuming you even register it in the first place?

But even if—or assuming—the sensory experience of autistic people is broader and deeper, we are inevitably constrained by our human senses. It’s interesting how our senses shape our reality, while at the same time establishing the boundaries of subjective reality to which we have access. Think for example of a blind person, where one sensory experience is absent and thus plays no role in their subjective reality. To better understand how our subjective reality is constrained, think of animals with senses we don’t have—such as magnetoreception—and how that adds to their experience.

It’s surprising how narrow our experience of reality is. Never mind about the senses humans don’t possess. The senses we do possess are limited as well. Compared to an eagle, our perception is weak, but even if we had eagle eyes, it’s only a small part of the electromagnetic spectrum that is the visible spectrum—the light humans can see. The typical human eye responds to wavelengths of approximately 380–740 nanometers, whereas the entire electromagnetic spectrum ranges from 1 picometer (0.001 nanometers) to 100,000 km. If that doesn’t say much, the visible spectrum is only 2.3% of the entire electromagnetic spectrum on a logarithmic scale, and 0.0035% on a linear scale! But with various detectors, we can absorb gamma rays, X-rays, ultraviolet, infrared, microwaves, and radiowaves, and convert those signals to the visible spectrum, and new worlds open up; by doing this, we can see parts of the universe we couldn’t see before.

Similarly, with the unique experiences and perceptional and cognitive abilities that neurodivergent individuals have, it seems this is a rich and largely untapped source of information; they can offer insights into the human condition and perhaps even reality itself. Potentially, neurodivergent people can experience aspects of reality which neurotypicals may not be able to access. I’m sure neurotypicals experience reality in ways I cannot grasp as well. This should be celebrated. We should more readily investigate the experiences of others!

Autistic perception

Let’s highlight a few differences in the perception of autistic people so you get a better understanding of how the autistic experience is richer in some ways and less rich in other ways compared to neurotypicals and non-autistics. This is not an exercise in autistic glorification, but an attempt to highlight the differences and potentials of neurodiverse people. A similar showcase can be constructed for other neurodivergent conditions (and indeed neurotypicals as well), and I do hope people share those as well and compare! There is a lot we can learn by looking at our differences, and appreciating them for what they are.

In a paper from 2001, researchers Laurent Mottron and Jacob Burack proposed the enhanced perceptual functioning model (an alternative to the weak central coherence model), which outlines eight principles of perception in autism.[6]Enhanced perceptual functioning in the development of autism (Mottron & Burrack, 2001)[7]Enhanced Perceptual Functioning (Mukerji, Mottron, & McPartland, 2013)

The enhanced perceptual functioning model has since been updated, so rather than list the eight principles from the original paper, let me list a revised version from a 2006 paper by Laurent Mottron and Michelle Dawson et al., based on 5 years of research:[8]Enhanced Perceptual Functioning in Autism: An Update, and Eight Principles of Autistic Perception (Mottron, Dawson, & Soulières et al., 2006)

- A more locally-oriented visual and auditory perception.

- An increased gradient of neural complexity, which is inversely related to the level of performance in low-level perceptual tasks.

- Early atypical behaviors have a regulatory function toward perceptual input.

- Perceptual primary and associative brain regions are atypically activated during social and non-social tasks.

- Higher-order processing is optional in autism and mandatory in non-autistics.

- Perceptual expertise underlies Savant Syndrome.

- Savant syndrome is an autistic model for subtyping PDDs.

- Enhanced functioning of primary perceptual brain regions may account for autistic perceptual atypicalities.

We are currently working on a post on autistic perception where we will explain what all of this means. Meanwhile, on our Powers & Kryptonites page you can find more aspects of autistic perception that differ:

Powers & Kryptonites

Neurodivergents needed

As the neurodiversity movement has gained traction and awareness of various neurodivergent conditions increases, companies are starting to hire neurodivergent individuals specifically for their specialized talents.

For example, in 2015 Microsoft created an Autism Hiring Program to attract talent in what they consider to be untapped potential in the marketplace. Having said that, their program may ironically not be the most diverse, at least in terms of PR and the exclusion of certain demographics therein.[9]I’m Autistic, and I Don’t Support the Microsoft Autistic Hiring Program | Shaun Bryan | Medium But hey, it’s good to see big companies are making an effort to be more inclusive of neurodiversity.

Two years before that in 2013, the international information and communication technology consulting firm Auticon started, which exclusively employs autistic people, and currently has more than 150 employees.[10]The firm whose staff are all autistic | BBC

In 2017, the police in The Hague in the Netherlands started hiring autistic people to analyze security camera footage to identify suspects and evidence.[11]Camerabeeldspecialist: Autisme geen beperking maar kwaliteit bij politie-eenheid Den Haag | Hulpverleningsforum Because of their exceptional ability to concentrate and attention to detail, these autistic detective employees analyze and identify precisely those images that can be crucial in an investigation, way faster than their neurotypical colleagues. In 2018, the organization of autistic people that worked with the police force AutiTalent, won the Cedris Waarderingsprijs (Cedris Appreciation Award).[12]Haagse politie wint prijs met autistische camerabeeldspecialisten | Omroep West[13]Autitalent wint Cedris Waarderingsprijs | Cedris

And obviously, autistic people are not the only neurodivergent people that companies are starting to look for. While dyslexia is characterized by processing issues that affect reading and writing, when it comes to interpreting letters and symbols, they are also highly creative, intuitive, and excel at three-dimensional problem solving and hands-on learning. So the specialized minds of dyslexic people can be utilized in various ways. For example, given their spatial abilities, some architecture firms hire predominantly dyslexics, and many famous architects in the world are dyslexic.[14]Richard Rogers, Architect | The Yale Center for Dyslexia & Creativity

Also, the British Intelligence Agency uses dyslexics’ ability to analyze complex information in a “dispassionate, logical and analytical way” in the fight against terror, and as of 2014, they have employed 100 dyslexic and dyspraxic spies.[15]GCHQ employs more than 100 dyslexic and dyspraxic spies | The Telegraph

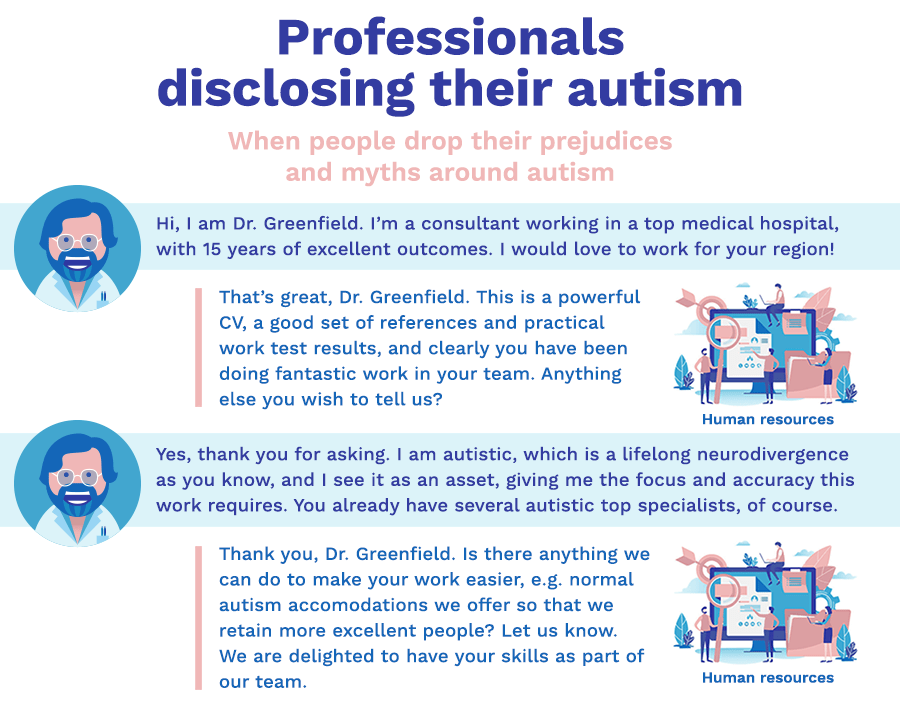

So the neurodiversity movement aids in the recognition of neurodivergent people’s particular talents, skills, and traits, which in turn helps improve work environments. For example, Ann Memmott presents a case of a hospital that had excellent autistic medical professionals who were concerned to say they’ve always been autistic. The new HR teams wanted to stop it from being a culture of fear. This is what good HR looks like, and these kinds of attitudes are made possible by the neurodiversity paradigm:[16]Professionals disclosing their autism | Ann Memmott | Twitter

United under neurodiversity

What is so wonderful about the neurodiversity movement is that it sees all people in terms of their unique functioning and subjective experience. Based on that mindset, people are more readily respected as individuals in their own right, because all forms of neurodiversity are seen as valuable under this framework, and should be respected as a natural form of human variation.

The pathology paradigm, on the other hand, risks being a judgmental mindset, where everyone is compared to a baseline of normal functioning, and anything that deviates from that ought to be corrected. This mindset may be understandable when considering people that are suffering, but we must be careful not to overlook or ignore the experience of the individual.

Although neurodiversity is not without controversy, I hope people will ultimately unite under the neurodiversity banner, rather than use it to get deeper entrenched into tribalism. Because the neurodiversity paradigm is—or ought to be—all-inclusive. As you can see in the Euler diagram below, neurodiversity comprises all of us, with a smooth transition between neurotypicality and atypical neurology.

Although there is a threshold where you qualify for or are excluded from a certain diagnosis, the terms you see here are just discrete categories we use to model and approximate a complex multidimensional spectrum that constitutes human diversity.

For example, people with broader autism phenotype (BAP) have personality and cognitive traits that are similar to but milder than those observed in autism, and possibly depending on the diagnostician may or may not qualify for an autism diagnosis. So while these people fall somewhere on the autistic spectrum, they may instead be classified as allistic. Note also that the allistic category both includes neurotypicals and has overlap with neurodivergent/atypical neurology.

Who is neurotypical?

We assume the population mostly consists of neurotypicals, but is this actually true? Below I have listed a few statistics of various neurological conditions and personality disorders.*

- Autism: 1–2.6%[17]Global prevalence of autism: a mini-review

- ADHD: 5.29%[18]ADHD prevalence estimates across three decades: an updated systematic review and meta-regression analysis

- Schizophrenia: 0.48%[19]An evaluation of variation in published estimates of schizophrenia prevalence from 1990─2013: a systematic literature review

- Dyslexia: 7%[20]Seminar: Developmental Dyslexia

- Personality disorders: 4.4−21.5%[21]Population prevalence of personality disorder and associations with physical health comorbidities and health care service utilization: A review

This very incomplete list already totals a neurodivergence prevalence of 18.17–36.87%. So that means that approximately 63–82% of the world population is neurotypical, and it may be substantially less depending on how many conditions you include in the neurodiversity framework, and at what thresholds for the various conditions you measure.

So yes, neurotypicals are still the majority. Of course, this would necessarily be the case, as neurotypicality is normative neurology. But honestly, even at a prevalence of 18%, that’s 1 billion 386 million neurodivergent people walking on this planet! Think of all those different perspectives and experiences! Think of the collective expertise and insights these people can bring!

- Research from the Karolinska Institute from recent years indicates personality disorders are mostly hereditary rather than trauma-based as we originally thought (remember how historically we have been through the same considerations with autism?), and so a paradigm shift is underway; in line with the neurodiversity movement, personality disorders are now also starting to be seen as a natural neurological variance.

Fix what?

Do we really want to “fix” over a billion “broken” people, or are we ready to see their neurological variance as a natural function of nature, which may just be conducive to society? It would be particularly conducive to society if it were shaped under some of the principles of the neurodiversity paradigm. Because if society is more inclusive and accommodating, more people can contribute to it.

And let’s not forget that a person is disabled not by their impairment, but by the failure of their environment to accommodate their needs.[22]Understanding disability: From theory to practice This is not to say that all impairments can be resolved by providing a more accommodating environment,[23]Neurodiversity: An insider’s perspective but indeed many impairments emerge out of the mismatch between people’s needs and what society offers. A good society makes good people make a good society…

Perhaps then we ought to address issues in our environment in an attempt to accommodate more people and ameliorate more impairments, rather than trying to address perceived issues in our fellow people on an individual basis—often through extensive psychotherapy and prescribing psychotropic drugs.

Do we sustain our environment and reject the people for whom that environment is lacking (exclusion), or do we change our environment and (truly) welcome humanity in its diverse manifestations (neurodiversity)?

Comments

Let us know what you think!