There once was a man, who would almost certainly be classified as autistic nowadays, or as Asperger’s syndrome up until seven years ago.[1]Did Ludwig Wittgenstein have Asperger’s syndrome? (Fitzgerald, 2000) But in his time, Asperger’s syndrome wasn’t yet a diagnostic classification. He was born one month and four days short of a full century before I was born, after all.

He had five elder brothers, who likely shared autistic traits (as siblings tend to do[2]Sibling Recurrence and the Genetic Epidemiology of Autism (Constantino et al., 2010)[3]Subgrouping siblings of people with autism: Identifying the broader autism phenotype (Ruzich et al., 2016), the eldest of whom was a musical prodigy). Three of his brothers sadly ended up dying by suicide: the eldest, Hans, at 25; the 3rd eldest, Rudi, two years later at 22; and the 2nd eldest, Kurt, sixteen years later at 44.

He himself fortunately didn’t follow the same path as his three eldest brothers. But he thought about suicide for much of his life. His psychiatrist described him as a “depressed and sad man” who was “down with depressed affect” and “gloomy”. The afternoon after his 62nd birthday, he went for a walk, and became very ill that evening; when his doctor told him he might live only a few days, he replied, “Good!”

The man I’m talking about is Ludwig Wittgenstein, considered by many to be one of the most important philosophers of the 20th century.[4]Ludwig Wittgenstein | Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy And whether due to genetics, upbringing, or circumstances, the story above is an all-too-common story of autistic people. In this post, I explore the research literature on suicidality among autistic people.

Disclaimer

Public awareness can be an effective method of suicide prevention and support. But the following article is intended as an information resource only. If you are experiencing a life-threatening situation, call your local crisis line. In Canada, that’s the Canada Suicide Prevention Service (℡: 1 833 456 4566).

And although not support groups per se, you are also welcome in our Facebook group, the Embrace Autism Community. Many of our members have reported feeling a lot better after experiencing our autistic community.

Suicidal ideation

Let’s first look at what the research shows about suicidal thoughts, also known as suicidal ideation. Research from 2014 by Sarah Cassidy et al. shows that of the 374 autistic adults (256 men and 118 women):[5]Suicidal ideation and suicide plans or attempts in adults with Asperger’s syndrome attending a specialist diagnostic clinic: a clinical cohort study (Cassidy, 2014)

- 31% (116) self-reported depression.

- 66% (243) self-reported suicidal ideation.

- 35% (127) self-reported plans or attempts at suicide.

Those are some shocking statistics, are they not? The research shows that autistic adults are significantly more likely to report lifetime experience of suicidal ideation than the general population in the UK (17%), people with psychosis (59%), and even people with one, two, or more medical illnesses.[6]Suicidal ideation and suicide plans or attempts in adults with Asperger’s syndrome attending a specialist diagnostic clinic: a clinical cohort study (Cassidy, 2014)

One interesting thing to note here is that the number of autistic people who report having suicidal thoughts is much greater than the number of autistic people who report depression. How can that be? The answer is likely to be found in alexithymia—a condition that co-occurs in 40–65% of autistic people.[7]Brief report: cognitive processing of own emotions in individuals with autistic spectrum disorder and in their relatives (Hill et al., 2004)[8]The validity of using self-reports to assess emotion regulation abilities in adults with autism spectrum disorder (Berthoz & Hill, 2005) Two of the core aspects are difficulty identifying and describing emotions. As a result, autistic people tend to underreport depressive symptoms, and I speak from experience.

I struggled with depression for a long time, yet I did not fully realize I was depressed. During my 20s I would think about death often, and I came very close to attempting to kill myself in 2011 (described later in this article), yet I still had doubts about whether my general state of mind constituted a depression or suicidal ideation. It wasn’t until recently—years later, after seeing a significant reduction in alexithymia—that I was able to acknowledge how mentally unwell I had been.

So people with alexithymia aren’t necessarily able to report their feelings accurately. This can be important information for those who have to assess the threat level of a crisis situation; for instance, an autistic person who experiences a meltdown in public. Read our alexithymia guide below for more information on alexithymia and its consequences.

Alexithymia & autism guide

A 2014 review

A systematic review of the literature on autism and suicidality from 2014, by Magali Segers and Jennine Rawana, shows that:[9]What Do We Know About Suicidality in Autism Spectrum Disorders? A Systematic Review (Segers & Rawana, 2014)

- 10.9–50% of autistic people show suicidality.

- 7.3–15% of suicidal populations are autistic, which is an incredibly significant subgroup.

- Identified risk factors included peer victimization, behavioral problems, being black or hispanic, being male, lower socioeconomic status, and lower level of education.

A 2018 review

A systematic review from 2018 by Darren Hedley and Mirko Uljarević that included data from 2013–2018 shows that:[10]Systematic Review of Suicide in Autism Spectrum Disorder: Current Trends and Implications (Hedley & Mirko Uljarević, 2018)

- 72% of autistic people experience suicidal ideation—significantly higher than what the 2014 review indicated.

- 7–47% of autistic people have made suicide attempts.

- 0.31% of premature deaths in autistic people were due to suicide, which is significantly higher than in the general population (0.04%).[11]Premature mortality in autism spectrum disorder (Hirvikoski et al., 2016)

Suicide rates

In 2019, a 20-year long study by Anne V. Kirby et al. on suicide death in a statewide autism population found that:[12]A 20-year study of suicide death in a statewide autism population (Kirby et al., 2019)

- The risk of suicide death was found to be greater in autistic people than non-autistic people.

- The risk of suicide death in autistic people increased over time between 2013–2017 (but did not significantly differ between 1998–2012).

- In 2013–2017, the incidence of suicide for the autistic population was 0.17%, compared to 0.11% for the non-autistic population. The difference may seem trivial, but this is a suicide rate that is almost 55% greater than the general public!

- Autistic females were over 3 times as likely to die from suicide as non-autistic females.

- Young autistic people were at over 2 times the risk of suicide than non-autistic young people.

- But autistic people were less likely than others to die from firearm-related suicides.

The fact that autistic people tend to go for non-firearm suicide methods should be considered when developing suicide prevention efforts or dealing with crisis situations.

Sex differences

Research from 2019 by Katsunaka Mikami et al. looked at 94 people, aged less than 20 years, who had attempted suicide and had been hospitalized in an emergency department. Their research shows that:[13]Gender Differences in the Suicide Attempts of Adolescents in Emergency Departments: Focusing on Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder (Mikami et al., 2019)

- The mean age of males was 17.1, and 16.9 for females.

- Autistic people who attempted to end their lives were significantly more frequently male.

- The attempt methods were more serious in males, and their length of stay in the emergency room was longer.

- Yet the rate of outpatient treatment was lower in males.

- Adjustment disorder was significantly associated with suicide attempts in autism (compared to mood disorders in non-autistics).[14]Clinical features of suicide attempts in adults with autism spectrum disorders (Kato et al., 2013)

The research also shows that males were less likely to visit psychiatric service prior to attempting suicides, and may be more likely to complete suicides. Since autistic suicide attempters are more likely to be male with adjustment disorder, the researchers note:[15]Gender Differences in the Suicide Attempts of Adolescents in Emergency Departments: Focusing on Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder (Mikami et al., 2019)

ED visits offer a window of opportunity to provide suicide prevention interventions for adolescents, and therefore, psychiatrists in EDs have a crucial role as gatekeepers of preventing suicide reattempts, especially in adolescent males including individuals with ASD having adjustment disorder.

Suicide rates per country

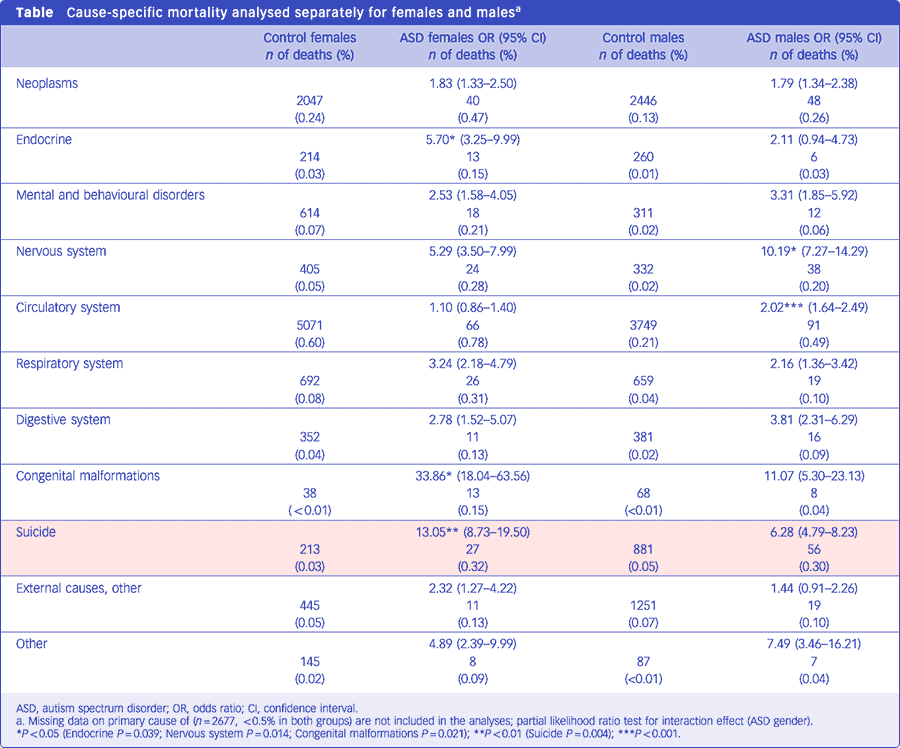

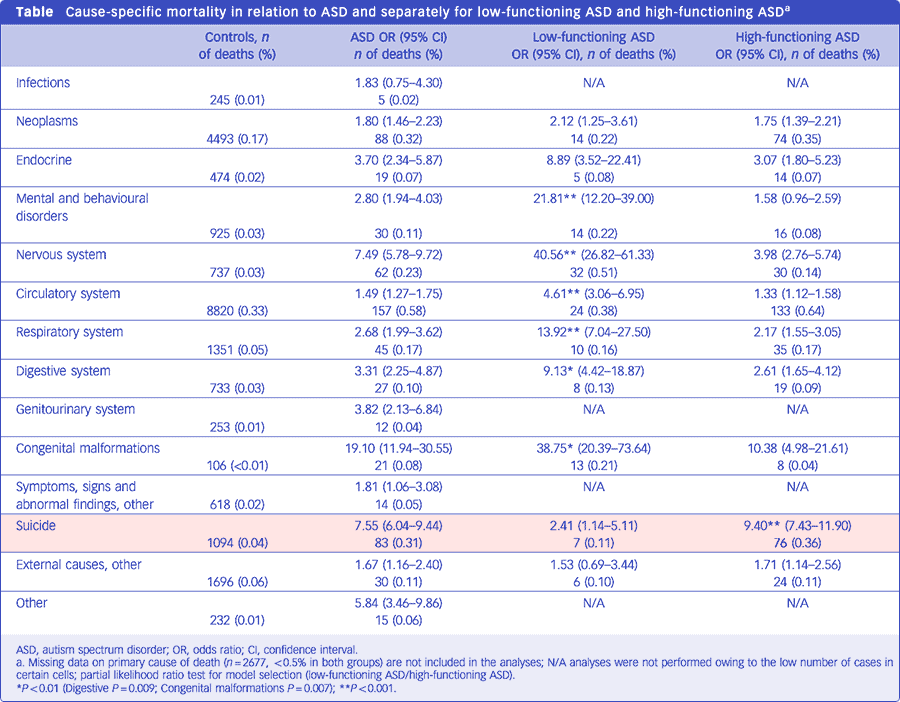

I wasn’t able to get statistics on suicide rates of autistic people per country, and research on national figures seem to be practically non-existent as well. But I did find one large study from Sweden on mortality rates in autism, based on a sample of 27,122 diagnosed autistic people. The study showed that during the observed period:[16]Premature mortality in autism spectrum disorder (Hirvikoski et al., 2016)

- 2.60% (706) of autistic people died, compared to 0.91% (24,358) in the general population.

Of those premature deaths:[17]Premature mortality in autism spectrum disorder (Hirvikoski et al., 2016)

- 0.32% (27) of autistic women died by suicide, compared to 0.03% (213) of non-autistic women.

- 0.30% (56) of autistic men died by suicide, compared to 0.05% (881) of non-autistic men.

- So autistic women are 0.02% more likely to die by suicide than autistic men; whereas among non-autistics, men are 0.02% more likely to die by suicide than women.

The researchers also accounted for intellectual disability, and found the following:[18]Premature mortality in autism spectrum disorder (Hirvikoski et al., 2016)

- 0.11% (7) of autistic people with intellectual disability (classified low-functioning by the paper) died by suicide.

- 0.36% (76) of autistic people without intellectual disability (classified high-functioning by the paper) died by suicide.

So based on this study, autistic people without an intellectual disability are more than three times as likely to die by suicide than those with an intellectual disability. And note that if you exclude autistic people with an intellectual disability, the average suicide rate for autism jumps from 0.31% to 0.36%. I don’t know if these numbers can be generalized beyond Sweden, but it’s interesting that the average suicide rate they found is the same as reported by the systematic review mentioned earlier.

Suicide methods

This topic may be very sinister, and you are welcome to skip it. However, for people who deal with crises, the information below could be valuable.

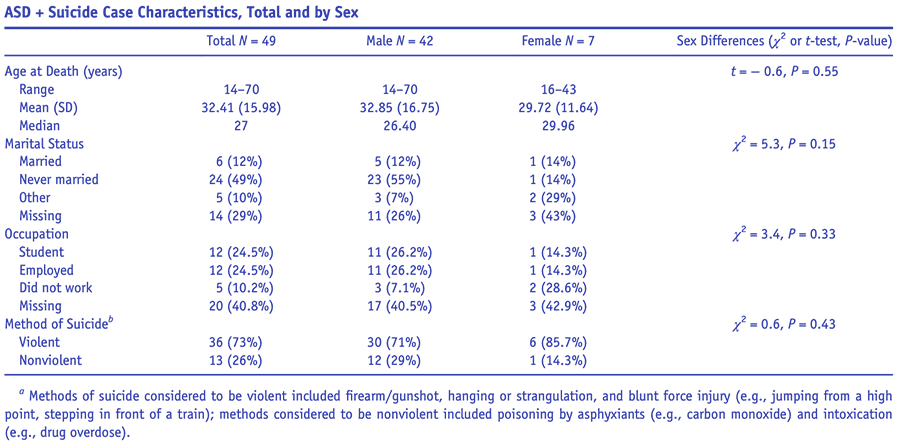

In the diagram above, you can see that 71% of autistic men killed themselves by violent means, compared to 85.7% of autistic women. Methods of suicide considered to be violent included firearm/gunshot, hanging or strangulation, and blunt force injury (e.g., jumping from a high point, stepping in front of a train); and methods considered to be nonviolent included poisoning by asphyxiants (e.g., carbon monoxide) and intoxication (e.g., drug overdose). The fact that more autistic women killed themselves by violent means is significant, because it’s in stark contrast with findings on non-autistic women and suicide; most prevalent methods of suicide attempts were pharmacological drugs abuse (42.31%) and exsanguination (25.64%), and the least frequent were poisoning and throwing oneself under a moving car (1.28%).[19]Gender differentiation in methods of suicide attempts (Tsirigotis et al., 2011)

So what explains the difference? Why do autistic women tend to die by suicide in more violent ways than autistic men, and especially compared to non-autistic women? Well, let me first briefly explain something else. Suicide is—at least in part—a learned response to stress.[20]Suicide as a learned behavior (Lester, 1987) What this means is that people learn about suicide and suicide methods through exposure to news stories, the Internet, books, movies, and other channels of communication,[21]Media and Suicide: International Perspectives on Research, Theory, and Policy (Stack & Bowman, 2017) and will often use those methods (and even locations) they have learned about and have access to. This is called coupling behavior, sometimes described in the literature as the availability hypothesis. One example of coupling behavior is the high frequency of railway suicides in the Netherlands,[22]Train suicide mortality and availability of trains: A tale of two countries (van Houwelingen et al., 2013) which is due to the accessibility of trains, as well as frequent reports of railway suicides—both on the radio as well as on the trains that are involved in incidents. For more information on coupling behavior, read the book Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell, or read an excerpt from the book below.

Coupling Theory

When it comes to suicide methods in the general population, it’s thought that the cinema plays a role in the gendering of suicide methods through social learning[23]Suicide and the Creative Arts (Lester & Stack, 2009)[24]Media and Suicide: International Perspectives on Research, Theory, and Policy (Stack & Bowman, 2017) (coupling). And while this is admittedly extremely speculative, I think how autistic people relate to movies, series, books, etc. could be a significant cultural factor that drives some of the sex differences. It’s thought that because autistic women experience more pressure to perform socially[25]Autism—It’s Different in Girls | Scientific American and to mask their autistic proclivities,[26]“Putting on My Best Normal”: Social Camouflaging in Adults with Autism Spectrum Conditions (Hull et al., 2017)[27]Linguistic camouflage in girls with autism spectrum disorder (Parish-Morris et al., 2017)[28]Understanding and recognising the female phenotype of autism spectrum disorder and the “camouflage” hypothesis: a systematic PRISMA review (Allely, 2019)[29]The Female Autism Phenotype and Camouflaging: a Narrative Review (Hull, Petrides & Mandy, 2020) they tend to focus more on using movies and books to learn and internalize social scripts, so they become better adept at interpersonal relations. I think this greater tendency to engage in social learning also increases the possibility of internalizing certain suicide methods. For more information about how autistic women in particular internalize social scripts, have a look at the following post:

Autism & movie talk

Whether through movies and literature or other means, research shows that cultural factors are driving the variation in suicide deaths by sex in the general population.[30]Annual Research Review: A meta-analytic review of worldwide suicide rates in adolescents (Glenn et al., 2019) So it’s likely that there are also subcultural factors in the autism community that drive some of these differences.

Causes

When it comes to the causes of suicidal ideation and suicidal behaviors, I think it makes sense to first look at the research literature to see what factors play a role. After that, I will highlight the significance of a few of these factors by offering my personal experience, which I think is shared by many autistic people, but isn’t fully expressed by the research papers I looked at.

Loneliness

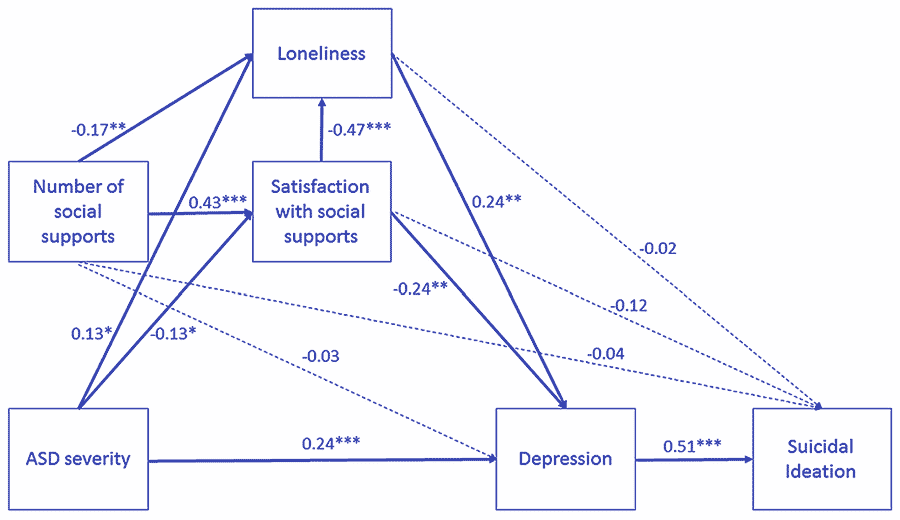

Research from 2018 by Darren Hedley et al. indicates that:[31]Risk and protective factors underlying depression and suicidal ideation in Autism Spectrum Disorder (Hedley et al., 2018)

- Loneliness is the main risk factor for depression and suicidal ideation.

- Social support is a protective factor for depression and suicidal ideation.

In the diagram below you can see the correlations between autistic traits, loneliness, the number of social supports, satisfaction with the available social support, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation for autistic individuals.

Note also that alexithymia contributes to loneliness and social isolation.[32]Alexithymia – not autism – is associated with frequency of social interactions in adults (Lerner et al., 2019) And in autistic people, loneliness also acts on thoughts of self-harm indirectly through depression.[33]Understanding depression and thoughts of self-harm in autism: A potential mechanism involving loneliness (Hedley et al., 2017)

Anxiety

Research from 2019 by Deanna Dow et al. found that a substantial proportion of autistic people reported a lifetime history of:[34]Anxiety, Depression, and the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide in a Community Sample of Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder (Dow et al., 2019)

- Anxiety (63%)

- Depression (55%)

- Suicide attempts (19%)

- Recent suicidal ideation (12%)

Note how significant anxiety is. And what can come as a real surprise to people is that for autistic people to show suicidal thoughts or behaviors, they don’t necessarily need to be depressed. Sometimes, overwhelm due to pressures in life and having to face too many obstacles can lead to coping mechanisms some might consider sinister. For example, quite a few autistic people report morbid fantasies such as of dying in their sleep as a way to rest and escape responsibilities in life. So there may not even be an explicit wish to die, but a profound desire to not have to deal with our stress anymore.

Distress

So our response to distress can lead to suicidal thoughts and behaviors. In a paper from 2013, Eric Alan Storch et al. suggest the following characteristics may increase the risk of becoming stuck in distressing and potentially overwhelming depressive thought patterns, without having the perspective to understand that these states are temporary or time-limited:[35]The Phenomenology and Clinical Correlates of Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors in Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorders (Storch et al., 2013)

- Rigidity.[36]Sensory clusters of toddlers with autism spectrum disorders: differences in affective symptoms (Ben-Sasson, 2008)

- Limited cognitive flexibility.[37]Parent, teacher, and self perceptions of psychosocial functioning in intellectually gifted children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder (Foley Nicpon, 2010)

- Challenges in understanding the temporal sequencing and durability of events.[38]Psychopathology in children and adolescents with autism compared to young people with intellectual disability (Brereton, Tonge & Einfeld, 2006)[39]Anxiety in high-functioning children with autism (Gilliot & Walter, 2001)

That last one particularly resonates with me. When I’m in emotional distress, it feels timeless; like the distress will never stop. As irrational as it is, when our suffering seems indefinite, even a permanent measure can seem like an attractive way to deal with it.

Camouflaging

In 2018, Sarah Cassidy et al. looked into the risk markers for suicidality in autistic adults and found that:[40]Risk markers for suicidality in autistic adults (Cassidy et al., 2018)

- 72% of autistic adults scored above the recommended psychiatric cut-off for suicide risk on the Suicide Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised (SBQ-R), compared to 33% in the general population.

- Controlling for a range of demographics and diagnoses, an autism diagnosis and self-reported autistic traits in the general population significantly predicted suicidality.

They also found that in autistic adults, the following factors significantly predicted suicidality:[41]Risk markers for suicidality in autistic adults (Cassidy et al., 2018)

- Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) — This seems to be a destructive form of stimming, meaning a coping mechanism to deal with stress and regulate one’s emotions.[42]Camouflaging of repetitive movements in autistic female and transgender adults (Wiskerke, Stern & Igelström, 2018)

- Camouflaging — The more one has to camouflage their (autistic) proclivities, the less one can show up authentically and be recognized and appreciated for who they are. Considering we are social animals, this can cause a great deal of suffering.

- Number of unmet support needs — Of course, the discrepancy between support needs and the lack of actual support can cause a lot of suffering.

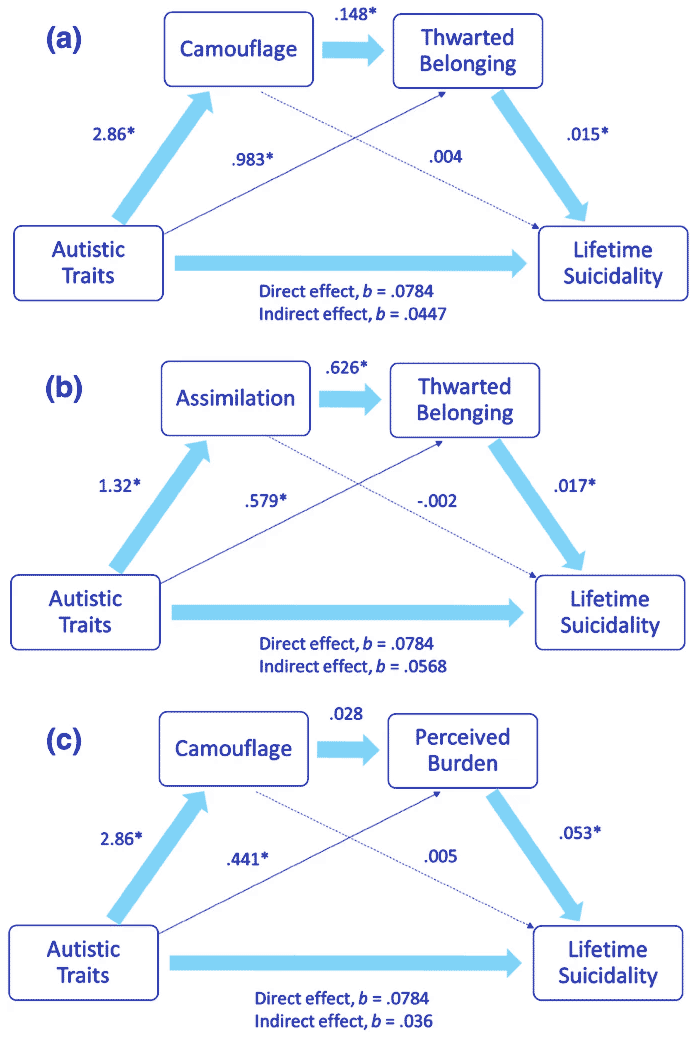

Research by Sarah Cassidy et al. from 2020 again found camouflaging to be a relevant factor, and further found that the following variables were significantly correlated with suicidal thoughts and behaviors:[43]Is Camouflaging Autistic Traits Associated with Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviours? Expanding the Interpersonal Psychological Theory of Suicide in an Undergraduate Student Sample (Cassidy et al., 2020)

- Autistic traits

- Camouflaging (specifically Assimilation)

- Depression

- Anxiety

- Thwarted belongingness

- Perceived burdensomeness

For more information on autism and camouflaging, have a look at the following post:

Autism & camouflaging

Social exclusion

Camouflaging has a negative impact on our mental health and sense of belonging. But we nevertheless tend to feel the need to, because not doing so can result in social exclusion, rejection, or worse.

So it’s important to emphasize that suicidal ideation isn’t intrinsic to autism. The overwhelming majority of mental health issues of many marginalized groups come from exclusion and aggressive discrimination.[44]Multifactorial discrimination as a fundamental cause of mental health inequities (Khan, Ilcisin & Saxton, 2017). Rejection, nonaffirmation, and victimization leads to suicidal ideation, depression, increased perceived burdensomeness, etc.[45]Suicidal ideation in transgender people: Gender minority stress and interpersonal theory factors (Testa et al., 2017) This applies to autism, sexuality, skin color, being poor, etc.[46]LGBT Identity, Untreated Depression, and Unmet Need for Mental Health Services by Sexual Minority Women and Trans-Identified People (Steele et al., 2017) Minority stress is also significantly associated with high levels of distress[47]Minority Stress and Mental Health in Gay Men (Meyer, 1995) and physical health problems.[48]The relationship between minority stress and biological outcomes: A systematic review (Flentje et al., 2019)

My experience

I want to briefly explain the two times I came close to taking my own life, because I think it offers some insight into the autistic mind that isn’t necessarily reported and captured by the research. For one, I think it doesn’t necessarily take general depression or loneliness. I think many suicides among autistic people likely occur as an impulse decision to—permanently—deal with temporary overwhelm. We can experience a meltdown due to a drastic change in our lives, or feel like life is too hard to cope with. We may not have a specific wish to die, but are sometimes just looking for some relief. For a long time, I would often fantasize of dying in my sleep. I think just thinking about it gave me a sense of relief. I think subconsciously I was telling myself, “Just make it through today. Tonight you can rest, and you may never have to struggle again”.

Given their difficulties in mentalizing emotionally charged situations, what is usually considered a stressful life situation may come to ASD patients as a true traumatic event, while suicide may represent the only extreme way to express inner feelings and to cope with conflicts.[49]Suicide and autism spectrum disorder: The role of trauma (Dell’Osso, Gesi & Carmassi, 2016)

The first time

- Age: 19

- Method: Train

- Cause: Significant change

The first time I came fairly close. I had visited my parents for the weekend, like I would do most weekends back then. On the day I was going to take the train back home, my girlfriend broke up with me. At the train station, I felt really desperate and scared, and considered jumping in front of the train to make it stop. Since I would often take the train, I had quite a few experiences of train delays due to people jumping in front of trains—especially near Christmas—so you can see where I picked up the idea. I think you can also see where they picked it up. Once an idea like this spreads around—the idea to end your life in a particular way that seems convenient, at a particular location that is accessible—it can spread like a virus. This is the coupling I talked about earlier. It doesn’t have an immediate influence on society; most people don’t experience suicidal thoughts. But the knowledge will stick in the back of your mind. And when you are desperate enough, you may just—almost on impulse—decide to jump…

Anyway, I obviously didn’t do that. I don’t recall if it was a train driver or a police officer, but he saw me crying hysterically and asked me what was going on. I explained to him that my girlfriend broke up to me. I don’t recall what he said, but he was very understanding, which felt validating. I think that calmed me down enough to keep going. He assessed whether I was (still) a threat to myself, and went on his merry way.

The second time

- Age: 23

- Method: Train

- Cause: General overwhelm

The second and last time I came close to ending it all was back in 2011. I wasn’t doing well at this time of my life. I was under a great deal of pressure from various sources, and honestly became a bit psychotic—though I didn’t know it at the time. I might explain more about that in a future post, but it’s not that relevant to the story. I didn’t visit my parents as frequently anymore at this point, but I did that weekend. I was in the train, on my way home, when my phone stopped working. I didn’t have the money for a new phone, and I panicked. That would be a fairly intense reaction for me now, but at the time, I felt generally desperate, and my phone is something I greatly relied on. For starters, it was my only alarm clock! How do I wake up in time for school now?

I arrived at the station where I had to switch trains. The next train was going to arrive in 15 minutes. I don’t exactly remember what went through my head, but I know that my phone breaking was the final drop. It would have been a very silly reason to die over—especially in light of the fact that my phone wasn’t even broken, as I found out later—but I was just perpetually overwhelmed in life and I couldn’t handle any other setbacks.

I was standing near the edge of the platform. The sky was pitch black. It felt like a dream. The next train came in, and I was ready to jump. Again, I obviously didn’t. But I actually shocked myself with how close I came to going through with it. And over something so trivial. Instead of jumping, I took the train back to Rotterdam, but instead of going home, I first went to my friend’s home. It was midnight, and we had school the next day. But he invited me in, and as I told him what was going on, I broke down crying. I stayed for a while, and then went home.

Family

Lastly, I want to briefly go into whether autistic people tell their friends and family. I obviously told my friend what happened, but I wouldn’t ordinarily talk about my feelings. Feelings either brought me pain or got me in trouble, so I numbed them out over the years, and spending time with friends meant doing things that distract you from your personal feelings.

When it comes to family, I think it wasn’t until years later that I told my parents about what happened. Again, I didn’t tell them much about my feelings, but they did know I was struggling. I didn’t want them to worry about me. They mean well by worrying, but it can become an annoyance or even painful to deal with. Annoying in the sense that it becomes another obstacle to deal with, and one way to deal with it is to play down the seriousness of the situation, camouflage, and basically take care of other people’s feelings. Because while people’s concern can be validating and constructive, there are also many people who don’t know how to respond, become emotional themselves, and inadvertently end up making it about them. For an autistic person—especially one who is dealing with trauma—it can be an overwhelming prospect to start considering all these potential scenarios. It’s often a lot easier not to say anything.

I asked in the Embrace Autism Community whether those who experienced suicidal ideation would tell their family and friends about it, and I received pretty consistent results; most gave similar responses about them not wanting their parents and friends to worry.

Besides not wanting others to worry and not wanting or able to deal with their reactions to telling them, I want to repeat what I alluded to earlier in the article. In my 20s my alexithymia was high, which meant I probably wouldn’t have been able to relay to family and friends how desperate I felt at times. I knew I was struggling, and yet I was still prevented from understanding my own emotions in any deep way, and recognize how bad I was truly doing. Part of it was probably also necessary self-denial; I survived by not fully acknowledging my emotional experiences, which I wouldn’t have been able to handle or appreciate at the time. This might be at the core of what alexithymia is; a defense or protection against highly emotional events.[50]Towards a classification of alexithymia: primary, secondary and organic (Messina et al., 2014) As you can imagine, the more sensitive a person is to events in the world—and autistic people tend to be exactly that—the greater the incentive to cut off our experience from those sensitivities, if they don’t work in our favor.

Or, if things truly become too much, to cut short our very life to make the hardship stop.

At the start of this post, I told you how Ludwig Wittgenstein’s doctor told him he might live only a few days, and he reportedly replied, “Good!” I don’t know if he felt a sense of relief or was expressing a dark sense of humor, but just before losing consciousness for the last time the next day, he said:

Tell them I’ve had a wonderful life.

In an upcoming post, we will look at interventions and ways

to help autistic people who experience suicidal thoughts.

Comments

Let us know what you think!