If you are autistic, you have probably heard of masking and/or camouflaging. In a broad sense, it’s the process of changing or concealing one’s natural personality in order to “fit in”, or perhaps more specifically in order to be perceived as neurotypical.

Although both these terms are often used interchangeably, research from the last few years has shown that there are a few distinct subcategories of camouflaging. Masking is only one of those subtypes, and arguably isn’t the most insidious of the three. So let’s explore camouflaging and autism.

Camouflaging

Camouflaging is of course a powerful evolutionary tactic used by many animals to disguise their appearance in order to avoid detection (called crypsis), or to imitate other animals so as to deter predators (called Batesian mimicry). Similarly, social camouflaging refers to strategies used to blend into our social surroundings, or present ourselves as different from who we are. Unlike physical camouflaging, however, it is not so much about being rendered completely invisible, but to camouflage behaviors that might make us stand out in some way. Camouflaging and mimicry is used to be seen in a way that is deemed appropriate by the group(s) we want to be included in.

Some extent of camouflaging is probably inherent to human interaction; we learn social skills to improve social interaction, we adhere to social conventions that may not make complete sense to us, and we adjust our behavior as the situation demands. For example, we tend to behave differently at work than at home. But for some people, the need to camouflage is a lot less superficial. Of course, the need to camouflage is proportional to how strange your behavior is perceived to be by your surroundings. And since autism is generally not very well understood by non-professionals—and even many professionals, honestly—it is us autistic people who find we often have a greater need to camouflage.

For other people camouflaging might mean acting, talking, and/or dressing a certain way in order to fit in with a social group of their preference. And while this probably pertains to autistic people as well, our need to camouflage tends to go deeper; because autistic people often have to camouflage their autistic behaviors, so as to minimize the visibility of one’s autism in social situations.[1]Development and Validation of the Camouflaging Autistic Traits Questionnaire (CAT-Q) (Hull et al., 2018)

Autistic people also show a fear response to calm chemicals,[2]Autism and the smell of fear | ScienceDaily[3]Altered responses to social chemosignals in autism spectrum disorder (Endevelt-Shapira et al., 2017) so whereas social situations may be fun for some, for autistic people anxiety is likely to come up more readily, either from social interactions with people you don’t know, or an environment that provides a high level of sensory stimulation. As a result, one might seclude oneself more, or stay with the social situations and in all likelihood camouflage more. Either strategy has its consequences; camouflaging is using strategies to fight against potential ostracization,* while avoiding social situations may be an act of self-ostracization.† I will explain later in this post what the (potential) consequences of maintaining this fight are.

- The social psychologist Kipling Williams—who has written extensively on ostracism as a modern phenomenon—defines ostracism as “any act or acts of ignoring and excluding of an individual or groups by an individual or a group.”[4]Ostracism: The Power of Silence | Kipling D. Williams

- Self-ostracization is any act performed by oneself—either inadvertently or with intent—that leads to being excluded from other people or groups.

To read more about a fear response to calm chemicals, have a look at:

A fear response to smelling calm chemicals

Reasons for camouflaging

In 2019, Eilidh Cage and Zoe Troxell-Whitman published a study that looked into the reasons autistic adults have for camouflaging. In the table below you can see various reasons for camouflaging, and loading scores, which give a measure of how significant that item is as a reason for camouflaging in autistic adults.[5]Understanding the Reasons, Contexts and Costs of Camouflaging for Autistic Adults (Cage & Troxell-Whitman, 2019)

Conventional reasons

Relational reasons

But I think more telling were the participants’ responses when they were asked what other factors cause them to camouflage. They followed 5 major themes:[6]Understanding the Reasons, Contexts and Costs of Camouflaging for Autistic Adults (Cage & Troxell-Whitman, 2019)

Other reasons

Camouflaging subtypes

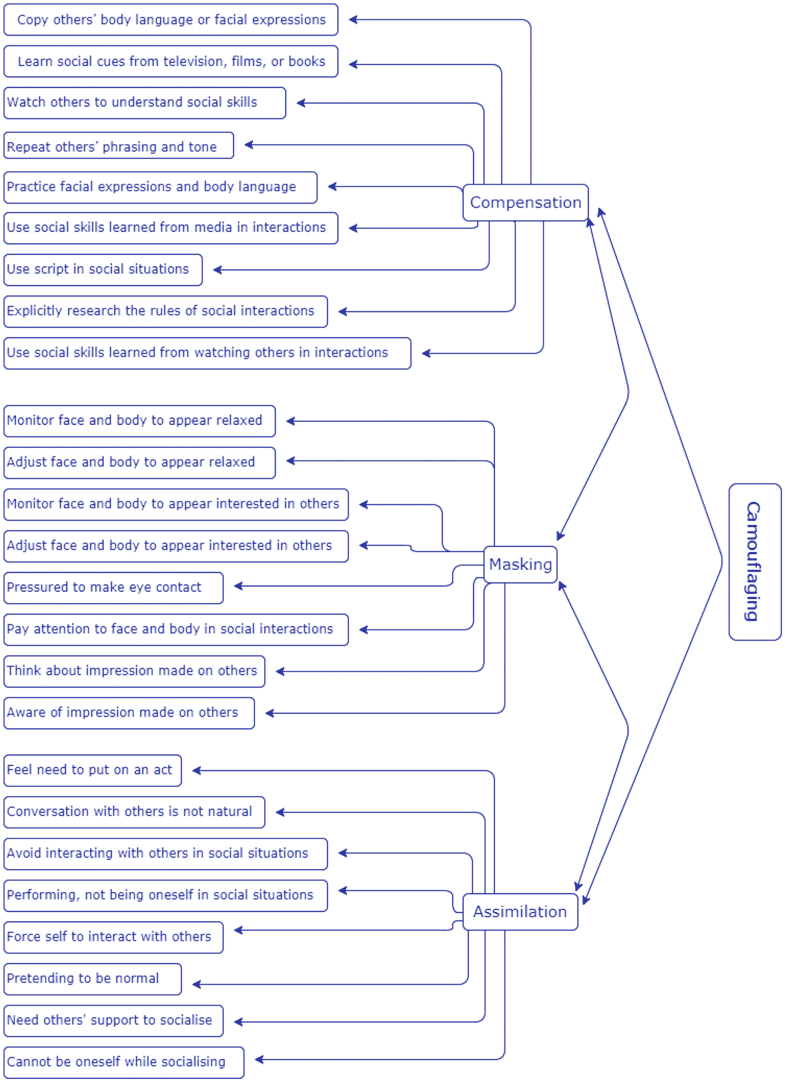

Based on research from 2018 by Laura Hull et al., the following 3 subcategories of camouflaging were defined:[7]Development and Validation of the Camouflaging Autistic Traits Questionnaire (CAT-Q) (Hull et al., 2018)

- Compensation — Strategies used to actively compensate for difficulties in social situations.

- Examples: copying body language and facial expressions, learning social cues from movies and books (see Autism & movie talk).

- Masking — Strategies used to hide autistic characteristics or portray a non-autistic persona.

- Examples: adjusting face and body to appear confident and/or relaxed, forcing eye contact.

- Assimilation — Strategies used to try to fit in with others in social situations.

- Examples: Putting on an act, avoiding or forcing interactions with others.

In the diagram below, you can see all 25 items of the social camouflaging model; 9 for compensation, 8 for masking, and 9 for assimilation.

Based on the social camouflaging model, the Camouflaging Autistic Traits Questionnaire (CAT-Q) was developed.[8]Development and Validation of the Camouflaging Autistic Traits Questionnaire (CAT-Q) (Hull et al., 2018) For more information on the validity of the model, how autistics and neurotypicals score on the CAT-Q, or if you want to take the test yourself, have a look at the following post:

The CAT-Q

Consequences of camouflaging

Research from 2017 by Laura Hull et al. indicates that motivations for camouflaging include fitting in and increasing connections with others.[9]“Putting on My Best Normal”: Social Camouflaging in Adults with Autism Spectrum Conditions (Hull et al., 2017) The short- and long-term consequences of camouflaging, they show, include exhaustion, challenging stereotypes, and threats to self-perception. So it’s interesting that the very attempt to increase connections with others by means of masking leads to a disconnected or distorted self.[10]“Putting on My Best Normal”: Social Camouflaging in Adults with Autism Spectrum Conditions (Hull et al., 2017)

Here is a list of the consequences of camouflaging as reported by various studies, as well as autistic people themselves:

- Autistic people describe camouflaging as both physically and mentally exhausting.[11]“Putting on My Best Normal”: Social Camouflaging in Adults with Autism Spectrum Conditions (Hull et al., 2017)

- Autistic people report feeling anxious and stressed after camouflaging, and as though they were not being their ‘true selves’.[12]“Putting on My Best Normal”: Social Camouflaging in Adults with Autism Spectrum Conditions (Hull et al., 2017)

- Late-diagnosed autistic women also reported experiencing exhaustion after camouflaging, and felt it negatively impacted their identity.[13]The Experiences of Late-diagnosed Women with Autism Spectrum Conditions: An Investigation of the Female Autism Phenotype (Bargiela, Steward & Mandy, 2017)

- Autistic people who reported camouflaging showed greater symptoms of depression, and felt less accepted by others.[14]Experiences of Autism Acceptance and Mental Health in Autistic Adults (Cage et al., 2018)

- Camouflaging has also been found to be a risk marker for suicidality in autistic adults.[15]Risk markers for suicidality in autistic adults (Cassidy et al., 2018)

Research from 2020 by Jonathan Beck et al. also showed that for women who reported above-average levels of camouflaging:[16]Looking good but feeling bad: “Camouflaging” behaviors and mental health in women with autistic traits (Beck et al., 2020)

- Camouflaging was associated with having thoughts about suicide and struggling to function in everyday life.

- Trying to camouflage autistic traits was associated with mental health challenges, regardless of whether those traits were very mild or more severe.

I also wrote a more narrative-driven article on the consequences of masking, which you can read here:

Masking: is it good or bad?

Consequences by subtype

Now that I’ve covered both the subcategories of camouflaging and the consequences, I want to talk a bit more about the consequences of the subcategories. People often stress the consequences of masking, but if I look at the items of the social camouflaging model above, masking doesn’t seem to be the most insidious. Whether by design or happenstance, the subcategories actually seem to be listed in order of least to most harmful to the self. Here is my assessment of the three subcategories:

Compensation

Compensation is basically the acquisition and application of social skills through internalizing scripts. I would say this is nothing more than learning and using social skills. However, it’s compensating in that it’s an effort to internalize social rules that aren’t intuitive to us. Since it takes a deliberate effort to respond appropriately in social settings, it can be immensely exhausting to participate. Compensation probably doesn’t go directly at the expense of the self. Yet the draining nature of this process can still impact our mental health.

Speaking for myself, back when I worked at a design studio, at the end of the day I would come home absolutely exhausted; I would rest for two hours, then do some grocery shopping, and then eat and rest some more. And it’s not that I act like a social butterfly at work. I get completely drained just being around my colleagues, trying to anticipate what they say and respond appropriately, and have the occasional social exchange during lunch. On Fridays, my bosses and colleagues would stop working early and go outside to enjoy a beer together. I would always stay in the studio and continue working. My bosses were puzzled by that. Why wouldn’t I join them and be social? I wouldn’t because it takes too much out of me to stand there and think of things to say. Besides, I don’t like beer. I got a lot more satisfaction out of getting some work done than out of socializing with my colleagues.

By compensating less, I get drained less. But as a consequence, it’s a lot harder for me to develop emotional relationships with colleagues, classmates, etc. And looking at the group dynamics, I noticed that made a difference. My colleagues and bosses liked me, but since I was less approachable to them, I would be included less in discussions, jokes, and probably even projects and job opportunities.

Masking

Masking is the active suppression of the telltale signs of anxiety and (other) autistic features in order to maintain the appearance of confidence and social prowess. If you look at the individual items of masking listed in the social camouflaging model, they don’t seem that insidious. For example, monitoring your face and body to appear interested in others is something presumably most people do. But what if your face looks naturally uninterested, so your neutral look often causes awkward situations or even ends up hurting people? What if your tendency to look away from other people’s eyes is perceived as you showing deception or a lack of confidence?

Yes, we all regulate our responses to each other. But while a lot of our social behaviors are intuitively understood by others, people aren’t trained to understand autistic social behaviors. Since our autonomic responses can deviate from what people expect, autistic people are often confronted with the choice to inhibit their intuitive responses, and express themselves in ways we’ve learned other people have come to expect. As you can imagine, this is even more draining to maintain. And it’s a lot less superficial than compensation. Compensation is trying to keep up with others socially. But masking is hiding aspects of ourselves in order to fit in, or simply to make social interactions go smoothly. If we don’t mask, we risk being excluded.

For me, masking is too much. If I focus too much on assessing the emotional states of others, anticipating them, and responding in a way they appreciate or expect, I have less brainpower to dedicate to the content of what I want to share. But as a consequence, people would find me unapproachable, and I would be left out of many things. I particularly noticed this at the art academy. When it came to projects where we had to form groups to work together, I was generally one of the few people that found no people to work with. Oh there were plenty of people I would love to have grouped with, but they already grouped with other people. Yet people did come to me for ideas, so it’s not that people didn’t want to work with me because I lacked talent. I noticed a big difference in our motivations for working with others; I wanted to work with people that had great ideas and knew how to execute them, while my classmates seemed largely driven by social factors. They wanted to work with people they clicked with.

If you mask less, as an autistic person you might find people click with you less, which can have a lot of consequences for personal relationships, your career, and more. But if you mask more, you may start feeling like you have to alter who you really are for people to like engaging with you.

Assimilation

Assimilation is all about trying to fit in. This is masking on a much deeper level, as it’s no longer about covering up some proclivities, but about presenting as someone you are not, so as to avoid being excluded. In assimilation, you have to force yourself to engage socially, or avoid it altogether. To the extent you do force yourself to engage, you basically have to put up a performance. Some autistic women reported they consciously “cloned” themselves based on a popular girl in their class whilst at school, and would imitate their conversational style, intonation, movements, dress-style, interests, and other mannerisms, in minute detail.[17]A Behavioral Comparison of Male and Female Adults with High Functioning Autism Spectrum Conditions (Lai et al., 2011)

Personally, I have little experience with this, simply because it’s way too draining and difficult for me to do and maintain. But a very distinct risk of assimilation is also that you can lose sight of who you are. As I wrote in Masking: is it good or bad?, the more you present yourself as someone else, the less time you spend being who you actually are, resulting in the gradual diminishment of the self. This will have a major impact on both your sense of self and your mental health in general. Research from 2020 by Sarah Cassidy et al. indicated that assimilation, in particular, is significantly correlated with suicidal thoughts and behaviors.[18]Is Camouflaging Autistic Traits Associated with Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviours? Expanding the Interpersonal Psychological Theory of Suicide in an Undergraduate Student Sample (Cassidy et al., 2020) So when people talk about the dangers of masking, they are most likely describing assimilation in particular.

Camouflaging is a common social strategy in autism. Some of it is part of social skills, but a substantial part of camouflaging negatively impacts autistic people’s wellbeing, either because it constantly drains them, or because it actively eats at their soul. And while you may hear a lot about masking, interestingly but also worryingly, autistic people actually score highest on assimilation—the most insidious aspect of camouflaging.

For more information on how autistic people and neurotypicals score on camouflaging, or if you want to find out how you score, have a look at the post below.

Comments

Let us know what you think!