Alexithymia is very common among autistic people; research indicates that at least 49.93%[1]Investigating alexithymia in autism: A systematic review and meta-analysis (Kinnaird, Stewart, & Tchanturia, 2019) of us have alexithymia—or even as high as 85% with slight to severe alexithymia[2]Measuring the effects of alexithymia on perception of emotional vocalizations in autistic spectrum disorder and typical development (Heaton, 2012)—compared to 4.89–13% in the general population.[3]Prevalence of alexithymia and its association with sociodemographic variables in the general population of Finland (Salminen et al., 1999)[4]Age is strongly associated with alexithymia in the general population (Matilla et al., 2006)[5]Investigating alexithymia in autism: A systematic review and meta-analysis (Kinnaird, Stewart & Tchanturia, 2019)

It’s so common that some symptoms generally attributed to autism (to the point of being part of the diagnostic criteria for autism) actually stem from alexithymia instead! More about that later in this post.

So what is alexithymia, and how does it develop?

Alexithymia

Alexithymia is a condition where you have challenges identifying and describing emotions in the self. Essentially, alexithymia is a difference in emotional processing. The term was introduced by Peter Emanuel Sifneos in 1972, from the Greek a for lack, lexis for word, and thymos for emotion, meaning lack of words for emotions or simply no words for emotions.[6]Peter Emanuel Sifneos | The Harvard Gazette (2010)

More comprehensively though, alexithymia is defined by:

- Difficulty identifying feelings.

- Difficulty distinguishing between feelings and the bodily sensations (interoception) of emotional arousal.

- Difficulty describing feelings to other people.

- Difficulty identifying facial expressions.

- Difficulty identifying/remembering faces. (an extreme form of the latter is prosopagnosia/face blindness)

- Difficulty fantasizing.

- A thinking style focused on external events (often avoiding inner experiences).

You don’t need to experience all or most of these to qualify for alexithymia, however. I will explain later in this post which of the 7 points above we tend to see in autistic people.

When it comes to difficulty identifying and describing feelings, experiences probably vary, but mine goes like this. When I am asked about an emotional experience or what I think another person’s emotional experience is like, my initial response tends to be “I don’t know”. But Natalie has learned to not accept this for an answer. After she asks me a second time, I can usually access my emotions better. So the identification of feelings often comes with a delay when pressed.

When I got diagnosed with autism at 25, my diagnostician said I “have a lack of internal dynamics”. It took me quite a while to figure out what he meant, but I now think what he was alluding to was alexithymia. I used to express my emotions with vague approximations (I feel good, or I feel content, or I feel bad) if at all; and I still do to a degree, but I have gotten a lot better at exploring my inner emotional world and giving it a more nuanced expression when someone asks me about my feelings. Learning about alexithymia has been profoundly useful for me. I hope it is as illuminating for you as well.

For more information on the experience of alexithymia, I highly recommend reading

the post below, which I wrote when my alexithymia was particularly high:

The experience of alexithymia

Types of alexithymia

Alexithymia can be divided into two types:

- Cognitive alexithymia — The cognitive dimension of alexithymia has to do with difficulties in identifying, verbalizing, and analyzing emotions. Basically, this is #1–4 from the list above.

- Affective alexithymia — The affective dimension of alexithymia has to do with differences in imagination and emotional arousal (heightened emotional activity as a result of a stimulus). This refers to #6 and #7 from the list above.

There are also a few more types of alexithymia based on etiology (meaning different causes), which I will discuss below.

Causes

Alexithymia can develop in three different ways:

Primary alexithymia

- Cause: genetics & family relations

- Description: Primary alexithymia is a lifelong condition, caused by childhood trauma[7]Alexithymia and psychotherapy (Krystal, 1979) or negative primary caregivers interactions.[8]Adult attachment, alexithymia, symptom reporting, and health-related coping (Wearden et al., 2003) So primary alexithymia develops early, and becomes molded during childhood and early adult years as personality traits.[9]Towards a classification of alexithymia: primary, secondary and organic (Messina et al., 2014) Hence primary alexithymia is also called trait alexithymia.

Secondary alexithymia

- Cause: psychological distress

- Description: Secondary alexithymia refers to alexithymic characteristics resulting from psychological stress, chronic disease, or organic processes (such as brain trauma or a stroke) that occur after childhood.[10]Towards a classification of alexithymia: primary, secondary and organic (Messina et al., 2014) Secondary alexithymia is less ingrained, as it’s based on (temporary) states rather than personality traits. As such, it’s also referred to as state alexithymia.

Organic alexithymia

- Cause: trauma (vascular or other brain damage)

- Description: A sub-category of secondary alexithymia, organic alexithymia is caused by damage to brain structures involved in emotional processing.[11]Towards a classification of alexithymia: primary, secondary and organic (Messina et al., 2014)

Defense mechanism

In our initial post on alexithymia (entitled Alexithymia), I argued how alexithymia is likely a protection mechanism—not just a nuisance. I argued that in an environment where your emotions just get you into trouble or makes things too hard to bear, alexithymia can increase and consequence reduce your emotional experience so you are less burdened by your emotions. As it turns out, I was correct!

Research shows that alexithymia is a defense or protection against highly emotional events.[12]Towards a classification of alexithymia: primary, secondary and organic (Messina et al., 2014) This view is also supported by the higher levels of alexithymia found in holocaust survivors[13]Alexithymia in Holocaust survivors with and without PTSD (Yehuda et al., 1997) and sexual assault victims.[14]Alexithymia in victims of sexual assault: an effect of repeated traumatization? (Zeitlin et al., 1993)

Research from 2012 by Oriel FeldmanHall, Tim Dalgleish, and Dean Mobbs also shows that people who are high on the alexithymia spectrum report less distress at seeing others in pain.[15]Alexithymia decreases altruism in real social decisions (FeldmannHall, Dalgleish & Mobbs, 2012) That may sound good for the alexithymic individual (although personal distress in alexithymics is high[16]Correlation between theory of mind and empathy among alexithymia college students (Xue, Hongchen & Lei, 2017)), but as a consequence, they also behave less altruistically.[17]Alexithymia decreases altruism in real social decisions (FeldmannHall, Dalgleish & Mobbs, 2012)

I can personally attest to that. For example, when I was 27 or so, as I was walking to the grocery store, a few meters away from me a woman in her early 30s fell off her bike. I chuckled as I continued walking, and to my surprise, a man and a woman (who had no connection with each other as far as I saw) came running to help her get back on her bike. I thought it was all a bit dramatic, like you might see in the movies. I thought to myself, “If it was a guy falling you would likely not have come to the rescue.” The reason I could laugh about what happened was that I saw she was fine anyway. Had it been serious, I would have helped out if no one else did. But I also figured I had a lesser inclination to help because I fell off my bike many times. Yes, it hurts. And then I get up. People “helping me out” have always embarrassed me; it was much better if everyone just pretended they hadn’t seen anything.

That was the old alexithymic me. Today I am a new alexithymic me. While I think I would likely respond the same way to that situation as I did then if it were to happen today, I also recognize that not helping out because I didn’t want to be helped when I fell off my bike, is a projection; how I want others to respond to me is not necessarily how others want people to respond. Being autistic and alexithymic, I’m not necessarily in tune with how people want me to respond.

Let’s look at how alexithymia presents itself in autism specifically. It’s actually really fascinating!

Alexithymia in autism

Although I have not been able to substantiate this with research, I believe autistic people tend to have primary alexithymia, though secondary alexithymia could also occur in autistic people.[18]Response to “Features of Alexithymia or features of Asperger’s syndrome?” by M. Corcos in European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 12, 2003 (Fitzgerald, 2004) Organic alexithymia likely has the same occurrence in both autistics and non-autistics. As it happens, when I was 13 I was catapulted out of a tree (long story) and cracked my skull. Although my experience is different, according to my mother I changed personality since then, so I might have organic alexithymia on top of primary alexithymia. Over the years I managed to reduce it considerably, however.

In any case, research from 2005 by Sylvie Berthoz and Elisabeth Hill shows that autistic people have cognitive alexithymia specifically.[19]The validity of using self-reports to assess emotion regulation abilities in adults with autism spectrum disorder (Berthoz & Hill, 2005) So that means challenges with identifying and describing feelings, challenges with distinguishing between feelings and bodily sensations (called interoception), difficulties with identifying facial expressions, and difficulties with identifying and remembering faces.

So, issues with theory of mind often attributed to autism? Research shows that’s alexithymia[20]Impaired self-awareness and theory of mind: An fMRI study of mentalizing in alexithymia (Moriguchi et al., 2006)[21]Correlation between theory of mind and empathy among alexithymia college students (Xue, Hongchen & Lei, 2017) (although research by Bethany Oakley, Rebecca Brewer, Geoff Bird and Caroline Catmur shows it’s not challenges with theory of mind but with emotion recognition that relates to alexithymia[22]No Evidence for an Opposite Pattern of Cognitive Performance in Autistic Individuals with and without Alexithymia: a response to Rødgaard et al.) Do you tend to forget people’s faces? That’s alexithymia. Do you not recognize that you are hungry until hours later, at which point your sugar levels have dropped and you feel sick? Yep, that’s alexithymia. Specifically, that’s diminished interoception due to alexithymia. So we may be less aware of our breathing, hunger, thirst, or our heart rate.

Interestingly, research by Punit Shah, Caroline Catmur & Geoff Bird from 2016 shows that emotional and interoceptive signals don’t influence the decision-making process in autistic people with alexithymia, unlike in neurotypical people with alexithymia.[23]Emotional decision-making in autism spectrum disorder: the roles of interoception and alexithymia (Shah, Catmur & Bird, 2016) But essentially, it seems all emotion processing differences thought to be part of autism are actually due to alexithymia![24]The Multifaceted Nature of Alexithymia – A Neuroscientific Perspective (Goerlich, 2018) In a paper from 2013, Geoff Bird and Richard Cook refer to this as the alexithymia hypothesis.[25]Mixed emotions: the contribution of alexithymia to the emotional symptoms of autism (Bird & Cook, 2013)

What we don’t tend to experience is affective alexithymia; so we do not generally have a limited imagination or a lack of fantasies. I think our imagination is often quite rich (as a kid I was always described as a dreamer, and would write imaginative stories), and a lot of us have creative abilities and interests. However, I have heard some accounts of autistic people who only dream about practical and mundane things, which suggests that some autistic people have affective alexithymia as well.

So now let’s talk about the aspects we thought were part of autism, but are actually due to alexithymia.

Social isolation

The first aspect we perhaps mistakenly thought was part of autism for the longest time is low sociability. Research from 2019 by Matthew D. Lerner et al. shows that:[26]Alexithymia – not autism – is associated with frequency of social interactions in adults (Lerner et al., 2019)

- Autistic adults had a similar amount and pattern of social interactions with others, compared to non-autistic adults.

- Difficulties with identifying emotions in both the self and others were associated with fewer social interactions.

- The severity of alexithymia symptoms predicts fewer social interactions regardless of autism status.

This seems to suggest that when you have a lower awareness of emotions in the self and others, you are less likely to be socially motivated, or maybe more likely to be put off by the social challenges. I can imagine that if you don’t have good awareness or a significant understanding of the emotions of yourself and others, you will not be interested in emotions and interacting, and are more likely focused on activities and exploring concepts. That is certainly true for me. I am a lot more object-oriented than people-oriented. Talking a lot about feelings and relations bore me, unless there are interesting psychological or philosophical layers to be explored.

Research from 2010 by Jamileh Zareia and Mohammad ali Besharatb also shows a range of interpersonal problems related to alexithymia, including:[27]Alexithymia and interpersonal problems (Zarei & Besharat, 2010)

- Assertiveness

- Sociability

- Submissiveness

- Intimacy

- Responsibility

- Controlling

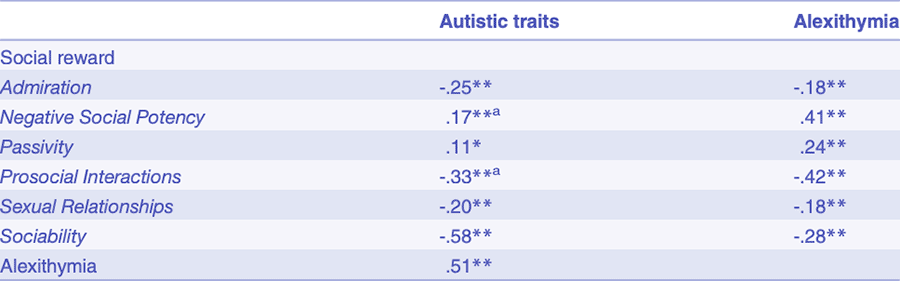

Research from 2015 by Lucy Foulkes et al. also showed that:[28]Common and Distinct Impacts of Autistic Traits and Alexithymia on Social Reward (Foulkes et al., 2005)

- Both autistic traits and alexithymia reduce admiration (the enjoyment of being flattered).

- Both autistic traits and alexithymia increase negative social potency (the enjoyment of being cruel, callous and using others for personal gains), but more so due to alexithymia.

- Both autistic traits and alexithymia increase passivity (the enjoyment of giving others control and allowing them to make decisions).

- Both autistic traits and alexithymia decrease prosocial interaction (the enjoyment of having kind, reciprocal relationships), but alexithymia more so.

- Both autistic traits and alexithymia decrease sexual relationships (the enjoyment of having frequent sexual experiences), but autism more so.

- Both autistic traits and alexithymia decrease sociability (the enjoyment of engaging in group interactions), but autism much more so.

In the table below, you can see an overview of the associations of different factors of social reward with autistic traits and alexithymia.

So if you isolate yourself a lot, or experience other interpersonal challenges, it may be due to your (co-occurring) alexithymia rather than your autism specifically, although both factors seem to influence social reward in different ways.

Lower empathy

According to the simulation theory of empathy, people simulate the feelings they observe in others in their mind, so that they can better understand and predict the feelings of others. So having challenges with interpreting and describing your own emotions and internal processes will result in difficulties empathizing with others’ feelings.

So that myth about autistic people not showing empathy? Well, it IS a myth, but for different reasons than you might think; autistic people indeed sometimes fail to respond empathetically, but it’s not due to their autism, but because of their alexithymia! The higher the alexithymia, the more potential problems with empathy.

And it’s not just cognitive empathy that is diminished by alexithymia! Research from 2018 by Cari-lène Mul et al. shows that autistic people with alexithymia have both lower cognitive and emotional empathy than autistic people without alexithymia.[29]The Feeling of Me Feeling for You: Interoception, Alexithymia and Empathy in Autism (Mul et al., 2018) The research also showed that autistic people have a reduced interoceptive sensitivity (they don’t feel internal bodily sensations such as hunger as readily) which was not influenced by alexithymia, and a reduced interoceptive awareness (meaning we are less aware of the bodily signals we already feel less), which was found to be influenced by both alexithymia and empathy.

Research also shows that decreased empathy causes a sense of loneliness, so that’s another reason why it’s in your best interest to focus on resolving your alexithymia.[30]Trait empathy as a predictor of individual differences in perceived loneliness (Beadle et al., 2012)

It’s important to note though that autism itself is not related to low emotional empathy. Quite the opposite, in fact. Research from 2017 by Adam Smith shows our emotional empathy is intact and even elevated[31]The Empathy Imbalance Hypothesis of Autism: A Theoretical Approach to Cognitive and Emotional Empathy in Autistic Development (Smith, 2017) (which some call empathetic overarousal,[32]The Empathy Imbalance Hypothesis of Autism: A Theoretical Approach to Cognitive and Emotional Empathy in Autistic Development (Smith, 2017) though I don’t think this is really going to catch on with the ladies). No, it’s our cognitive empathy that tends to be lower than average.[33]Impairments in cognitive empathy and alexithymia occur independently of executive functioning in college students with autism (Ziermans & de Bruijn et al., 2018)

And this is a problem for us, because research from 2018 by Jason Bos and Mark A. Stokes showed that for autistic people only, cognitive empathy is required for emotional empathy to lead to personal wellbeing.[34]Cognitive empathy moderates the relationship between affective empathy and wellbeing in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder (Bos & Stokes, 2018) What does that mean? Well, what Natalie sees in her practice is that when it comes to autistic people and trauma, they tend to be the easiest patients to help, because basically you just have to explain things to them, and just by understanding it now they tend to get better. So first cognitive empathy needs to be present, so you understand the emotions of yourself and others. It’s that understanding you need to make sense of your own emotional experiences. If you can’t make sense of them, it is difficult to find happiness in that. But also, with high alexithymia and low cognitive empathy, a lot of emotions and feelings will fly under the radar of your own awareness, while still having an effect on your mood and behaviors.

So only when cognitive empathy is high are autistic people able to experience the positive relationship between affective empathy and personal wellbeing. When cognitive empathy is low, that relationship becomes negative, meaning when more feelings come up that you are unable to process and may not even be fully aware of, your wellbeing will go down.

For more information on empathy and autism, have a look at:

Autism & empathy

Face-perception differences

It is often stated that autistic people have difficulty identifying facial expressions, but research from 2013 by Richard Cook et al. shows that the face-perception differences which we thought were due to autism are actually the cause of alexithymia.[35]Alexithymia, Not Autism, Predicts Poor Recognition of Emotional Facial Expressions (Cook et al., 2013) The research study consisted of two experiments:

Experiment 1 showed that alexithymia correlates strongly with the precision of expression attributions, whereas autism severity was unrelated to expression-recognition ability.

In other words, alexithymia lowered the precision with which both the autistic group and the control group could identify facial expressions.

Experiment 2 confirmed that alexithymia is not associated with impaired ability to detect expression variation; instead, results suggested that alexithymia is associated with difficulties interpreting intact sensory descriptions.

Experiment 2 was a matching task, where either the features of different people were merged to show 20% of another photo, or different facial expressions. The experiment showed that people with alexithymia (regardless of whether they are autistic or not) had no problems with detecting these physical differences, but nevertheless had difficulty identifying facial expressions correctly. So it’s not that we see no physical differences, but we don’t necessarily know what those differences mean. My experience is that facial expressions are sometimes quite ambiguous to me, so rather than not knowing what different facial expressions mean, my challenge is that sometimes I can imagine different emotional motivations for making that particular facial expression. I don’t believe I have a lot of difficulties identifying or describing facial expressions in general though, even though my alexithymia is high.

In any case, the researchers of the study suggest that current diagnostic criteria of autism may need to be revised, because some of the diagnostic criteria for autism actually refer to alexithymia instead.[36]Alexithymia, Not Autism, Predicts Poor Recognition of Emotional Facial Expressions (Cook et al., 2013) But given that alexithymia occurs so often in the autistic population, I would argue it can still contribute significantly to an autism diagnosis.

Do you want to know if you have alexithymia?

Take the Online Alexithymia Questionnaire here:

Comments

Let us know what you think!